Which platforms will be caught by the Digital Markets Act? The ‘gatekeeper’ dilemma

The scope of the Digital Markets Act has emerged as one of the most contentious issues in the regulatory discussion. Here, we assess which companies c

The European Union Digital Markets Act (DMA), proposed by the European Commission in December 2020 to regulate the ‘gatekeepers’ of the digital world, is making progress towards finalisation. The law, in the form of an EU regulation, could take effect in 2022. At the risk of oversimplifying, the DMA can be analysed by two main criteria: (a) its scope, ie which companies will be considered ‘gatekeepers’; and (b) the obligations and restrictions gatekeepers will have to abide by (for a backgrounder, see here).

To be clear, the scope and obligations are interrelated: obligations are tailored to address competitive concerns that arise only if a company is big enough to hold a high degree of market power. But the DMA’s scope has emerged as one of the most contentious issues in the regulatory discussion. We thus focus on the definition of a ‘gatekeeper’, while taking the set of DMA rules as proposed by the European Commission as given.

The DMA definition of ‘gatekeeper’

A gatekeeper is a de-facto digital market bottleneck: EU businesses and consumers find it hard to avoid gatekeepers. According to the Commission’s DMA proposal, a gatekeeper must operate a ‘core platform service’ (CPS). The CPS list includes:

- online intermediation services,

- online search engines,

- online social networking services,

- video-sharing platform services,

- number-independent interpersonal communication services,

- operating systems,

- cloud computing services,

- advertising services provided by a provider of any of the services listed before.

A CPS provider may qualify as a gatekeeper if it meets three qualitative criteria. A gatekeeper:

- “(…) has a significant impact on the internal market;

- it operates a core platform service which serves as an important gateway for business users to reach end users; and

- it enjoys an entrenched and durable position in its operations or it is foreseeable that it will enjoy such a position in the near future.”

The DMA further defines quantitative criteria for gatekeepers:

- “the undertaking to which it belongs achieves an annual EEA turnover equal to or above EUR 6.5 billion in the last three financial years, or where the average market capitalisation or the equivalent fair market value of the undertaking to which it belongs amounted to at least EUR 65 billion in the last financial year, and it provides a core platform service in at least three Member States;

- it provides a core platform service that has more than 45 million monthly active end users established or located in the Union and more than 10 000 yearly active business users established in the Union in the last financial year;

- the thresholds in point (b) were met in each of the last three financial years.”

The Commission has not disclosed the thinking behind these thresholds. However, a reading of the Digital Markets Act Impact Assessment support study annex, which reported an analysis of various quantitative indicators[1] for 19 digital firms[2], shows three things: (1) the exercise carried out by the European Commission was subjective. There is no magic economic formula that would suggest that these are the optimal quantitative thresholds that maximise the efficacy of the restrictions and obligations imposed by the DMA. (2) The approach applied by the European Commission was most likely based on a backward induction process: the Commission had a rough idea of the companies that the DMA should capture, it then crafted the thresholds accordingly, to be sure the bigger players would be included. (3) Finally, the Commission had to make a clear trade-off: too-high thresholds would limit the impact of the DMA because companies with strong market leverage and capable of limiting competition in digital markets could fall out of scope; too-low thresholds would, however, entail high costs, for example burdening companies with compliance duties when they do not restrict competition in the digital market, or increasing pressure on resource-constrained public enforcers.

Experts weigh in

The Commission attempted to reconcile points (1) to (3) by including a review clause in the proposed DMA. According to the proposed DMA Art. 4 and Art. 15, the Commission may revise the list of gatekeepers and conduct market investigations. Essentially, the Commission can establish that a company not meeting the quantitative criteria (a) to (c) may still be considered a gatekeeper if it meets the qualitative criteria (A) to (C).

Various suggestions have been made about how to refine the gatekeeper identification process. Table 1 summarises the most significant (we report whether the contribution was backed by a specific market player or, where relevant, the author’s affiliation). Economists and lawyers would tend to agree with the qualitative criteria. That is no surprise: the qualitative criteria are deliberately general and vague. Criticism from the competition policy community has mainly focused on the proper quantitative criteria to use, to ensure that the qualitative thresholds are met.

