A sanctions counter measure: gas payments to Russia in rubles

A requirement for gas to be paid for in rubles is a way for Russia to side-step central bank sanctions.

A Greek language explainer based on this blog post was also published by Kathimerini. A Dutch version was published in Het Financieele Dagblad.

Russia’s Gazprombank has so far not been sanctioned by the European Union in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Gazprombank handles payments made by European gas importers, who would not be able to make euro (or dollar) payments for gas if it were sanctioned. The question however is whether the Russian state can access these payments made to Gazprombank and turn them into domestic currency to finance its current operations.

In a 31 March decree, Vladimir Putin ordered that gas exports to Europe should be paid for in rubles instead of euros or dollars. In practice, this means European gas importers should open both ruble and foreign currency accounts with Gazprombank and transfer dollars or euros to it. The proceeds would then be exchanged into rubles to pay for gas.

Why would Putin want to make these changes? A broad interpretation of EU sanctions on Russia’s central bank could provide an answer. If EU sanctions on the Bank of Russia are understood as covering all foreign assets in Russia’s possession, including proceeds from the sale of gas, and if these sanctions are enforced, the Russian state would not be able to access payments in euros (or dollars).

By contrast, the demand to pay in rubles can be constructed to bypass the euro or dollar financial system and therefore continue to feed Russia’s state finances. In the following, we describe what difference Putin’s decree potentially makes (see the appendix for details and which transactions would be blocked by sanctions).

Payments in euros

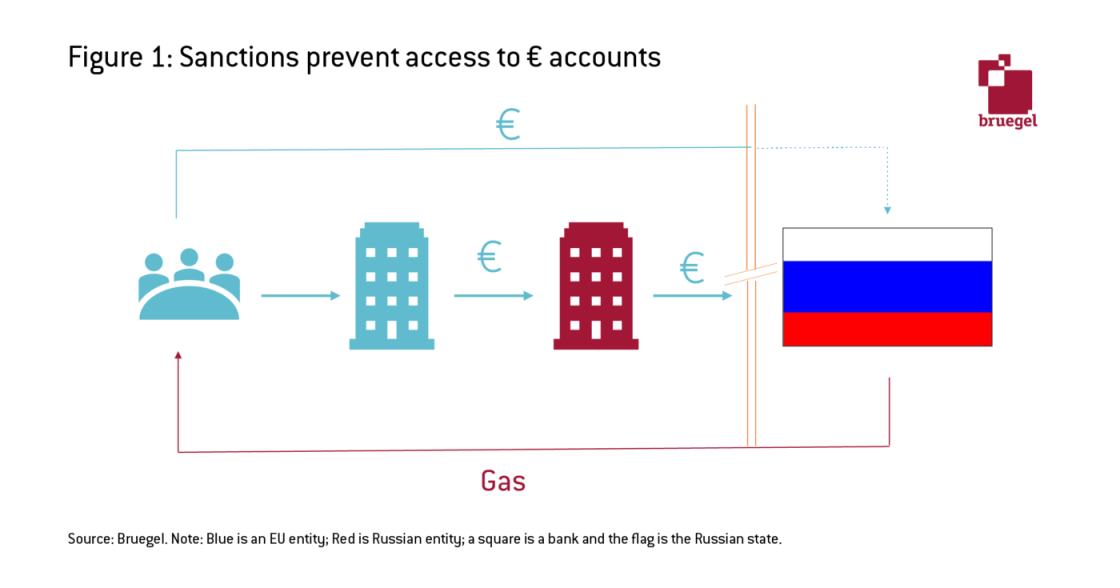

The gas importer pays euros from its own bank to Gazprombank. If the Russian state itself is sanctioned, it cannot access its foreign accounts and therefore the euros paid to Gazprombank remain frozen there (Figure 1).

