How have sanctions impacted Russia?

In this paper we assess both the immediate economic impact and the likely longer-term impact of sanctions on the Russian economy.

Executive Summary

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered a series of sanctions imposed by the European Union, the United States and others. Sanctions included restrictions on Russia’s financial industry, its central bank and its coal and oil exporters, in addition to general export controls. Meanwhile, foreign companies have withdrawn voluntarily from the Russian market as a result of a ‘self-sanctioning’ trend. We assess the impact these sanctions have had on Russia’s economy in the immediate aftermath of the invasion and more structurally.

- Russian fiscal revenues have not suffered from sanctions sufficiently to reduce the length of this war. Effective management by the Bank of Russia has prevented financial instability and has therefore also protected the real economy. However, this picture of economic containment is coming to an end.

- Russia’s fiscal revenues are now beginning to take a hit; given the breadth of sanctions, the economy will suffer in the medium to long term. The voluntary departure of a large number of western firms, eventual energy decoupling by the EU and Russia’s inability to find equal alternatives will damage the Russian economy severely. As the Russian economy closes in on itself, it will become harder to find reliable data to evaluate the extent of the hit.

- Still greater sanctions coordination across the globe is needed to isolate the Russian economy, limit the flow of income into Russian coffers and therefore help stop the war.

1 Introduction

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a series of sanctions imposed by the European Union, the United States and others1. Sanctions have included restrictions on Russia’s financial industry, its central bank and its coal and oil exports, in addition to general export controls. Meanwhile, foreign companies have withdrawn voluntarily from the Russian market as a result of their own risk calculations and, importantly, because of pressure of public opinion. This ‘self-sanctioning’ is of profound importance for Russia’s economic prospects.

In this paper we assess both the immediate economic impact and the likely longer-term impact of sanctions on the Russian economy. This assessment also help identify what other measures the EU should consider imposing if it wants to help end the war in Ukraine. However, the effects of sanctions remain unclear. The war continues with no obvious end in sight. Sanctions are only now, in late 2022, beginning to have an impact on Russia’s ability to generate revenues. An EU oil embargo will enter into force at the end 2022, and should cause more visible effects on Russia’s balance of payments and fiscal accounts. However, thanks to the ‘Fortress Russia’ strategy and the Bank of Russia’s skillful response, financial-sector sanctions have failed to create a financial crisis in Russia, explaining the smaller-than-anticipated economic contraction2. In addition, many Russian institutions are not yet under full sanctions and continue to benefit from access to international finance.

Nevertheless, there has been an impact on the broader Russian economy. Second and third quarter data shows clearly that some sectors, including car production and aviation, are being hit hard. Russia is highly reliant on global value chains for its investment capacity. Export controls and self-sanctioning by foreign companies will reduce further Russia’s already meager potential growth (Dabrowski and Collin, 2019). Increased brain drain will also reduce the country’s human capital, particularly at the high skill level. Predictions about the impact on the Russian economy this year were originally very pessimistic, but the September 2022 International Monetary Fund estimates were less so, forecasting a contraction of 3.4 percent3.

With the EU decoupling from Russia in all ways, including a permanent energy decoupling, Russia is losing a very important economic partner. While Russia may find ways to mitigate some sanctions-related effects, the overall loss in economic activity will likely be permanent, even before the more medium- and long-term impacts on potential growth kick in.

But the fact that the real economic repercussions will not manifest themselves immediately implies that the Russian economy will not constrain the ability of the Russian leadership to sustain the war in Ukraine. Here, the EU has more to do.

2 Russia’s slowly deteriorating macro-outlook

2.1 Russia still enjoys a large balance-of-payments surplus

There is a perception that sanctions have not been effective in doing economic harm to Russia and therefore have not undermined its capacity to continue the war in Ukraine4. This view is often based on an assessment of Russia’s external accounts. While understandable, the view is grounded in unrealistic expectations as it ignores the fact that an emerging market with a commodity-driven annual current account surplus of more than $120 billion in 2021 prior to sanctions is largely shielded from dramatic external shocks (Hilgenstock and Ribakova, 2020c).

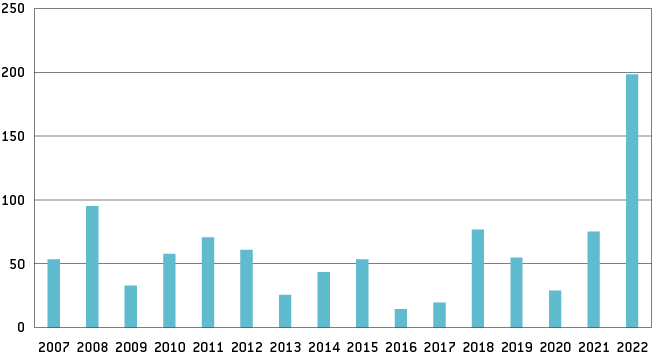

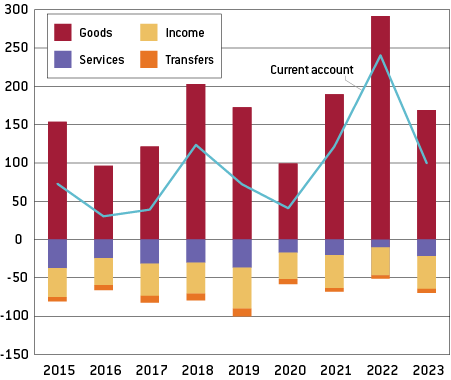

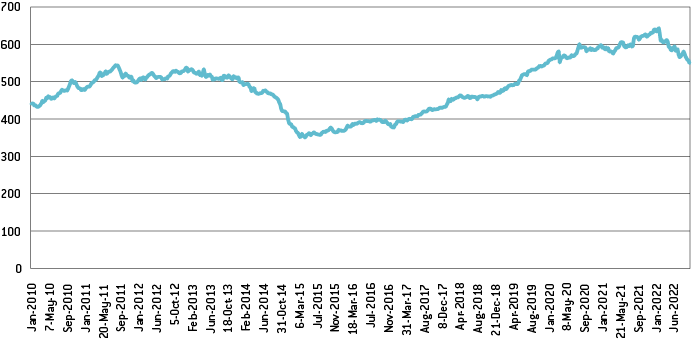

Russia’s current account has indeed improved dramatically in 2022. The surplus for January-September stood at $198.4 billion – roughly $120 billion higher than for the same period in 2021, and more than double the previous record (Figure 1). Two main developments explain this outcome: sky-high prices for major Russian exports and lower imports since the onset of the war5.