One of the most common criticisms of the Commission’s proposal is that it does not take the user or business’s ability to use multiple platforms for the same purpose into account. Take for example, hotel reservations: the user can look for prices and book a room on various available platforms, or directly on the hotel’s website; and the hotel can offer its rooms via the same channels. The extent to which this so-called multi-homing happens and the costs of doing so are measures widely considered in the platform economics literature to assess the entrenchment of market power. If customers can multi-home, they are more likely to escape conditions imposed by one platform by increasing the use of a competing platform. The ability to multi-home has been proposed as a gatekeeper criterion, using quantitative metrics such as the degree of dependence on referral traffic from major search engines, social media and advertising, and the extent of multi-homing by users on each side of the market. For instance, the low switching costs for users of e-commerce or ride-sharing platforms allow for a greater degree of multi-homing than possible for mobile operating systems, which implies purchasing a new device.

Another critique relates to the inherent differences in business models. There cannot be a universal definition of gatekeeper and a general set of rules they should follow: the identification of gatekeepers and respective obligations that derive should take into account companies’ business models (for more information, see here, here and here). Christina Caffarra and Fiona Scott Morton (January 2021) identified roughly three groups of platforms with significantly differing business models: ad-funded digital platforms (including Google, Facebook and Twitter), transaction/matchmaking platforms (including Uber, Airbnb and Amazon), and operating system ecosystem platforms (including operating systems and app stores). The inherent differences between these groups mean that they deploy different strategies to defend their market positions against new competitors.

Michael Jacobides (2021) went beyond the concept of business model and focused on the definition of platform power, which he claimed should be the starting point of any regulatory action. He said it was essential to, first and foremost, “identify some simple, collectively agreed upon principles for establishing platform power and then consider what are the anti-competitive conducts and outcomes that require recourse”. Jacobides proposed a simple framework primarily based on a set of key questions in order to assess platform power[3]. In a 2020 paper, Tiago Prado, who also focused on the topic of market power assessment, used an economic model and concluded that the significant market power (SMP) regulatory framework, used in the telecommunications industry, would still be helpful to assess the digital platform market, subject to some finetuning and adaptation.

Heike Schweitzer (2021) argued that the quantitative thresholds used to designate gatekeepers do not offer any indication of the relevant threshold of bottleneck power. Even though useful to provide clear and immediately applicable guidelines, the absolute values and metrics chosen do not seem to accurately capture the (A)-(C) qualitative conditions. Schweitzer pointed out that the turnover thresholds are met as long as the CPS provider is part of a large parent firm, regardless of its market power. Moreover, the number of users may not exactly reflect the absence of competition if users can multi-home, as explained above. The criteria seem overly focused on size rather than on actual gatekeeping power.

Teresa Ballell (2021) warned that the DMA does not clarify if the thresholds should be calculated for, and the designation applied to, each CPS – service-based approach – or if the focus should be on the provider of the CPS overall – provider-based approach. She argued that a service-based approach would be preferable, since it could prevent unintended consequences hindering the entry of new competitors, which could already be large but not previously operating in the platform industry, and hence not acting as gatekeepers in that market. However, a paper by the Tobin Center for Economic Policy at Yale warned about the downsides of targeting specific platforms when sometimes big players provide a large ecosystem of services from which gatekeeping power is hard to disentangle, and perhaps unfairly attributed to only a few of these platforms. Additionally, large firms could have an incentive to break down their platforms into smaller, more specific services, which alone would not meet the quantitative criteria for designation.

Some authors discuss the definition of core platform services (CPS) as this indirectly affects the definition of gatekeepers and the DMA’s scope. Schweitzer and the Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE) both claimed that the inclusion of some services, such as messaging and cloud computing, is unjustified, given their one-sided nature. For instance, in a case in which a user contracts a cloud service to store information, there is user-platform interaction (single-sidedness) but not subsequent business-end user interaction via the platform (double-sidedness). The Tobin Center paper interpreted this issue of one-sidedness as potentially worrying if it leads to the non-designation of certain platforms. This is because the second quantitative criterion establishing the thresholds for the number of users refers to both end-users and business users.

Oliver Budzinski and Juliane Mendelsohn looked at the CPS list from another perspective and claimed that there is an under-inclusion of services. They pointed out that the DMA treats differently competing services that differ solely on their business models (advertising-financed vs subscription-based). An example could be the inclusion of YouTube (ad-financed) and not Netflix (subscription-based) as video-sharing platform services when there is empirical evidence that these services compete. This could lead to discriminatory treatment, not because of alleged market power, but based on the choice of the business model. The Tobin Center recommended the inclusion of more services in the CPS list, namely web browsers and virtual assistants.