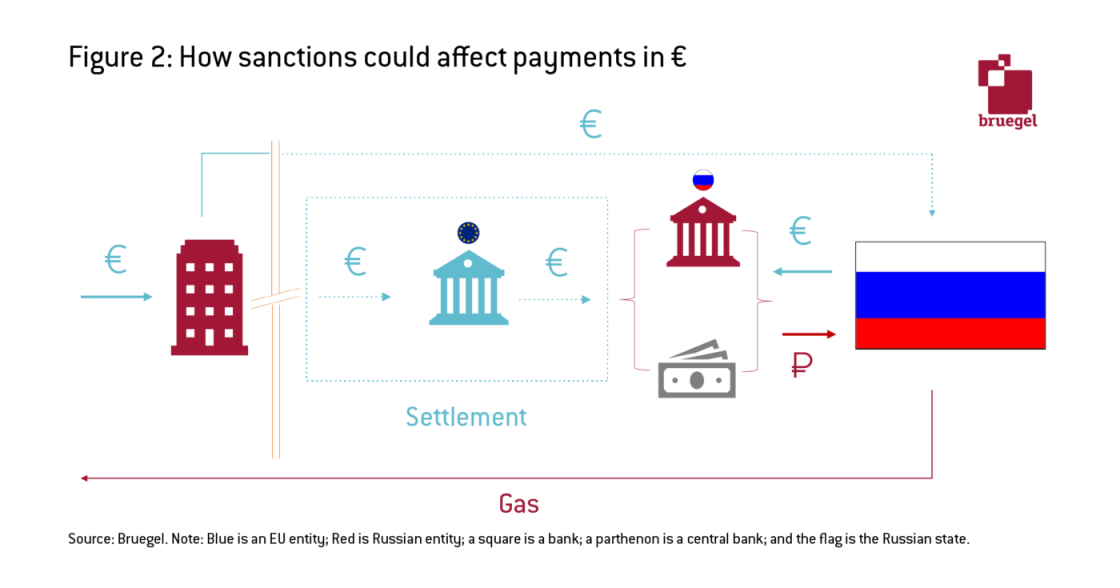

Sanctions are such that while the Russian state has a euro claim on Gazprombank, it cannot use it to, say, buy the rubles it needs domestically. Any euro exchange the Russian state might attempt, either via the markets or the Bank of Russia, would have to be settled with Target 2 – the euro area’s settlement system – and would be captured by sanctions (Figure 2).

Sanctions therefore would mean that the flow of euros that gas importers pay is stuck in Gazprombank, just as Russia’s stock of foreign reserves was frozen at the start of the war in Ukraine. In other words, the Russian state’s legal claim on these new foreign assets is suspended.