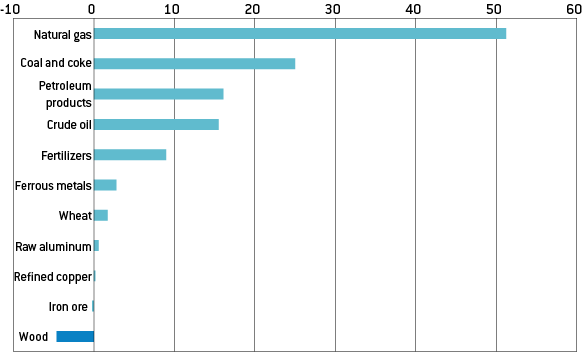

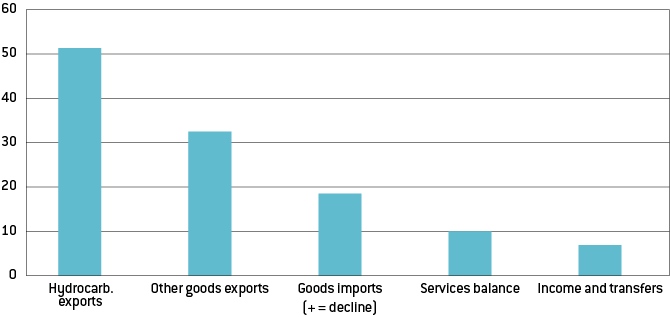

By applying 2022 prices to 2021 export volumes of key goods, we estimate that Russia’s export income has risen by roughly $120 billion year-to-date because of higher prices. The largest contribution to this price effect (above 40 percent) comes, not surprisingly, from natural gas, with coal, petroleum products and crude oil also making significant contributions (Figure 2). Based on commodity price futures, the price rise for all of 2022 should remain around this $120 billion level. Since exports, especially of natural gas, are often governed by long-term contracts, these estimates likely overstate the actual effect. However, they show that elevated commodity prices more than offset reductions in export volumes.

Figure 1: Russia’s current account reached a record high $198 billion during Jan-Sept 2022

Source: Bank of Russia.

Figure 2: High energy prices contributed significantly to the increased value of Russia exports, Jan-Sept 2022

Source: Bruegel based on Bank of Russia, Rosstat. Note: Price effect calculated by holding 2021 volumes constant and applying 2022 spot prices.

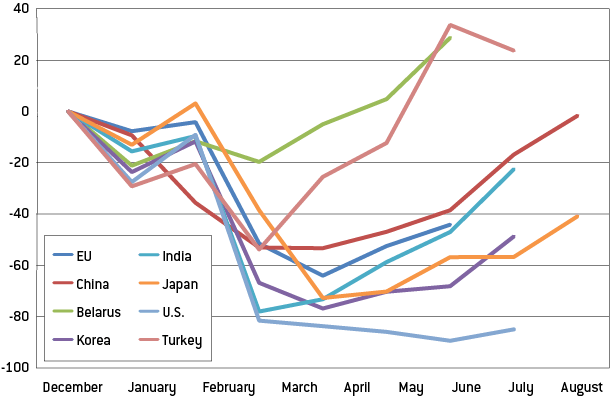

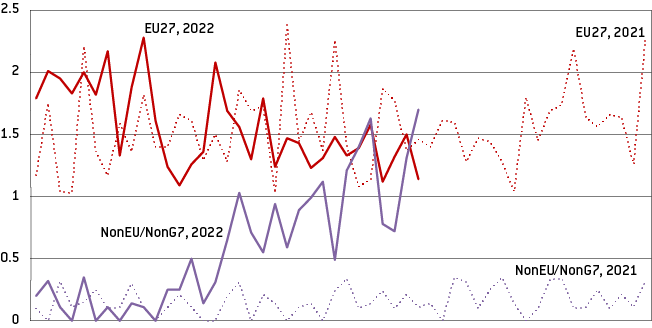

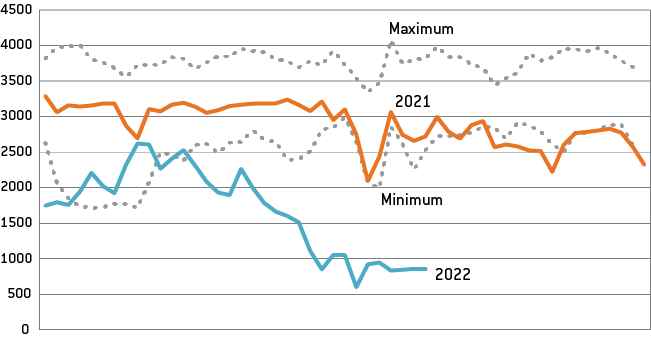

The second factor behind the increase in Russia’s current account balance is the decline in Russian imports. Official trade statistics from the country’s authorities do not extend beyond February 2022, but imports in subsequent months can be estimated by looking at data from Russia’s main trading partners (Figure 3)[6]. By this measure, Russia’s imports fell by roughly $8.5 billion in March 2022 compared to the previous month, and by somewhat more in April, before recovering from May to August (Figure 4). The bounce back has been driven by imports from China, which have returned to pre-war levels, and by soaring imports from Belarus and Turkey. The total for the first half of 2022 will likely be $8 billion to $9 billion lower than in the first half of 2021 (or a 6 percent drop year-on-year). While it is reasonable to assume that Russia’s imports will continue to increase in the coming months, especially as it finds alternative sources for key goods, the 2022 total could be $20 billion lower than 2021. Together with the export price effect, the reduction in imports could therefore mean a roughly $140 billion shift in the trade balance in Russia’s favour – an amount that cannot be cancelled out by sanctions on Russian exports.

Figure 3: Russian imports 2022 by origin

Source: Bruegel based on national authorities.

Figure 4: Recovery in Russian imports

Source: Bruegel based on national authorities.

As commodity prices are likely to remain high for the rest of 2022, a Russian current account surplus of close to $240 billion is expected for the full year (Figures 5 and 6). Relatively high prices will also continue to support the current account in 2023, despite the EU embargo on crude oil and petroleum products and despite Russia’s decision to cut natural gas flows to Europe. We estimate a surplus of around $100 billion in 2023 – a substantial drop compared to 2022, but nevertheless robust current account dynamics.

Such numbers might suggest sanctions are failing to change foreign-exchange dynamics for the time being and may be counterproductive. However, the combination of a large and likely persistent fall in Russian imports, and the permanent decoupling of European economies from Russian energy supplies, will have significant negative consequences for the Russian economy in the medium to long run7. A In addition, more, potentially biting, sanctions could be imposed. Restrictions on oil and gas shipments, for example, would cut off Russia from alternative export destinations and, ultimately, would weigh heavily on production.

Figure 5: Current account surplus to reach $240 billion in 2022

Source: Bruegel.

Figure 6: Higher hydrocarbon exports drive shift in current account

Source: Bruegel.

2.2 Russia’s fiscal balance under pressure

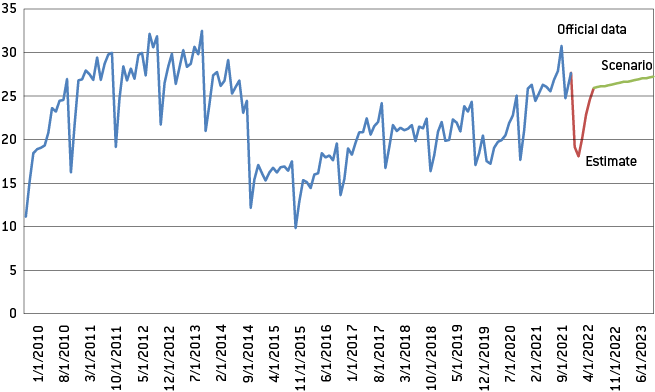

While important for overall macroeconomic vulnerabilities, foreign exchange inflows are less critical than fiscal revenues for Russia’s ability to continue its war against Ukraine. Revenues appeared to hold up during the first months of the war. But a combination of sharply lower oil and gas revenues in local currency terms and elevated expenditure pushed the federal government’s balance into deficit in June, July and August 2022.

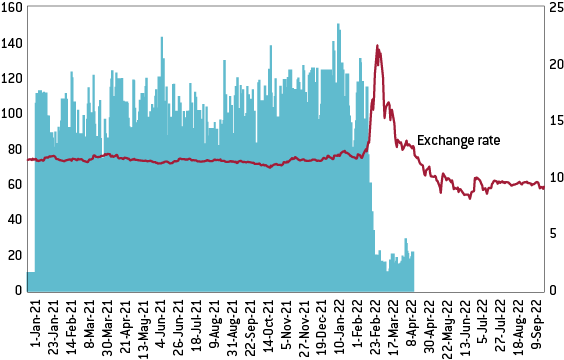

From January to May, federal budget revenues were almost 30 percent higher than in the same period in 2021. This more than made up for higher expenditure and generated the largest January-May surplus on record at 1.6 trillion rubles. However, the situation then changed dramatically as revenues fell (Figure 7), likely because of the strong ruble, which has weighed on the value of hydrocarbon production and exports in local currency terms. We estimate that a 10 ruble shift in the dollar exchange rate triggers a 1.2 percent of GDP change in revenues from crude oil, petroleum products and natural gas through its effect on extraction taxes and export duties (Figure 8). We also find that the effect of a $10 per barrel move in the price of crude oil and petroleum products amounts to roughly 0.8 percent of Russian GDP, and a $10 per megawatt hour of natural gas amounts to about 0.5 percent of GDP.

The 1.45 trillion ruble deficit from June to August wiped out roughly 90 percent of the previously accumulated surplus. Should current fiscal dynamics persist for the remainder of 2022, Russia will likely see a budget deficit of around 2 percent of GDP for the full year.

While pressure on Russia’s fiscal balance has increased, expenditure cuts would likely be possible should revenues continue to fall short. In addition, the finance ministry should, if needed, be able to increase considerably net issuance of domestic debt. Russia’s financial sector is dominated by public banks (accounting for more than two-thirds of total assets) that have room to increase their holdings8. However, expenditure cuts would have significant medium- and long-term consequences for the economy and the welfare of the Russian people. But Russia succeeded in building up fiscal buffers through significant fiscal consolidation after 2014, when sanctions were first imposed following the annexation of Crimea. In this respect, the Fortress Russia strategy is working as intended.

That does not mean that there is no room for further measures to impact Russia’s fiscal accounts. Lower gas exports to Europe, for example, will inevitably mean lower production and, thus, lower revenues. However, the exchange rate functions to some degree as an automatic stabiliser. Lower foreign exchange inflows from trade, all else being equal, weigh on the ruble and thus increase the local-currency value of the remaining exports and increase fiscal revenues.

Figure 7: The federal government balance shifted to a deficit in June-August 2022

Source: Russia Federal Treasury.

Figure 8: Impact of energy prices and the ruble exchange rate on the fiscal balance

Source: Bruegel.

2.3 The Bank of Russia’s response has helped stabilise the financial sector

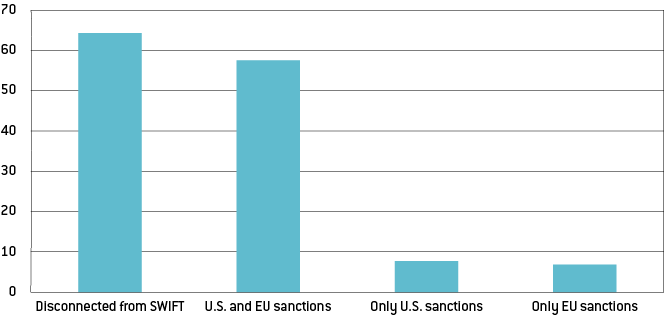

Quite comprehensive sanctions on Russia’s financial sector were expected to have a substantial impact, but appear to have failed to achieve the desired effect. Despite sanctions on most financial institutions, including asset freezes, loss of access to the US dollar and the euro, and disconnection from the SWIFT payment infrastructure, the financial system has stabilised, mainly because of competent management by the Bank of Russia. Sanctions on Russia’s central bank assets were much stronger than expected and have had considerable impact. But the Bank of Russia continues to hold large amounts of foreign currency for potential intervention.