Ballell argued that the selected list of services might become outdated very quickly. Given the dynamic nature of the platform market, which is constantly transforming, a regulation defining a specific list of services “might lack future-proof adaptability”. Hence, while acknowledging that this could, to some extent, compromise the clarity and certainty of the scope of the DMA, the author saw higher benefits in, and recommended the implementation of, a functional definition of CPS, rather than simply a list-based definition. This functional definition could replace the entire list or be added as a general clause. In addition to being more future-proof, this functional definition could provide further clarity on the scope of the DMA in the overall framework of EU regulation on digital services, and prevent inconsistencies or misinterpretations. Likewise, the Tobin Center paper took the view that the DMA could consider a definition of CPS focusing on core functions rather than the form – ie type of platform – in which they are provided.

Finally, various authors flagged the risk that the DMA as proposed by the European Commission is over-inclusive (according to paragraph 148 of the Commission’s summary impact assessment, between 10 and 15 core platform service providers would be captured). The studies pointed out the advantages of focusing efforts and resources on the most noticeable and urgent contestability issues, especially given the novelty and complexity of this new regulation. The gatekeeper designation could then be broadened. An alternative scenario considered by EU legislators, which would require the gatekeeper to provide a minimum of two CPS, would reduce the number of gatekeepers designated by the DMA to five to seven (we discuss this scenario below). In fact, requiring a gatekeeper to provide at least two CPS would go in line with the recommendation of the Centre on Regulation in Europe, from November 2020, to add an additional fourth criterion to the definition of gatekeeper: the ability to orchestrate an ecosystem. According to this recommendation paper, “only the gatekeepers who are active in several connected markets and orchestrate an ecosystem could be subject to the prohibitions and the obligations of the DMA.”

The EU legislative process and the different proposals

The European Parliament will vote to adopt a position on the DMA on 15 December. In June 2021, MEP Andreas Schwab (the Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) parliament committee’s rapporteur on the DMA), proposed higher quantitative thresholds than those proposed by European Commission. Schwab would have raised the quantitative thresholds on EEA turnover and average market capitalisation of the undertaking from €6.5 billion to €10 billion and from €65 billion to €100 billion, respectively. It also suggested that at least two CPS by the same company had to meet the quantitative thresholds for the company to be identified as a gatekeeper.

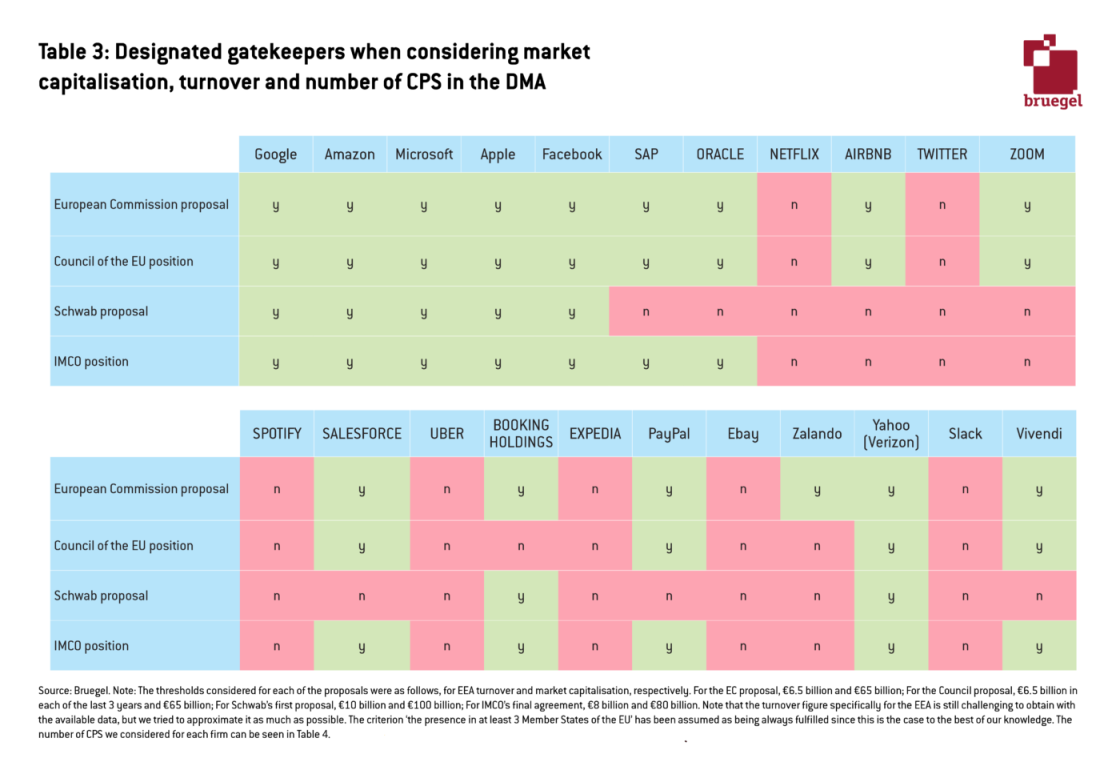

Schwab’s proposal triggered concern in the United States: it was seen as having been engineered so that the DMA’s obligations would apply only to non-EU companies. This proposal was ultimately superseded during the European Parliament process (see below), but we consider it a relevant benchmark: it shows the impact that altering the scope of the DMA could have (Table 3).

The final agreement within the IMCO committee converged on quantitative thresholds of €8 billion turnover and €80 billion market capitalisation (subject to a plenary vote on 15 December 2021).

IMCO has also endorsed the Commission’s proposal to identify gatekeepers on the basis of the existence of one single CPS provided by the company. However, the IMCO position envisages the concept of ‘active user’ to be replaced by users, with the calculation being done for the European Economic Area instead of for the European Union. These adjustments make criterion (b) potential broader and more easily achievable since, even though three more countries would be added, it is enough to provide only one CPS to be potentially considered a gatekeeper and the calculation of the number of users is looser. The IMCO position would also introduce an additional change in the third quantitative criteria. According to the Commission proposal, the thresholds for the number of users should be met over the last three years to reflect an entrenched and durable gatekeeper position. The IMCO position would reduce the fulfilment of the criteria on the number of users to two years.

The position adopted by the Council of the EU also suggests a few changes to the DMA proposal, but is generally more similar to the Commission’s proposal[4].

Once a final parliament position on the DMA is in place, negotiations between the Council and the Parliament on a final text can start. The French presidency of the Council of the EU in the first half of 2022 is pushing for approval of the final DMA regulation during its term. The success of the negotiations will also depend on agreement on which companies should be considered gatekeepers (other topics are also being extensively debated – for example, the extent of participation of National Competition Authorities – but we do not consider them here).

What the data tells us

Table 3 shows our best guess at which companies could be captured under each of the four gatekeeper definitions in Table 2, when taking into account market capitalisation, turnover and number of core platform services provided. Data on the number of users for the European Union/EEA is still hard to find, which is why this criterion was not included in our analysis. Nonetheless, the thresholds for the number of end and business users are relatively similar across definitions, which allows for a sound comparison.

Of the 22 selected tech firms, 13 would fall within scope under all the four options. The ‘GAFAM’ (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft) are always classified as gatekeepers, while others are excluded in all cases either because of the non-provision of CPS (Netflix, Spotify) or non-fulfilment of criterion (a). Nine firms would be treated differently under at least one of the options. The European Commission’s originally proposed DMA would include more firms as gatekeepers (15), followed by the Council (13), then the IMCO position (12) and finally Schwab’s proposal (7)[5]. The latter would leave out companies mostly because they provide only one CPS, but there is also a case (Vivendi) in which the reason for exclusion would be the high thresholds of criterion (a)[6].

Given the cumulative nature of the three quantitative criteria, from this baseline scenario, the number of firms actually falling under the gatekeeper designation could only decrease. However, as technology companies develop and grow, more of them could be subject to the DMA obligations. Firms such as Airbnb, Zoom or Zalando could soon achieve the thresholds under the stricter IMCO position if the current trend continues.The choice between one or two CPS as a requirement to identify a gatekeeper would make a big difference to the DMA scope. While the European Commission proposes that the number of business and end-users is calculated for a CPS of the provider, Schwab’s proposal suggested that these figures should be calculated for each CPS of a provider that provides at least two of the services listed in the CPS definition. This is a crucial difference that has the power to change significantly the number of entities considered as gatekeepers. This is because many companies that provide digital services – apart from the ‘GAFAM’ – do so for one type of service. This would be the case for SAP, Oracle, Airbnb and Salesforce, for example, as Table 4 shows.

Recommended citation:

Mariniello, M. and C. Martins (2021) ‘Which platforms will be caught by the Digital Markets Act? The ‘gatekeeper’ dilemma’, Bruegel Blog, 14 December

[1] Total revenues, Free cash flow, Cash and cash equivalents, Equity, Market Capitalization end of year, Net profits, Number of employees, Investment in Plant, Property and Equipment, R&D Investments, Aggregated number of acquisitions in the last five years, Aggregated number of patents in the last two years, Number of sectors where company is active, Revenue market share (of primary market), Search traffic, Daily page views per visitor, Alexa Rank 90 Day Trend, Global active users, Business area rank score

[2] