The state of financial knowledge in the European Union

Financial literacy is essential in modern economies, where saving and preparing for retirement has shifted increasingly to the individual.

Executive summary

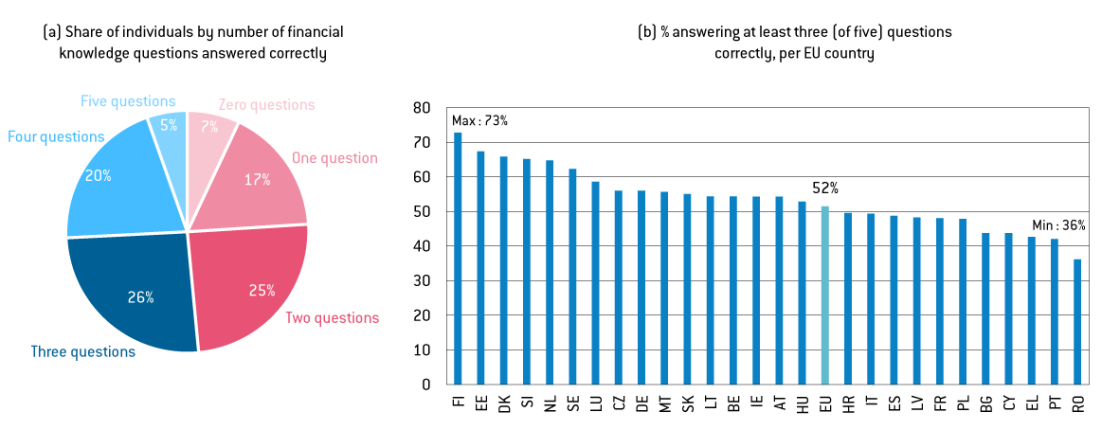

- Only one in two individuals in the European Union, on average, is financially knowledgeable. In response to a 2023 survey containing five questions assessing basic financial knowledge, only half of the respondents answered at least three of the five questions correctly. This represents a low level of financial knowledge and an obstacle for individuals to invest in financial markets.

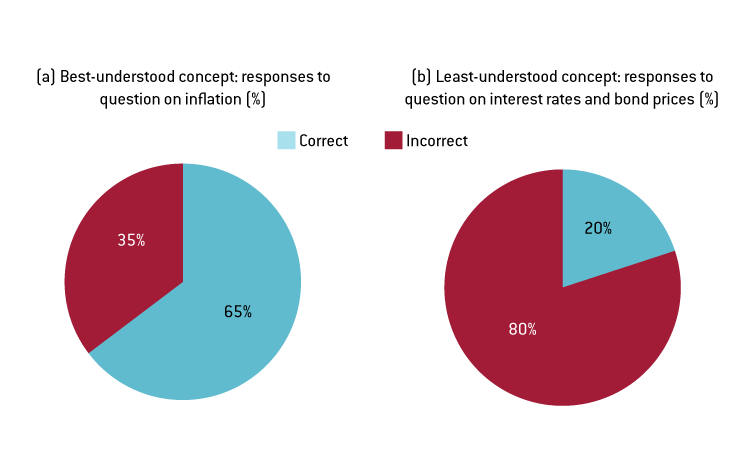

- The questions most often answered correctly by respondents measured understanding of inflation and the relationship between risk and return. By contrast, only one in five respondents answered a question on the relationship between interest rates and bond prices correctly.

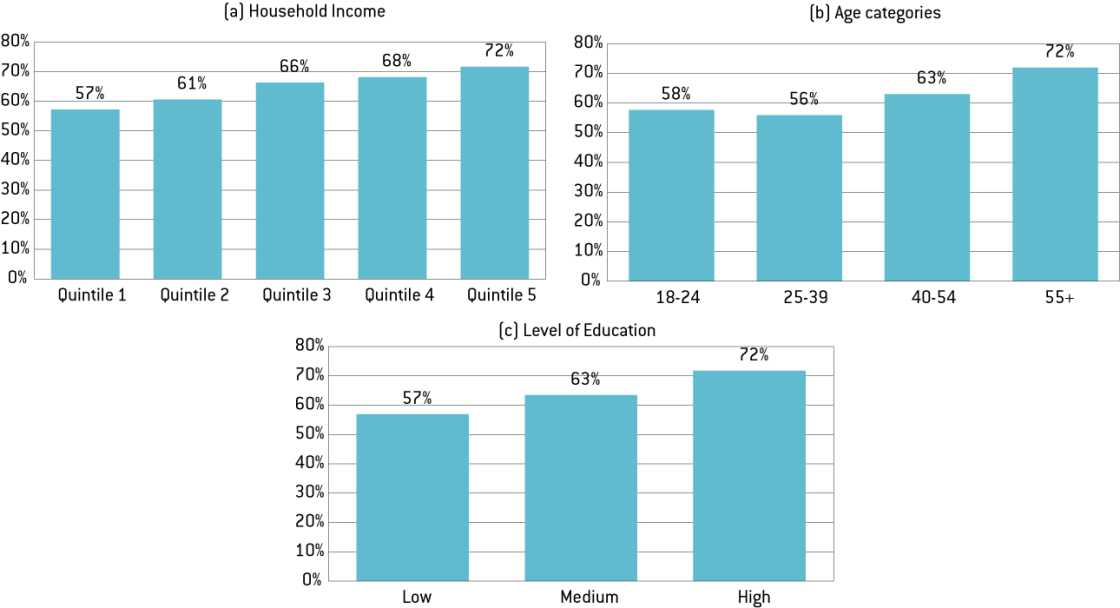

- Regarding inflation, there is a large difference between the least and most educated respondents in terms of answering the relevant question correctly. Gaps in understanding the concept of inflation are also evident between the youngest (18-24) and oldest respondents (55+) and between the poorest and richest households.

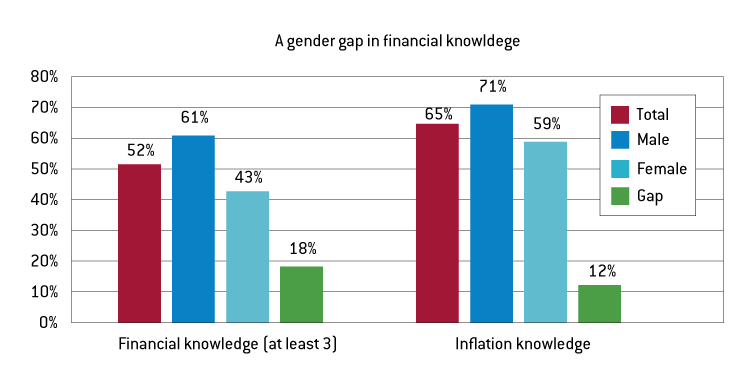

- A gender gap is present in financial knowledge, with 18 percentage points more men than women answering at least three out of five questions correctly, on average in the EU.