We estimate that close to two-thirds of Russia’s banking system in asset terms has lost access to the US and/or European financial systems and, thus, to the world’s two most important currencies9. Most large banks have been disconnected from SWIFT – a step long considered a ‘nuclear option’ (Figure 9)10. Nevertheless, structural liquidity conditions have returned more or less to pre-sanctions levels, following a short period of stress in March 2022 (Figure 10). In addition, various channels continue to enable Russian banks to interact with the outside world. However, the financial system faces considerable challenges. According to the Bank of Russia, Russian banks lost close to $25 billion in the first half of 2022, largely from foreign currency operations11. It should also be noted that there are significant exemptions to financial-sector sanctions, including for energy-related transactions. These could be removed in the future as European imports of Russian oil and gas continue to decline.

Figure 9: Share of the Russian financial system under sanctions

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission, US Treasury, banki.ru.

Figure 10: The banking system’s structural liquidity surplus has returned to pre-war levels

Source: Bank of Russia.

Despite its Fortress Russia strategy, Russia has not succeeded completely in anticipating western sanctions. Early and drastic measures related to assets held abroad reduced Bank of Russia reserves by 40 percent. As a result, restrictions on foreign-currency access and capital controls have had to be more extensive than anticipated. However, the balance-of-payments dynamics (section 2.1) mean that Russia might be able to rebuild reserves quite quickly, underscoring that to be effective, sanctions must be changed and updated constantly. Since the start of the war, the Bank of Russia has lost around $95 billion in reserves (Figure 11), for reasons other than sanctions, but nevertheless roughly $300 billion remains available for intervention should it be needed.

Figure 11: The Bank of Russia’s reserves declined by close to $100 billion

Source: Bank of Russia.

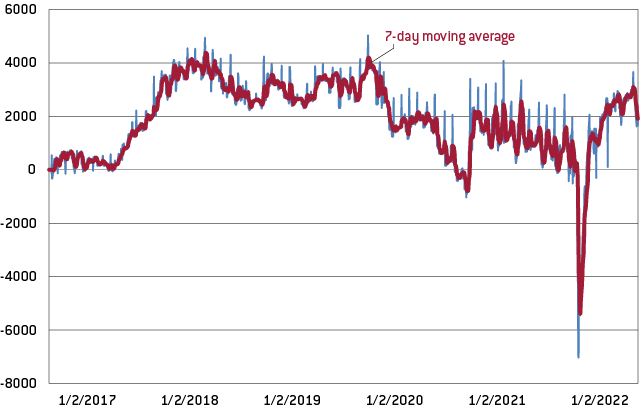

Figure 12: Ruble trading volumes fell sharply after sanctions were imposed

Source: Bruegel based on Bank of Russia, Bloomberg.

2.4 The strong ruble is not a sign of the ineffectiveness of sanctions

The somewhat surprising strength of the Russian currency has led some to conclude that the overall macro situation is strong12, but this is not correct (Guriev, 2022). Volumes transacted have dropped sharply, implying that the sanctions are working as intended.

Immediately following the imposition of sanctions, the ruble dropped from about 70-75 to the dollar to close to 140 to the dollar. This market reaction was very short-lived; by April 2022, the exchange rate returned to below pre-invasion levels13. It is now fluctuating at about 60 rubles to the dollar (Figure 12). Two main factors have influenced this.

First, and crucially, volumes of rubles traded fell to about a third of what they were before the war (Figure 12). A much smaller volume of transactions implies that the price signal is both more volatile and less informative in terms of the underlying fundamentals. The reduction in volumes transacted is the result of sanctions and capital controls that stop non-residents from taking money out of the country. This may only contribute marginally to overall exchange rate dynamics, but has been challenging for investors, especially those holding ruble-denominated government debt (so-called OFZ) and foreign companies withdrawing from the Russian market.

Also, for an extended period, the Bank of Russia imposed strict capital controls, ordering banks not to sell foreign currency to retail clients and introducing a $10,000 cap on cash withdrawals from foreign currency-denominated retail accounts. While the cap has since been largely lifted, and Russian citizens can transfer up to $1 million per month, supplies of foreign currency are extremely limited and withdrawals can take considerable time. In addition, even the smallest transactions are at risk of getting stuck in correspondent bank accounts for weeks if not months, as international banks are wary of facilitating transfers by Russian clients for compliance reasons.

Second, current account dynamics are, as outlined in section 2.2, extremely favorable because of shrinking imports and high prices for the main export goods. In addition, the central bank, starting on 28 February, required exporters to convert 80 percent of their revenues into rubles, before reducing the share to 50 percent in late May as concerns over ruble weakness and foreign exchange liquidity subsided14. Thus, the current exchange rate is not a reflection of the value of the Russian economy’s fundamentals. Rather, it is a testament to the fact that financial sanctions are isolating the ruble internationally.

2.5 Export controls and self-sanctioning contribute to a bleak macro-outlook

While the Russian economy is undoubtedly feeling a hit from sanctions, the immediate effect is much smaller than initially projected (Hilgenstock and Ribakova, 2022a). In the second quarter of 2022, GDP fell by 4 percent year-on-year, and the decline could reach 7 percent in the third quarter according to the Bank of Russia (2022). Publicly, Russia’s government expects a contraction of around 2.9 percent in 2022, while the central bank expects a contraction of 4 percent to 6 percent for the full year15. Internal documents, however, show more pronounced concerns over the economic impact of sanctions16. Importantly, as geopolitical circumstances are unlikely to change in the near term, no strong rebound should be expected in the coming years. Rather, sanctions will have a permanent effect on the economy.

Two main factors are responsible for weakening activity in Russia: export controls imposed by the EU, United States and others, and the withdrawal of foreign companies in response to public pressure.

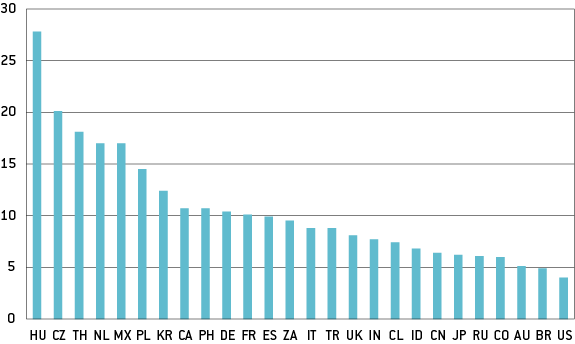

Figure 13: Russia, import content by country

Source: Bruegel based on OECD.

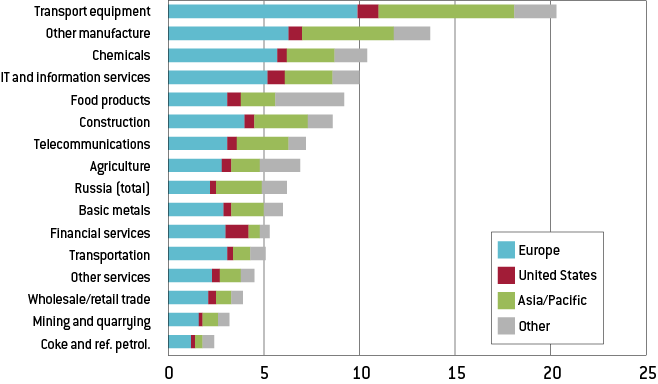

Figure 14: Russia, import content by sector

Source: Bruegel based on OECD.

Export controls have seriously impeded the Russian economy’s ability to acquire components for manufacturing activities. While Russia’s economy is less reliant on imports than most other large, advanced economies and emerging markets, some sectors are highly exposed, especially the manufacturing of transportation equipment, chemicals, food products and IT services (Figures 13 and 14).

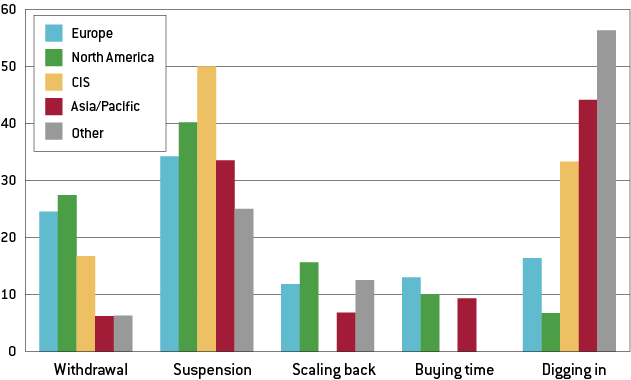

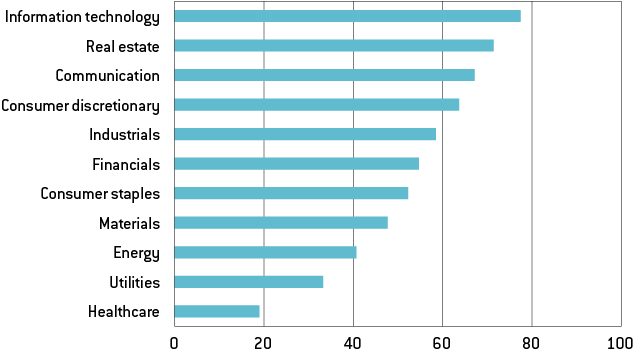

The departure of many foreign companies has done additional damage to sectors in which they played a strong role, including auto production and transportation. Research by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE, 2022) and Yale University (Yale, 2022) has shown that, not surprisingly, companies from Europe and North America have been most decisive in temporarily or permanently halting activities, and higher shares of foreign companies remain in industries such as energy and materials, compared to IT services, real estate and communications (Figures 15 and 16). Only about 40 companies have been able to divest and/or write off their Russian investments. Russian authorities have made it harder for non-residents to exit and take their money abroad, and also plan to not grant permission for banks to sell their holdings while sanctions are imposed on Russian banks abroad17.

Figure 15: Status of foreign companies in Russia by origin

Source: Bruegel based on Yale (2022). Note: withdrawal = totally halting Russian engagements or completely exiting Russia; suspension = temporarily curtailing most or nearly all operations while keeping return options open; scaling back = reducing significant business operations but continuing others; buying time = postponing future planned investment/development/marketing while continuing substantive business; digging in = continuing business-as-usual in Russia.

Figure 16: Extent of foreign companies' departure differs by sector

Source: Bruegel based on Yale (2022).

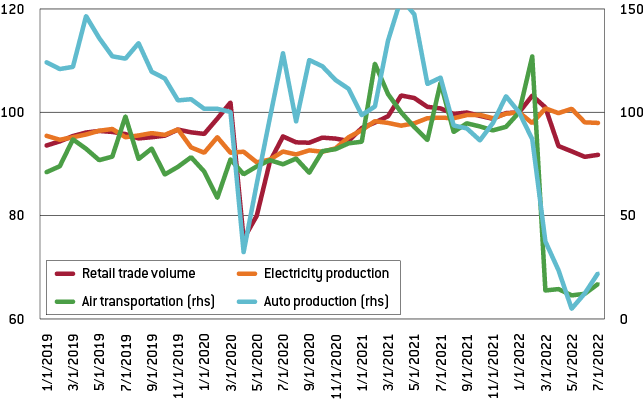

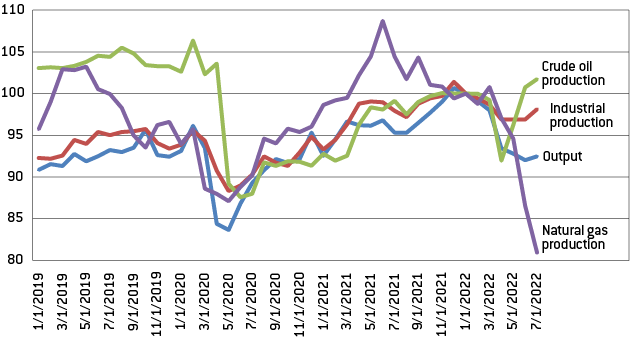

Releases of high-frequency data for the second and third quarter 2022 allow an initial assessment of the impact of sanctions to be made, and to distinguish the impacts on different sectors (Figures 17 and 18). The withdrawal of foreign car manufacturers and the shortage of inputs has hit passenger car production extremely hard, with a 95 percent decline in May 2022 compared to May 2021. Air transportation has also collapsed following the cancellation of aircraft leases and maintenance contracts, and the closure of several countries’ airspaces to Russian planes. Crude oil production has rebounded after a drop in April, and overall industrial production appears relatively strong, but natural gas production has fallen sharply, especially in July (at -19 percent relative to January 2022). Altogether, Rosstat’s monthly output tracking shows six consecutive months of decline since January, totaling 8.1 percent, with April most negative at -4.6 percent18. Should output remain at the current level for the rest of 2022, the full-year decline would amount to only 2.3 percent. However, this indicator does not include all economic activity as it misses, most importantly, parts of the services sector, and may understate the depth of the recession.

We estimate the likely overall GDP contraction at about 5 percent to 6 percent. This is a considerable revision from March-April 2022 forecasts, which put the output decline at 12 percent to 15 percent (Hilgenstock and Ribakova, 2022a). The most important factor explaining the difference is that sanctions failed to trigger a crisis in Russia’s financial system, which would have weighed heavily on the economy. There is still substantial uncertainty around the forecast because of data issues and because of Russia’s partial mobilisation in September of close to 300,000 men, which has led many to flee the country19.

Figure 17: Export controls have had a big impact on activity

Source: Rosstat.

Figure 18: Natural gas production is down sharply

Source: Rosstat.

3 The importance of energy sanctions

Canada, the United States and Australia have banned all imports of Russian oil, while the United Kingdom has announced a phase-down to zero at the end of 2022. Given the limited dependence of these countries on Russia (between 1 percent and 5 percent of demand), these announcements have no significant impact. The European Union, which has traditionally been much more dependent on Russian oil imports (25 percent of demand), agreed only at the end of May 2022 to stop seaborne imports of Russian oil at the end of the year (McWilliams et al, 2022a). Only at the start of 2023 will more than 90 percent of Russia’s previous oil exports to the EU be banned.

Figure 19: Russian crude oil and oil product exports (2021, million tonnes)

Source: Bruegel based on BP and Eurostat.

Nevetheless, the EU’s decision is very significant and will have major repercussions for Russia’s role as a main oil exporter in the medium and longer term.

In the meantime, however, Russia has continued to earn substantial oil revenues. Crude oil exports from Russia’s western and Arctic ports have remained strong. These ports historically served European consumers, and whether flows can be re-directed to non-EU countries will be pivotal in determining the ultimate impact of sanctions. Though there has been a small reduction in Russian exports to the EU, other countries including India and China have increased Russian oil purchases, more than compensating for the loss of the EU market (Figure 20). However, these countries currently buy Russian oil at a significant discount to global prices20. As European demand disappears third countries will find it easier to negotiate discounts.

Russia also exports oil via pipeline to Europe and China, and via eastern ports. These flows are still not subject to any planned sanctions.

Figure 20: Weekly Russian crude oil exports from western ports

Source: Bruegel Russian crude oil tracker, https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/russian-crude-oil-tracker.

There is one way to significantly undermine Russian oil exports. Over 90 percent of the world’s oil tankers are insured via the International Group of P&I Clubs, a London-based association of insurers (S&P Global, 2022). In agreement with the UK, the EU also introduced in its sixth package of sanctions against Russia, a ban on insurance for ships carrying Russian oil from the start of 202321. EU operators will be prohibited from insuring and financing the transport, in particular through maritime routes, of Russian oil to third countries. As finding new sources of insurance is difficult and costly, this measure would have a meaningful impact on Russian exports to non-EU countries. Fearful of the potential repercussions of this measure on global oil market, the United States pushed – most notably at the G7 level – to replace the EU’s blanket insurance ban with a mechanism linked to an oil price cap22, under which insurance would be offered to ships transporting Russian oil only when the price cap is respected. The G7 agreed this price cap in September23. Since then, the EU has modified its previous oil sanction scheme and introduced – with its eighth sanctions package24 – the option for EU operators to insure oil tankers transporting to third countries Russian oil traded below the agreed price cap. The aim of this move, representing a watering-down of the EU previous oil sanction scheme, is thus that Russian oil will continue flowing at lower prices, removing windfall profits, but avoiding the worst global economic consequences.

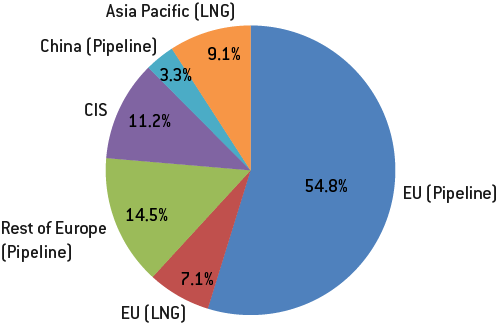

When it comes to natural gas, no sanctions have been introduced. Instead, Russia has sanctioned its own gas supply, blackmailing European countries by progressively cutting its gas exports to Europe – now down to around 20 percent of their 2021 levels (McWilliams et al, 2021).

Figure 21: EU and UK natural gas imports from Russia

Source: Bruegel; see https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-natural-gas-imports.

The consequences of this are that EU energy policy will now have to be independent of Russian imports (Poitiers et al, 2022). While this has caused political tension and will have economic effects in Europe during winters 2022/2023 and 2023/2024, in the medium run, the consequences will be substantial for Russia’s gas-export business. Russia will need to close a sizeable portion of its gas-export infrastructure as around 60 percent of its gas exports go west to the EU and UK. These cannot easily be redirected. Like sea-borne oil, Russia has some ability to redirect LNG exports away from the EU. Unlike oil, the overwhelming majority of the EU’s imports are via pipeline and Russia will not be able to redirect these flows, which accounted for 55 percent of exports in 2021 (Figure 22). In the future, it is possible that the EU will again import gas from Russia. If so, these flows should be subject to explicit price and volume restrictions agreed at EU level (Ockenfells et al, 2022; Hausman et al, 2022).

Figure 22: Russia natual gas exports (2021)

Source: BP.

Russia currently exports natural gas from eastern fields to China through the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline. Western fields, which serve European markets, are not connected to this export route and cannot be redirected to China. The Power of Siberia 2 pipeline will connect the two fields and eventually enable Russia to redirect flows eastwards. However, the project will take many years, with an estimated realisation date of 2030 (Oxford Economics, 2022). Meanwhile, without European customers, Russia will be forced to close production sites at significant long-term capital cost. Export revenues from gas will dry up. Attempts to diversify export routes by building new liquified natural gas export capacity are hindered by lack of access western technology, and in any case will take years. Furthermore, commercial conditions in the Chinese market are much worse for Russia than those in the European market. Before the Ukraine war, Russia was estimated to charge $3 per million British thermal unit (MMBtu) for deliveries to China via the Power of Siberia pipeline, while the estimated charge for deliveries to Europe was $10-$25/MMBtu. The best long-term case for Russia’s gas business is to serve China as the dominant buyer. In the short-run, the situation is much more dire.

It should also be noted that Europe – notably thanks to increased liquified natural gas imports – has so far managed to replace significant volumes of gas supplies that previously came from Russia (McWilliams et al, 2021). EU countries have also agreed to reduce their gas consumption by 15 percent between 1 August 2022 and 31 March 202325. An average reduction of 15 percent in gas demand across the EU should be sufficient to compensate for a complete stop to Russian gas imports in winter 2022/2023 (McWilliams and Zachmann, 2022). The best solutions for prosperity without Russian gas will involve deeper cooperation between EU countries, and this must be the primary response to Russia’s gas cuts (McWilliams et al, 2022b, 2022c).

4 Conclusions

By late 2022, Russian revenues had not suffered as much as intended by western sanctions regimes. Consequently, Russia has been able to continue to finance its war in Ukraine. This may soon start to change.

The effects of sanctions on the Russian economy have been slow to manifest. Financial stability has been maintained by decisive policy measures taken by the Bank of Russia, which have prevented knock-on effects on the real economy. The EU’s energy strategy of sequencing – first meeting its own energy needs and only then sanctioning – has meant continued revenue streams into Russia.

This does not mean however, that the Russian economy will not suffer in the medium to long-turn. The voluntary departure of a large number of western firms, the EU’s eventual energy decoupling and Russia’s inability to find equally good customers elsewhere will cause severe damage to the Russian economy. It may however become progressively more difficult to evaluate the impact of sanctions on the Russian economy, because the Kremlin is blocking public access to economic statistics (Starostina, 2022).

The main takeaway is that greater coordination of sanctions across the world is needed to isolate the Russian economy. Bringing forward the end-2022 EU embargo on Russian oil would also help limit the flow of income into Russian coffers, and would therefore also help bring an end to the war.

References

Bank of Russia (2022) Monetary Policy Report No. 3, 1 August, available at https://www.cbr.ru/Collection/Collection/File/42215/2022_03_ddcp_e.pdf

Dabrowski, M. and A. Mathieu Collin (2019) ‘Russia’s growth problem’, Policy Contribution 2019/04, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp_attachments/PC-04_2019.pdf

Darvas, Z. and C. Martins (2022) ‘Russia’s huge trade surplus is not a sign of economic strength’, Bruegel Blog, 8 September, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/russias-huge-trade-surplus-not-sign-economic-strength

Guriev, S. (2022) ‘The Incredible Bouncing Ruble’, Project Syndicate, 12 April, available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/russia-ruble-reasons-for-appreciation-are-bad-for-economy-by-sergei-guriev-2022-04

Hausmann, R., A. Łoskot-Strachota, A. Ockenfels, U. Schetter, S. Tagliapietra, G. Wolff and G. Zachmann (2022) ‘How to weaken Russian oil and gas strength’, Science 376, p. 469, available at https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abq4436

Hilgenstock, B., G. Meisels and E. Ribakova (2020a) Market Interventions: U.S. Sanctions on Russia, Institute of International Finance, 19 February

Hilgenstock, B., G. Meisels and E. Ribakova (2020b) Russia – Safe Haven Among EM, Institute of International Finance, 20 May

Hilgenstock, B., G. Meisels and E. Ribakova (2020c) Russia – Low Sensitivity to External Shocks, Institute of International Finance, 18 March

Hilgenstock, B., C. Lowery, G. Meisels, J. Renier and E. Ribakova (2022a) Russia Sanctions: Climbing the Escalation Ladder, Institute of International Finance, 28 February

Hilgenstock, B., C. Lowery, G. Meisels and E. Ribakova (2022b) Russia Sanctions: Adapting to a Moving Target, Institute of International Finance, 8 June

Hilgenstock, B. and E. Ribakova (2022a) Russia – Economy to Contract Sharply in 2022, Institute of International Finance, 23 March

Hilgenstock, B. and E. Ribakova (2022b) Russia – Payments Systems and Digital Ruble, Institute of International Finance, 2 February

Hilgenstock, B. and E. Ribakova (2022c) ‘Countering economic coercion: How can the European Union succeed?’ Policy Brief, Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), June, available https://feps-europe.eu/publication/countering-economic-coercion-how-can-the-european-union-succeed/

KSE (2022) SelfSanctions / LeaveRussia, Kyiv School of Economics, available at https://kse.ua/selfsanctions-kse-institute/

Lenaerts, K., S. Tagliapietra and G. Zachmann (2022) ‘A possible G7 price cap on Russian oil: issues at stake’, Bruegel Blog, 13 July, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/possible-g7-price-cap-russian-oil-issues-stake

McWilliams, B., G. Sgaravatti and G. Zachmann (2021) ‘European natural gas imports’, Bruegel Dataset, available at https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/european-natural-gas-imports/

McWilliams, B., S. Tagliapietra and G. Zachmann (2022a) ‘Europe’s Russian oil embargo: significant but not yet’, Bruegel Blog, 1 June, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/europes-russian-oil-embargo-significant-not-yet

McWilliams, B. and G. Zachmann (2022) ‘European Union demand reduction needs to cope with Russian gas cuts’, Bruegel Blog, 7 July, available at https://www.bruegel.org/2022/07/european-union-demand-reduction-needs-to-cope-with-russian-gas-cuts

McWilliams, B., G. Sgaravatti, S. Tagliapietra and G. Zachmann (2022b) ‘A grand bargain to steer through the European Union’s energy crisis’, Policy Contribution 14/2022, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/grand-bargain-steer-through-european-unions-energy-crisis

McWilliams, B., S. Tagliapietra and G. Zachmann (2022c) ‘Europe Needs a Grand Bargain on Energy’, Foreign Affairs, 8 August, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/europe/europe-needs-grand-bargain-energy

Ockenfels, A., S, Tagliapietra and G. Wolff (2022) ‘Three ways Europe could limit Russian oil and gas revenues’, Nature 604, p. 246, available at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01008-3

Oxford Economics (2022) ‘Power of Siberia 2 is no replacement for pipelines to Europe’, Research Briefing, 18 August, available at: https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/power-of-siberia-2-is-no-replacement-for-pipelines-to-europe/

Poitiers, N., S. Tagliapietra, G. Wolff and G. Zachmann (2022) ‘The Kremlin’s Gas Wars’, Foreign Affairs, 27 February, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/slovenia/2022-02-27/kremlins-gas-wars

Starostina, Y. (2022) ‘Secret Economy: What hiding the Stats does for Russia’, Carnegie Politika, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1 July, available at https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/87432

Yale (2022) ‘Over 1,000 Companies Have Curtailed Operations in Russia—But Some Remain’, Chief Executive Leadership Institute, Yale School of Management, available at https://som.yale.edu/story/0/over-000-companies-have-curtailed-operations-russia-some-remain

Footnotes

[1] For a summary of sanctions imposed since February 2022, see Hilgenstock et al (2022a, 2022b). An analysis of pre-2022 measures can be found in Hilgenstock et al (2020a).

[2] The Fortress Russia strategy describes efforts by Russian authorities since sanctions were first imposed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 to insulate the country’s economy from potential additional measures. See, for example, Hilgenstock and Rivakova (2020b).

[4] Natasha Bertrand and Katie Bo Lillis, ‘Russian sanctions slow to bite as US officials admit frustrations over pace of pain in Moscow’, CNN, 16 September 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/09/16/politics/russia-sanctions-ukraine-slow-economic-pain/index.html.

[5] Darvas and Martins (2022) looked at the import decline in detail.

[6] For a similar approach see Darvas and Martins (2022). Trade statistics, together with many other indicators, have been discontinued because of the war and sanctions.

[7] For an analysis of the European perspective on strategic dependencies, see Hilgenstock and Ribakova (2022c).

[8] Based on February 2022 bank asset data; see https://www.banki.ru/banks/ratings/?LANG=en.

[9] Based on February 2022 bank asset data; see https://www.banki.ru/banks/ratings/?LANG=en.

[10] For a pre-war assessment of SWIFT-related measures see Hilgenstock and Ribakova (2022b).

[11] Reuters, ‘Russian banks lost around $25 billion from Ukraine conflict, central bank official says’, 23 September 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/russian-banks-lost-around-25-billion-ukraine-conflict-central-bank-official-2022-09-23/.

[12] Charles Lichfield, ‘Don’t ignore the exchange rate: How a strong ruble can shield Russia’, New Atlanticist, 26 May 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/dont-ignore-the-exchange-rate-how-a-strong-ruble-can-shield-russia/.

[13] Elina Ribakova, ‘The Ruble Rally Is Real, Sanctions Are a Moving Target’, Barrons, 12 April 2022, https://www.barrons.com/articles/the-ruble-rally-is-real-sanctions-are-a-moving-target-51649708830.

[14] Reuters, ‘Russia hikes rates, introduces capital controls as sanctions bite’, 28 February 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/russian-central-bank-scrambles-contain-fallout-sanctions-2022-02-28/, and Reuters, ‘Russia cuts mandatory FX conversion level for exporters to 50%’, 23 May 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/russia-cuts-mandatory-fx-conversion-level-exporters-50-2022-05-23/.

[15] See Bank of Russia (2022), and Jake Cordell, ‘Russia ups economic forecast, says growth to return sooner than expected – economic minister’, Euronews, 6 September 2022, https://www.euronews.com/next/2022/09/06/ukraine-crisis-russia-economy.

[16] Bloomberg, ‘Russia Privately Warns of Deep and Prolonged Economic Damage’, 5 September 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-05/russia-risks-bigger-longer-sanctions-hit-internal-report-warns.

[17] Vedomosti, ‘Foreign banks will not be able to sell their assets in Russia’, 15 July 2022, https://www.vedomosti.ru/finance/news/2022/07/15/931610-inostrannie-banki-ne-smogut-prodat-svoi-aktivi-v-rossii (in Russian).

[18] The indicator includes five main components: agriculture, industrial production, transportation, trade, communication.

[19] See Reuters, ‘Russia calls up 300,000 reservists, says 6,000 soldiers killed in Ukraine, 21 September 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-partial-mobilisation-will-see-300000-drafted-defence-minister-2022-09-21/, and Thomas Harding, ‘Ukraine war: 250,000 Russian men flee Putin mobilization’, The National, 28 September 2022, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/europe/2022/09/28/ukraine-war-250000-russian-men-flee-putin-mobilisation/.

[20] Stephanie Kelly, ‘Russian oil selling below benchmark amid price cap discussions -U.S. official’, Reuters, 12 October 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/russia-negotiating-with-countries-seeking-oil-below-brent-price-us-official-2022-10-12/.

[22] See comments by EU Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentilloni: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_2802. Lenaerts et al (2022) discussed issues at stake in relation to an oil price cap.

[25] Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1369 of 5 August 2022 on coordinated demand-reduction measures for gas, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022R1369.