Payments in rubles

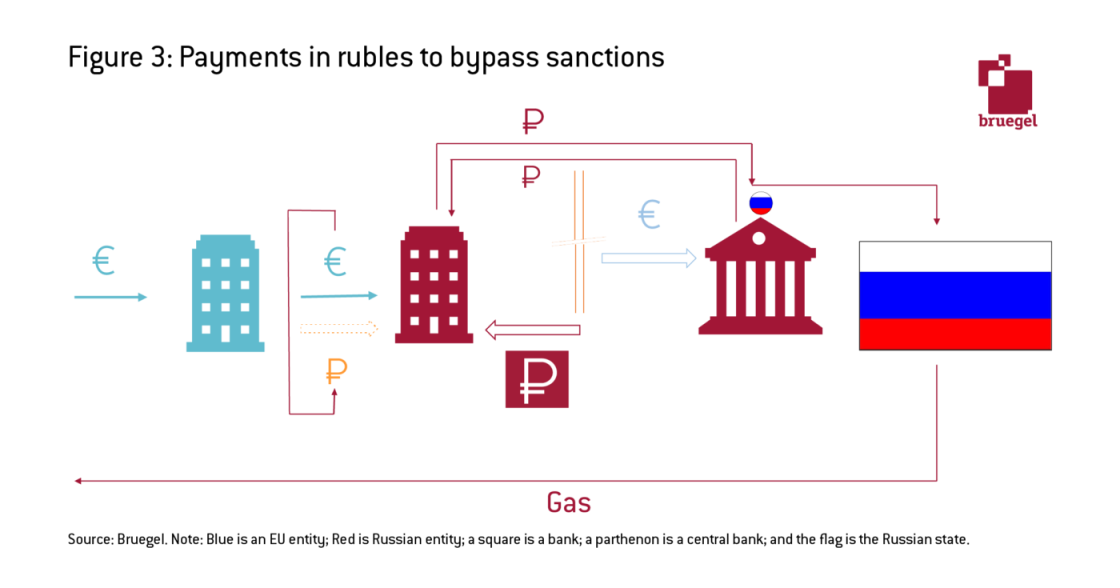

According to the 31 March decree, European gas importers must open both a ruble and a foreign currency account with Gazprombank. Our understanding on how the payment would be done and how this bypasses sanctions altogether is shown in Figure 3. The gas importer’s bank pays euros into the foreign currency account.

The gas importer then asks Gazprombank to exchange the euros into rubles. Gazprombank does this by borrowing rubles from the Bank of Russia, thus increasing its reserves (deposits) at the Bank of Russia. This borrowing can be done against any collateral, including the euros it has received from the gas importer’s bank. Gazprombank then transfers the rubles it has borrowed from Bank of Russia to the gas importer’s ruble account. Gazprombank can then, on behalf of the gas importer, pay out rubles to the Russian state by drawing down on its deposits at the Bank of Russia.

In this way:

- There are no euros involved in transactions with sanctioned entities (Gazprombank borrows from the Bank of Russia in rubles) and therefore no need for any euro settlement at Target 2 involving a sanctioned entity, thereby respecting sanctions.

- The euros paid into Gazprombank remain untouched by sanctioned entities and thus there is no need for any further Target 2 settlement, again respecting sanctions.

- There is an implicit foreign exchange transaction in the exchange of deposits between the Bank of Russia and Gazprombank. As the price of gas is fixed in euros, the exchange rate at which euros are exchanged into rubles should be irrelevant. However, Gazprombank can charge a fee to the gas importer as commission for the foreign exchange operation. Normally foreign exchange commissions are extremely low but, as the market for rubles is probably very illiquid, Gazprombank might ask for a hefty commission, de facto increasing the gas price. This ends up operating as a price instrument in the hands of the Russian state (an indirect indication that this could occur is that the fee applied by Russia’s VTB Bank for ruble/dollar transactions with private customers, which before the war was about 4%, is now three times higher).

- The Central Bank of Russia has a potential euro claim on Gazprombank if this used as collateral for lending to Gazprombank, but this is suspended because of sanctions.

If this approach is followed, at the end of the transaction flow the Russian state has ruble funds with the Bank of Russia that it can access to finance its domestic expenses, without having recourse to monetary financing. However, it cannot access the euros held by Gazprombank as long as sanctions are in place.

An attempt to monetise gas

The value of the ruble and the price of energy correlate such that as the latter increases the currency appreciates. Figure 4 indicates that the opposite happened at the start of the Ukrainian war.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the oil price increased and the ruble devalued, arguably because of the impact of the sanctions. But the ruble has recovered from the initial devaluation. Russia’s stipulation that gas must be paid for in rubles coincided with a significant reinforcement of this development.

Formally, with payments made in rubles via Gazprombank, sanctions are not violated. However, there might be an issue with a breach of contract. As contracts are in euros, as far as the European gas importer is concerned, payments are finalised as soon as the euro transfer is made. However, the decree specifying ruble payments means that, for the Russian exporter, the payment is not finalised until ruble payments are made. While there is no exchange risk as the importer pays euros, during the period between the transfer of euros to Gazprombank and their exchange into rubles, the European importer bears a counterparty risk. In addition, as noted earlier, Gazprombank might charge a fee for the exchange rate transaction, which would be a breach of contract and raise the price of gas by stealth. European countries have raised this concern.

Sanctions are unlikely to be 100% effective. They trigger defensive or counter measures and the final result is uncertain. However, violating sanctions would be costly for Russia: financial entities that might help Russia could ask for hefty compensation, given the risk of being discovered by the European or US authorities. Sidestepping the sanctions altogether by requiring payments in rubles can be advantageous for the Russian authorities.

Recommended citation:

Demertzis, M. and F. Papadia (2022) ‘A sanctions counter measure: gas payments to Russia in rubles’, Bruegel Blog, 19 April

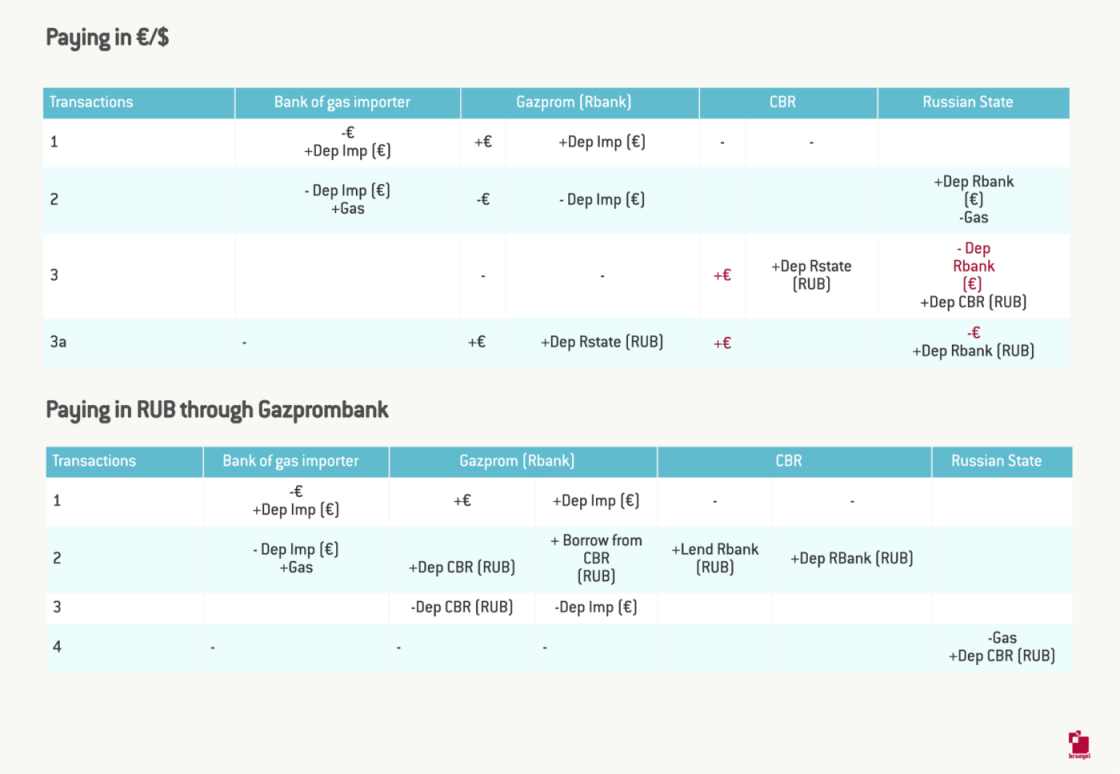

Appendix

We reproduce the flow of transactions with the help of simplified balance sheets. The transactions are not necessarily to be understood as sequential, they rather identify the changes involved in paying for gas in dollars or euros, or in rubles. Transactions potentially affected by sanctions are in red. For simplicity reasons, Gazprom and the Russian State are consolidated into a single entity, under the latter’s name. Analogously, the foreign exchange ruble/€ transaction is, in the second table, implicit in an exchange of deposits between Gazprombank and Bank of Russia, avoiding the introduction of another bank intermediary as the counterpart of Gazprombank in the foreign exchange transaction.