- Those with greater financial knowledge are less financially fragile in that they can still cover their expenses if there is a sudden loss of income, and are more confident that they will have sufficient funds to sustain themselves during retirement.

- Countries with higher proportions of people who are financially knowledgeable have higher numbers of people who both save with and borrow from financial institutions, an indication that financial knowledge may improve financial inclusion.

- All EU countries have, or are in the process of putting together, a national financial literacy strategy. There is an urgent need to roll out these strategies, to monitor progress over time and to establish best practices. Particular attention needs to be given to how financial knowledge interacts with digital skills as financial services are increasingly digitalised. Financial literacy strategies should also help close gender and other gaps in knowledge among vulnerable groups, and should ensure that financial education starts early and in schools.

Paper prepared at the request of the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the European Union for the informal Ecofin meeting on 23-24 February 2024.

1 Introduction

Interest in financial literacy stems from the question of whether households have enough knowledge and skills to manage their financial well-being. Financial knowledge is essential in modern economies in which the responsibility for saving and preparing for retirement has shifted increasingly to the individual. From pensions to mortgages, to new financial instruments, individuals must make decisions that are more complex and riskier than in the past. Meanwhile, the digitalisation of finance has made it easier to access financial products, exposing consumers to unknown and rapidly changing risks. Equally, climate change presents greater risks through, for example, floods and fires that require action at both the collective and individual level, not least in the form of insurance.

Measurement of financial literacy more than a decade ago showed low financial knowledge among a large share of the population, even in countries with well-developed financial markets, including European Union (EU) countries (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). Since then, however, interest in improving financial literacy has grown globally. In 2012, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)

1

See https://www.oecd.org/pisa/.

, which measures the state of skills young people need to succeed in the labour market, added financial literacy to the traditional set of skills it normally measures, deeming it essential for participating in economic activity. The PISA comprehensive definition of financial literacy has become a reference for measuring financial literacy, among both the young and the adult population:

"Financial literacy is knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, and the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life" (OECD, 2014).

Financial literacy refers not only to knowledge and understanding but also to the ability to promote effective financial decision-making. Academic efforts to understand the effects of financial literacy provide evidence that links financial knowledge to financial outcomes. Financially knowledgeable consumers are less financially fragile, in the sense that they cope better with unexpected financial shocks, are more likely to participate in stock markets, save more and plan better for their retirements, and are better at managing debt (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014, 2023).

In the EU, all member states have or are in the process of putting together a national financial literacy strategy. Such strategies typically aim to coordinate efforts to improve financial knowledge and influence education in school, and life-long financial education for the population and/or specific vulnerable groups (OECD, 2022).

The European Commission in 2023 carried out a survey to measure the level of financial knowledge in the EU as a whole and in all countries (European Commission, 2023a)

2

See also chapter three of European Commission (2023b) for a discussion of the results.

. The survey posed five questions to measure knowledge of inflation, compound interest, basic asset pricing, the relationship between risk and return, and risk diversification (see Appendix 1). We show that just over 50 percent of respondents, on average in the EU, could answer at least three of the five knowledge questions correctly. Thus, financial knowledge continues to be low, given that the questions measure basic financial concepts used in everyday financial decision-making. Of the five concepts, respondents understood the relationship between risk and return and inflation best, with about 65 percent answering the relevant questions correctly. But, focusing just on inflation, this also means that 35 percent of respondents do not understand that inflation decreases their purchasing power. With inflation having been unusually high since 2022, these results point to the difficulty of many households in adapting consumption and saving behaviour to such high price increases.

The Commission’s survey also asked questions on financial outcomes. We assess how financial knowledge measurement is linked to financial outcomes. The results broadly confirm the findings of many studies that show that resilience and confidence in having sufficient savings to live comfortably throughout the retirement years increase with greater financial knowledge.

We also show that EU countries with higher levels of financial knowledge have greater percentages of adults saving with and borrowing from financial institutions. Thus, greater financial knowledge is linked to greater financial inclusion.

2 Why is financial knowledge important? The evidence

An extensive literature on financial literacy has increased the understanding of who is more financially literate and how financial literacy can help improve financial decision-making. Perhaps unsurprisingly, financial literacy increases with GDP per capita and with education levels. We also know that financial literacy increases with age (but in several countries, it decreases later in the lifecycle) and that men are more financially literate than women (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014, 2023; Klapper and Lusardi, 2020).

The literature has also made progress in establishing a causal effect between financial knowledge (and financial education) and outcomes (Kaiser et al, 2022). Also, if financial knowledge is pivotal in helping individuals build financial cushions, then high levels of financial knowledge at a country level can contribute to macroeconomic stability. The opposite should also hold: low levels of financial knowledge can contribute to vulnerabilities that pose risks to an economy’s stability (Batsaikhan and Demertzis, 2018). The causal link between financial literacy and the macroeconomy is less well-researched than the link with outcomes at the household level, but we expect it to be as relevant for a country’s overall economic stability.

Existing measures of financial knowledge, including those we consider in this paper, have focused on fundamental topics that are applicable to all countries and are at the basis of financial decision-making. These include the time value of money (compound interest), the real value of money (inflation), the link between interest rates and bond prices (basic asset pricing), the relationship between risk and return, and the workings of risk diversification (both fundament concepts at the basis of investing).

A better understanding of these concepts is associated with better management of both the asset and liability side of a household’s balance sheet. Households with greater financial knowledge have been shown to:

Allocate lifetime resources better. Greater financial knowledge leads to lower financial fragility, ie the ability to deal with unexpected expenses. Greater knowledge is also linked to higher wealth accumulation. For example, German households with lower levels of financial literacy, which were badly affected during the financial crisis, were more likely to sell their assets at a loss (Bucher-Koenen and Ziegelmeyer, 2011). More financially literate households earn greater returns on their investments (Deuflhard et al, 2015; Clark et al, 2017) and pay lower fees on their mutual fund holdings (Hastings et al, 2011). These effects are consequential: about 30 percent to 40 percent of wealth inequality close to retirement is accounted for by variations in financial knowledge (Lusardi et al, 2017).

Plan better for retirement. Poor financial knowledge prevents people from preparing for the future. Those with low levels of financial knowledge are less likely to plan for retirement. This outcome is notably consistent across countries (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011; 2014). As societies age and people live longer post-employment, having sufficient means will be crucial for household financial stability and for the sustainability of publicly funded pension schemes.

Be more likely to participate in financial markets. As people acquire greater financial knowledge, they are more likely to participate in financial markets, by investing in stocks, for example. Evidence from Dutch households showed a strong effect of knowledge on stock market participation (Van Rooij et al, 2011). This is of great relevance for the EU, which aims to increase participation by retail investors and the availability of market-based funding for firms via the capital markets union project and the European Commission’s May 2023 Retail Investment Package proposals

3

See European Commission press release of 24 May 2023, ‘Capital Markets Union: Commission proposes new rules to protect and empower retail investors in the EU’, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_2868.

. This will help firms to grow and also to make financing available for the green and digital transitions.

There is also some evidence of the effects of financial knowledge on managing the liability side of the balance sheet:

Contain over-indebtedness. People with low levels of financial knowledge tend to borrow at more expensive terms (Lusardi and Tufano, 2015). This is particularly true for young people (OECD, 2005). In the era of digitisation, ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL) schemes have reduced the threshold of access to credit significantly, as no credit checks are done prior to use. We still have no evidence on how financial knowledge affects the use of BNPL schemes, but significant distress has been reported

4

Maria Demertzis, ‘Buy now, pay later: the age of digital credit’, Opinion, 17 May 2022 , Bruegel, https://www.bruegel.org/comment/buy-now-pay-later-age-digital-credit.

in terms of both overspending and struggling to repay debts. We also know that such schemes are more popular with the young, who are typically less financially knowledgeable.

There are two further issues that underline the relevance of financial knowledge for financial decision-making.

Digital finance needs more financial knowledge. More and more financial services are available in digital form. Recent efforts to measure financial literacy also attempt to understand how it interacts with digital skills and digital access to finance. However, the range of digital products and services is wide, and therefore, their degree of simplicity/complexity varies. This, in turn, implies that the threshold for using such products changes depending on their complexity, and their relationship with financial knowledge is also complex.

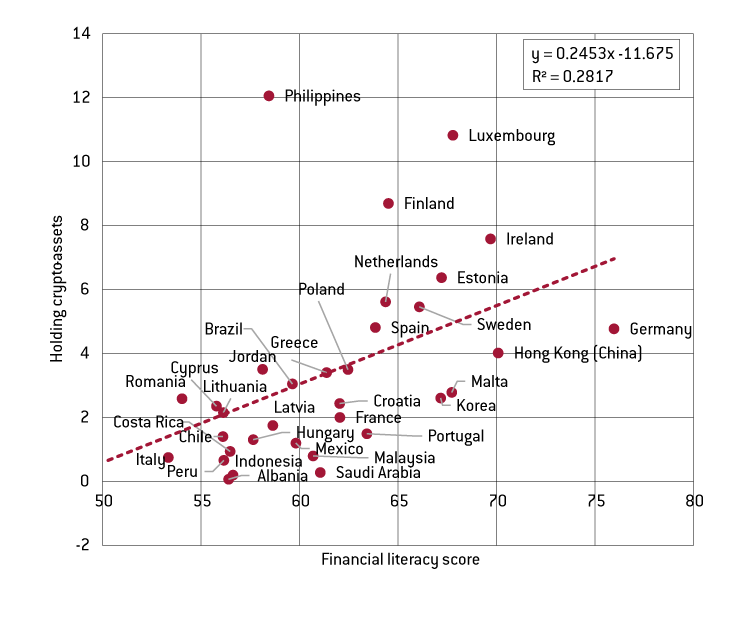

For example, evidence from US millennials (broadly, those born in the 1980s and up to the mid-1990s) shows that those who use mobile payments are also more likely to mismanage their funds or experience financial difficulties, and are less financially knowledgeable (de Bassa Scheresberg et al, 2020). When it comes to online banking, however, evidence from Cyprus shows that it is used by those with more financial knowledge (Anyfantaki and Andreou, 2022). Arguably, online banking incorporates layers of complexity to prevent mistakes and, therefore, requires greater financial knowledge. Similarly, preliminary evidence on holdings of crypto assets (effectively Bitcoin, which dominates the crypto market) shows that countries with higher levels of financial knowledge have more individuals holding crypto assets (Figure A2 in Appendix 2).

Financial knowledge increases trust in institutions. Lastly, there is a positive relationship between the level of financial knowledge and the degree of trust in institutions (van der Cruijsen et al, 2021). Evidence from the Netherlands shows that all levels of trust increase with greater financial knowledge. This refers to trust in the institutions people use, such as their own bank, and in the whole financial sector (banks, pension funds and insurance companies). Also, the evidence shows that financial regulators also benefit from increased trust in jurisdictions with higher levels of financial knowledge.

3 The state of financial knowledge in the EU

The European Commission, in its survey measuring financial literacy across the EU (European Commission, 2023a), followed the OECD’s definition, according to which financial literacy is a combination of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour. In line with the academic literature, we report the findings on financial knowledge only and examine separately how this is linked to financial behaviour

5

Both the OECD (2023) and European Commission (2023) metrics of financial literacy include measures of financial knowledge and behaviour. In this paper, we use only the financial knowledge component to measure financial literacy and then examine how knowledge affects behaviour. This aligns with how academic research uses survey data on financial literacy.

.

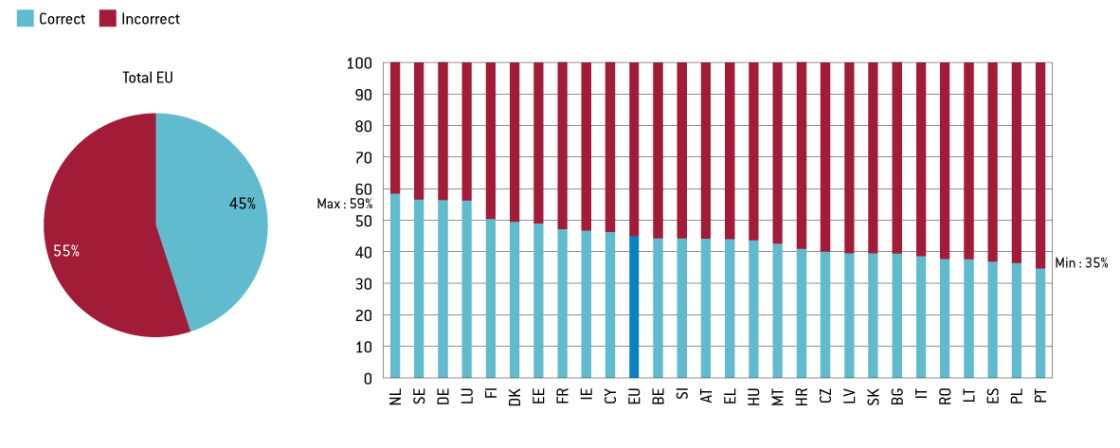

The European Commission survey (2023a) measured knowledge of the following five concepts: compound interest, inflation, the effects of interest rates on bond prices, risk versus return, and risk diversification. We assume that consumers are financially knowledgeable if they answer at least three (of the five) questions correctly. This threshold is consistent with other work measuring financial knowledge across countries (Klapper and Lusardi, 2020).

Based on this definition, 52 percent of respondents on average in the EU are financially knowledgeable, with the lowest level being 36 percent and the highest 73 percent (Figure 1b). This is a worrying finding as the threshold for being financially knowledgeable is low (ie a minimum of three out of five questions answered correctly), and the survey measures understanding of fundamental concepts that are of relevance in daily financial decision-making. Figure 1a shows shares of respondents, on average in the EU, by how many questions they answered correctly out of the five asked (scored from zero to five). The sum of the numbers in the blue slices is the share of respondents who answered at least three questions correctly.

Figure 1: Financial knowledge in the EU

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a). Notes: The measure of financial knowledge is based on five questions. Individuals are financially knowledgeable if they answer at least three questions correctly.

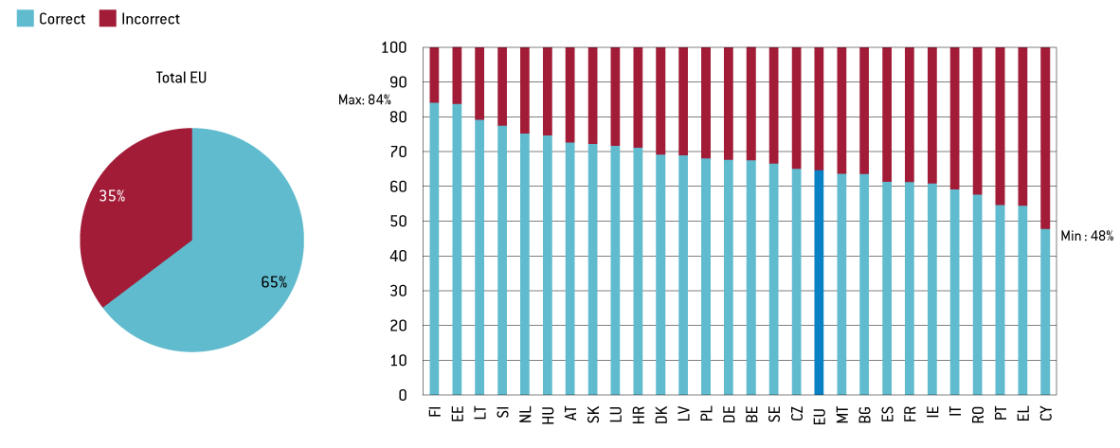

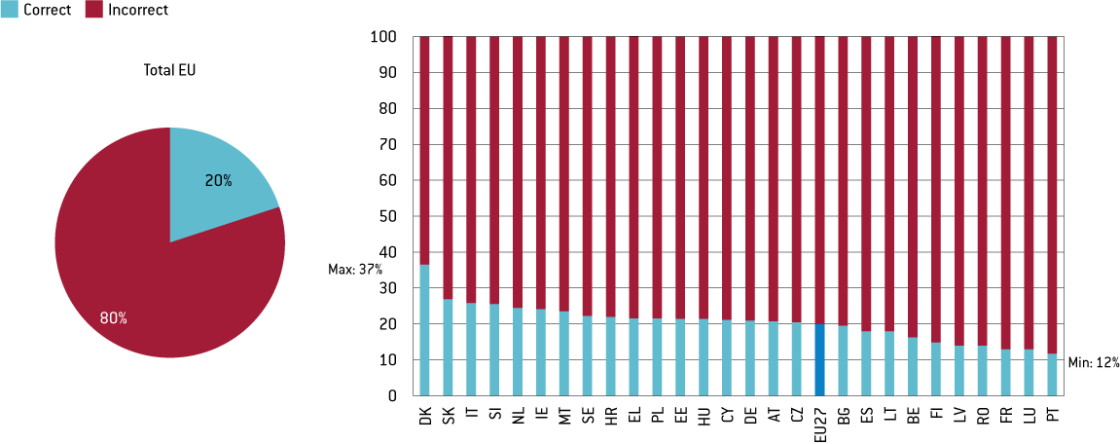

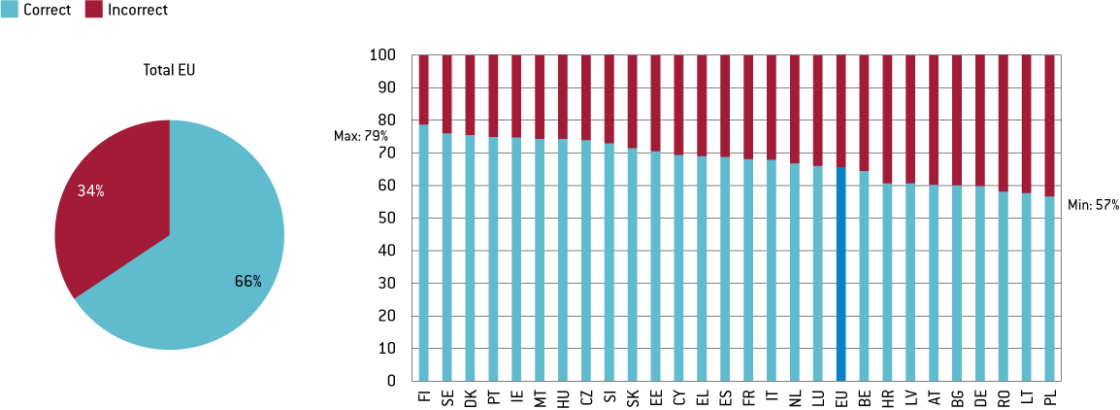

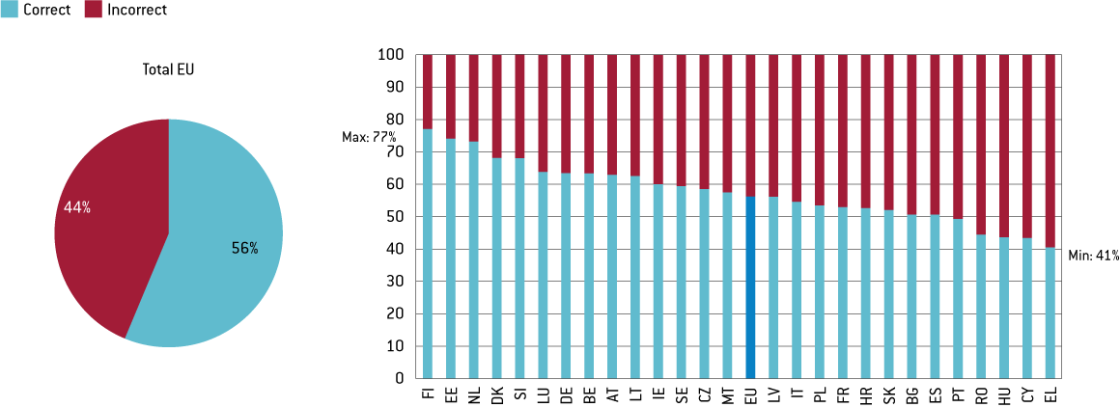

In Appendix 1, we also summarise the results for all five questions. Figure 2 shows the results for the concepts respondents understood most and least. The inflation question (and the risk-return question) was answered correctly by about 65 percent of the EU population (Figure 2a). However, the great majority of respondents showed little understanding of the relationship between interest rates and bond prices (Figure 2b): only 20 percent answered this question correctly. This is a question that enables a distinction to be made between little and advanced financial knowledge.

Figure 2: Best-understood (inflation) and least-understood (link between interest rates and bond prices) concepts: % of correct/incorrect answers, EU

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a), Questions Q3 and Q4.

Given the high levels of inflation in all EU countries, and its disproportionate impact on the poor (Claeys et al, 2024), it is significant that as much as 35 percent of people on average in the EU do not know how the level of inflation affects their purchasing power. Figure 3 reports the understanding of inflation among different demographic groups. There is a 15 percentage-point gap in the understanding of inflation between the lowest and highest household income brackets. There are similar gaps across age and education: there is a 14 percentage-point gap between the youngest and the oldest respondents and a 15 percentage-point difference between those with the lowest and highest education levels.

Figure 3: Inflation knowledge of different groups, EU, % of respondents answering correctly

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a), Analysis of the inflation question (Q3). Notes: Levels of education are defined as follows: low is defined as including up until lower secondary education. Medium is defined as including from upper secondary education up until post-secondary but non-tertiary education. High is defined as including tertiary education up until and including doctoral level (Source: International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) – Statistics Explained).

Figure 4 shows the differences in financial knowledge depending on gender, a well-documented finding in the literature. There is an 18 percentage-point gap in financial knowledge between men and women, according to the responses in the European Commission survey (2023a). This is in line with what other studies have found (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014, 2023; Klapper and Lusardi, 2020). Women are always more likely (and up to twice as likely, depending on the question) to answer ‘I do not know’ to the financial knowledge questions. Previous studies have shown that by removing this option, the gender gap can be reduced by as much as a third (Bucher-Koenen et al, 2021). Regarding the inflation question, the gender gap is 12 percentage points.

Figure 4: The gender gap in financial knowledge in the EU (%)

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a). Notes: Financial knowledge corresponds to the share of respondents who answered more than three (out of five) questions correctly.

4 How does financial knowledge affect financial outcomes?

4.1 The evidence from the European Commission survey

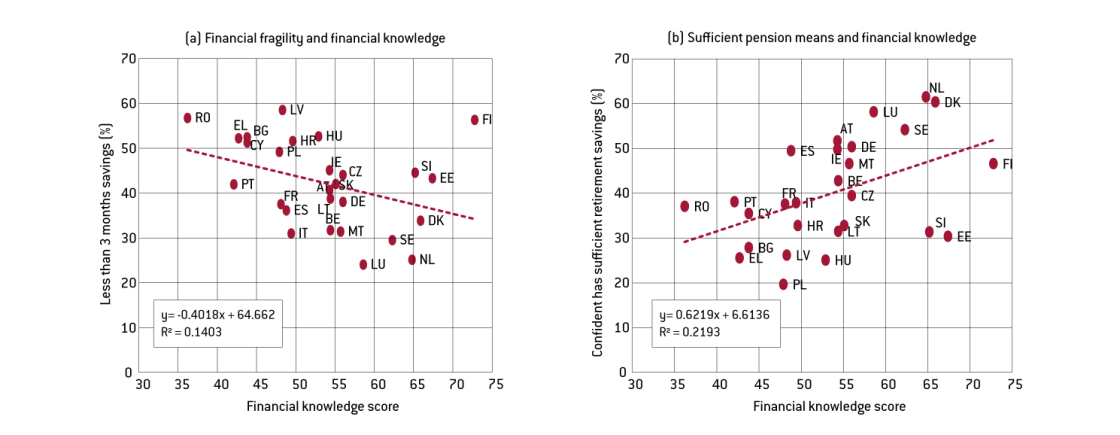

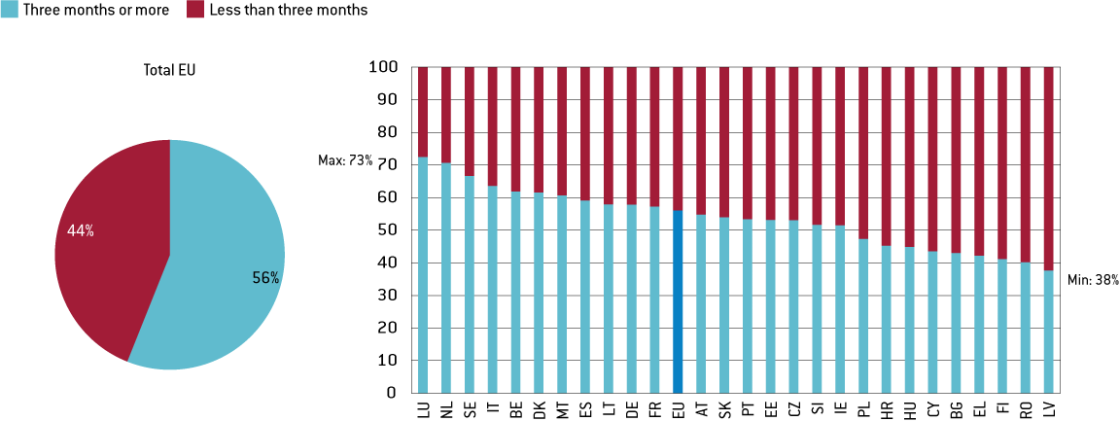

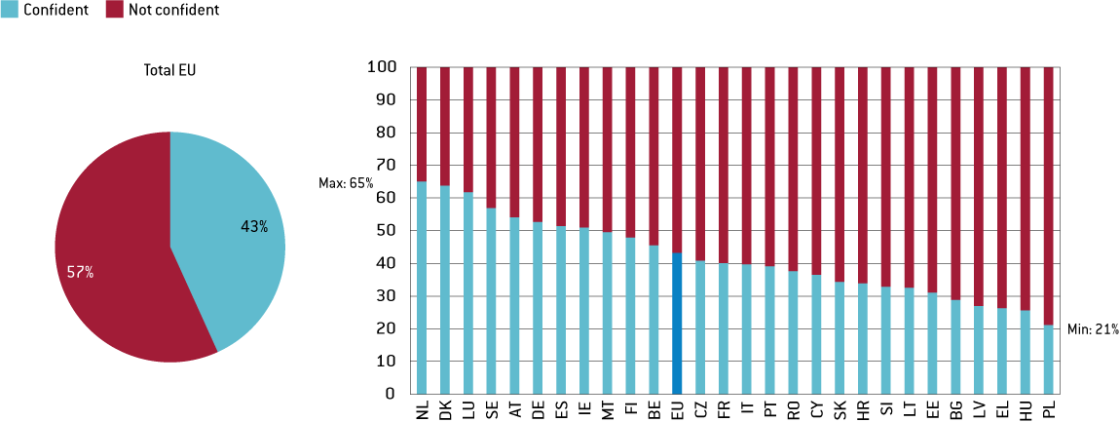

The European Commission (2023a) survey also asked consumers questions pertaining to financial resilience in both the short and long terms. We report how financial knowledge is linked to both financial fragility and pension security across countries. Appendix 3 summarises the questions and the detailed results. Figure 5(a) shows a negative association between financial knowledge and financial fragility, ie the less financially knowledgeable are less likely to have adequate resources to deal with an unexpected loss of income without having to borrow.

Figure 5: Financial knowledge, financial fragility and pension security

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a). Notes: Sufficient financial knowledge (at least three out of five questions answered correctly) is correlated with (a) the % of respondents who self-report having savings of less than three months’ worth of income to cover living expenses if the main source of income was lost today; (b) the % of respondents who self-report their degree of confidence that they have enough money to live comfortably through their retirement years (sum of ‘very confident’ and ‘somewhat confident’).

The data shows that a 10 percentage points higher level of financial knowledge is associated with a 4 percentage points lower number of people reporting insufficient means to cover their living expenses following an unexpected loss of income (see also Demertzis et al, 2020).

Similarly, Figure 5(b) shows that greater financial knowledge is associated with greater confidence in having sufficient financial means for retirement. A 10 percentage point higher level of financial knowledge is associated with a 6 percentage point higher number of people who report having sufficient means for retirement.

4.2 The contribution of financial knowledge to financial inclusion

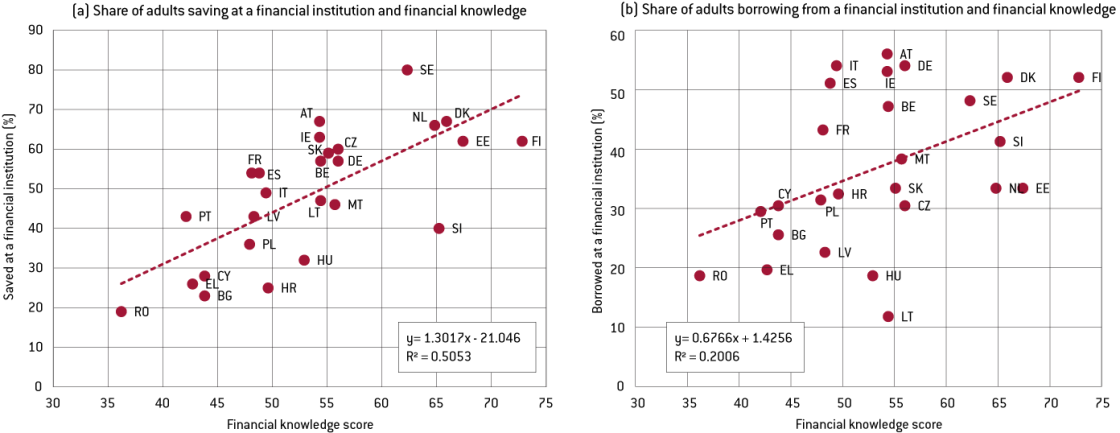

We next ask how financial knowledge might be associated with measures of financial inclusion (Batsaikhana and Demertzis, 2018; Lusardi and Messy, 2023).

We use two variables from the World Bank Global Findex database on the percentage of respondents who report saving with or borrowing from a financial institution (see Appendix 4 for more detail). Figure 6 shows the relationship between financial knowledge (as measured by European Commission, 2023a) and the number of adults that (a) save with and (b) borrow from a financial institution. A 10 percentage point higher level of financial knowledge is associated with 13 percentage points more adults saving with, and almost 7 percentage points more adults borrowing from, a financial institution.

Figure 6: Financial knowledge and share of adults who save with and borrow from a financial institution

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a) and World Bank Global Findex Database (2021). Notes: See Appendix 4 for the exact parameters used by the World Bank to determine the proportion of people borrowing and saving. The Findex database does not contain data for the saving and borrowing questions for Luxembourg in 2021.

The relationship between savings and financial knowledge is well established in the literature and our numbers confirm that. The relationship between borrowing behaviour and financial knowledge is less well-established. Our results are not definitive ,but they show that countries with more financially knowledgeable populations also have more people who borrow from financial institutions. Both these results suggest a link between financial knowledge and financial inclusion.

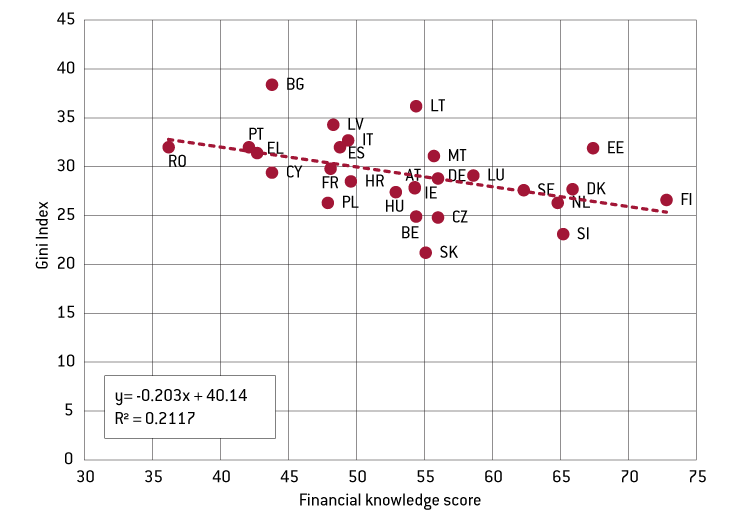

Figure 7 reports the association between financial knowledge (as measured by European Commission, 2023a) and income inequality (from Eurostat). The figure shows a negative relationship between financial knowledge and inequality as captured by the Gini index. In the EU, a 10 percentage point higher level of financial knowledge is associated with a smaller Gini index by over two percentage points.

Figure 7: Financial knowledge and inequality

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2023a) and Eurostat. The Gini Index for EU countries and Albania is from Eurostat’s ilc_di12 dataset (Gini index of equivalised disposable income) for 2022.

5 Discussion and policy recommendations

Financial knowledge in the EU is, on average, low. Approximately one in two people on average in the EU answer at least three out of five financial literacy questions correctly. Even for inflation, more than one in three people in the EU do not understand how inflation erodes their purchasing power. These are basic concepts that all consumers face daily, which, if not understood well, can lead to poor financial decisions. Given these low levels of financial knowledge, it is important to promote financial education programmes for both the young and the old across the EU.

Greater financial literacy will help advance the EU capital markets union agenda. Part of the EU’s capital markets union agenda is to stimulate consumers to invest responsibly and to make better use of existing investment opportunities. This requires a better understanding of concepts related to saving and investing. Without sufficient understanding of these concepts, it will be difficult and potentially damaging for consumers to participate in financial markets. While regulation can protect consumers from certain pitfalls, it will not replace the need to understand the risks involved. Given its economic relevance, financial literacy can be considered a complement to financial regulation.

There is a lack of systematic monitoring of progress on financial literacy progress. There are many efforts at the country level to measure financial knowledge and understand its effects on behaviour and attitudes. The European Commission survey done in the spring of 2023 (European Commission, 2023a) was the first survey to provide comparable data on financial literacy levels for all EU countries. It provides a benchmark for monitoring financial knowledge in the EU in a consistent way. We strongly recommend continuing this exercise to assess progress over time and add these statistics to the set of data that policymakers monitor regularly. This should help identify what constitutes best practices and permit the exchange of ideas and experiences, including for new topics (for example digitalisation but increasingly also ethical or sustainable investing).

All national financial literacy strategies must be rolled out and with adequate financial support. All EU countries either have or are in the process of designing national financial literacy strategies, often with the technical assistance of the OECD. As national strategies continue to be rolled out, further progress will be made in both literacy and financial outcomes, especially if adequate financial resources are put in place. Progress should be monitored, and best practices identified as countries proceed with full implementation.

The process of digitalisation increases the urgency for more financial knowledge. Attempts to advance the level of financial literacy in the EU should pay particular attention to how the digitalisation of finance interacts with financial knowledge, especially across different age groups. Care should be given to the identification of how different digital financial products or services affect behaviour, and what types of financial knowledge they require.

Accelerate efforts to advance levels of financial literacy, particularly for women and the young. Women’s financial literacy levels are lagging. This makes women particularly vulnerable to financial fragility and the risk of poverty throughout their lives and especially in retirement. However, studies show that while women’s levels of financial literacy are lower, they also respond better than men to efforts to educate and train them. Similarly, financial education must start early in life and help provide financial literacy skills to young adults. This is particularly important as the young have easier access to digital financial products much

earlier in life. It is very important to add financial literacy in schools, starting in elementary education and continuing in college, as well as throughout people’s lifetimes.

References

Anyfantaki, S. and P. Andreou (2022) ‘Financial Literacy and its Influence on Consumers’ Internet Banking Behaviour’, Bank of Greece Working Paper 275, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4197892#

Batsaikhan, U. and M. Demertzis (2018) ‘Financial Literacy and Inclusive Growth in the European Union’, Policy Contribution 08/2018, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/financial-literacy-and-inclusive-growth-european-union

Bucher-Koenen, T. and M. Ziegelmeyer (2011) ‘Who lost the most. Financial literacy, cognitive abilities, and the financial crisis’, ECB Working Paper 1299, European Central Bank

Bucher-Koenen, T., R. Alessie, A. Lusardi and M. van Rooij (2021) ‘Fearless woman: Financial literacy and stock market participation’, GFLEC Discussion Paper 21, available at https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Fearless-Woman-Research-March-2021.pdf

Claeys G., L. Guetta-Jeanrenaud, C. McCaffrey and L. Welslau (2024) ‘Inflation inequality in the European Union and its drivers, Bruegel Dataset, available at https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/inflation-inequality-european-union-and-its-drivers

Clark, R.L., A. Lusardi and O.S. Mitchell (2017) ‘Financial knowledge and 401(k) investment performance: A case study’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 16(3): 324-347

de Bassa Scheresberg, C., A. Hasler and A. Lusardi (2020) ‘Millennial Mobile Payment Users: A Look into their Personal Finances and Financial Behaviours’, ADBI Working Paper 1074, Asian Development Bank Institute, available at https://www.adb.org/publications/millennial-mobile-payment-users-personal-finances-financial-behavior

Demertzis, M., M. Domínguez-Jiménez and A. Lusardi (2020) ‘The financial fragility of European households in the time of COVID-19’, Policy Contribution 2020/15, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/financial-fragility-european-households-time-covid-19

Demertzis, M. and C. Martins (2023) ‘The value added of Central Bank Digital Currencies: a view from the euro area’, Policy Brief 13/2023, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/value-added-central-bank-digital-currencies-view-euro-area

Deuflhard, F., D. Georgarakos and R. Inderst (2019) ‘Financial literacy and savings account returns’, Journal of the European Economic Association 17(1): 131–164

European Commission (2023a) ‘Monitoring the level of financial literacy in the EU’, Flash Eurobarometer 525, available at https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2953

European Commission (2023b) 'European Financial Stability and Integration Review', chapter 3 in

Financial literacy in the EU: Trends, Relevance and Policy Contribution, available at https://finance.

ec.europa.eu/document/download/ffc80aa7-96a8-4500-b7a5-eaf1f8e607cf_en?filename=europeanfinancial-stability-and-integration-review-2023_en_0.pdf

Eurostat (2022) ‘Methodological Guidelines and Description of EU-SILC Target Variables’, 2022 Operation (Version 4), available at https://circabc.europa.eu/d/a/workspace/SpacesStore/94141a49-a4a7-48bc-89f7-df858c27d016/Methodological%20guidelines%202022%20operation%20v4.pdf

Hastings, J., O.S. Mitchell and E. Chyn (2011) ‘Fees, framing, and financial literacy in the choice of pension manager’, in O.S. Mitchell and A. Lusardi (eds) Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace, Oxford Academic Press

Kaiser, T., A. Lusardi, L. Menkhoffand C. Urban (2022) ‘Financial education affects financial knowledge and downstream behaviours’, Journal of Financial Economics 145(2): 255-272

Klapper, L. and A. Lusardi (2020) ‘Financial Literacy and Financial Resilience: Evidence from Around the World’, Financial Management 49(3): 589-614

Lusardi, A. and F.-A. Messy (2023) ‘The Importance of financial literacy and its impact on financial wellbeing’, Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing 1(1): 1-11

Lusardi, A. and O.S. Mitchell (2011) ‘Financial Literacy around the World: an Overview’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10(4): 497-508

Lusardi, A. and O.S. Mitchell (2014) ‘The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence’, Journal of Economic Literature 52(1): 5-44

Lusardi, A., P.-C. Michaud and O.S. Mitchell (2017) ‘Optimal Financial Knowledge and Wealth Inequality’, Journal of Political Economy 125(2): 431-744

Lusardi, A. and O.S. Mitchell (2023) ‘The Importance of Financial Literacy: Opening a New Field’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 37(4): 137-154

Lusardi, A. and P. Tufano (2015) ‘Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences and Over indebtedness’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 14(4): 332-368

OECD (2005) Improving Financial Literacy: Analysis of Issues and Policies, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

OECD (2014) PISA 2012 Results: Students and Money (Volume VI): Financial Literacy Skills for the 21st Century, PISA, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208094-en

OECD (2022) Evaluation of National Strategies for Financial Literacy, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/evaluation-of-national-strategies-for-financial-literacy.htm

OECD (2023) ‘OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy’, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers 39, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://doi.org/10.1787/56003a32-en

Van der Cruijsen, C., J. de Haan and R. Roerink (2021) ‘Financial knowledge and trust in financial institutions’, The Journal of Consumer Affairs 55(2): 680-714, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/joca.12363

Van Rooij, M., A. Lusardi and R. Alessie (2011) ‘Financial literacy and stock market participation’, Journal of Financial Economics 101(2): 449-472

Financial knowledge questions from the European Commission’s 2023 Flash Barometer 525 (European Commission, 2023), questions 2-6. All questions allow for the possibility of ‘I don’t know’, which is included as part of the incorrect answers in our calculations.

Financial knowledge questions: Q2- Q6

Q2 Financial knowledge: understanding of compound interest.

The question asked: Imagine that someone puts [€100] into a savings account with a guaranteed interest rate of 2% per year. They don’t make any further payments into this account, and they don’t withdraw any money. How much would be in the account at the end of five years?

Options: More than [€110] (correct answer); Exactly [€110]; Less than [€110]; Don’t know.

Q3 Financial knowledge: understanding of inflation.

The question asked: Now imagine the following situation. You are going to be given a gift of [€1,000] in one year and, over that year, inflation stays at 2%. In one year’s time, with the [€1,000], you will be able to buy:

Options: More than you could buy today; the same amount; less than you could buy today (correct answer); don’t know.

Q4 Financial knowledge: understanding of the relation between interest rates and bond prices.

The question asked: If interest rates rise, what will typically happen to bond prices?

Options: They will rise; they will fall (correct answer); they will stay the same, as there is no relationship between bond prices and the interest rate; don’t know.

Q5 Financial knowledge: understanding of risk and return.

The question asked: Which of the following is true? An investment with a higher return is likely to be:

Options: More risky than an investment with a lower return (correct answer); less risky than an investment with a lower return; as risky as an investment with a lower return; don’t know.

Q6 Financial knowledge: understanding of risk diversification.

The question asked: An investment in a wide range of ‘company shares’ is likely to be:

Options: More risky than an investment in a single share; less risky than an investment in a single share (correct answer); as risky as an investment in a single share; don’t know.

Appendix 2

Figure A2: Percentage of individuals who hold crypto assets and financial literacy scores

Source: Bruegel based on OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy. Underlying data can be found at https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/Financial Literacy Survey Adults_Annex D.xlsx. Notes: In computing these percentages, the values reported as ‘Do not know’, ‘Does not apply’ or ‘Refused’ were included in the denominator. Spain asked respondents about awareness and holding of crypto-currencies rather than crypto-assets. The samples from Jordan, Mexico and Saudi Arabia may not be representative of the entire adult population. The results for Malaysia and Spain are drawn from samples taken in 2021 using the 2018 Toolkit.

While Figure A2 shows that countries with higher financial literacy scores also have higher percentages of individuals who hold crypto assets, care must be exercised in generalising this result. We know that crypto assets, particularly Bitcoin, are popular in countries that do not have alternative digital payment systems. This is one of the arguments used by the central banks of those countries in advancing with the creation of central bank digital currencies (Demertzis and Martins, 2023). But these countries typically also have lower financial literacy scores.

Appendix 3: Financial outcomes

Financial outcomes questions from the European Commission’s 2023 Flash Barometer 525 (2023a), questions 8 and 10. All questions allow for the possibility of ‘I don’t know’, which is excluded from the calculations.

Q8 Having sufficient savings to meet an unexpected expense.

The question asked: If you lost your main source of income today, how long could you continue to cover your living expenses, without borrowing any money or moving house?

Options: I don’t have emergency savings; at least 1 week, but less than 1 month; at least 1 month, but less than 3 months; at least 3 months, but not 6 months; 6 months or more.

Notes: Definition of “Less than three months” includes those who have answered: 1) I don’t have emergency savings; 2) At least 1 week, but less than 1 month and 3) At least 1 month, but less than 3 months.

Q10 Confidence in having sufficient savings for retirement.

The question asked: Overall, how confident are you that you will have enough money to live comfortably throughout your retirement years?

Options: Very confident; somewhat confident; not too confident; not all confident; total confident.

Notes: Definition of ‘confident’ includes those who are very confident and somewhat confident.

Appendix 4: World Bank Findex data

Appendix C to the 2021 Global Findex contains a glossary, available at https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/22d13c2efe6497e6e105e3c396a97362-0050062022/original/Findex-2021-Glossary.pdf. This is a source of data on access to financial services globally and is based on country surveys in 123 economies.

Definitions for relevant questions:

- Borrowed from a formal financial institution (%): The percentage of respondents who report borrowing any money from a bank or another type of financial institution or using a credit card in the past year.

- Saved at a financial institution (%): The percentage of respondents who report saving or setting aside any money at a bank or another type of financial institution in the past year.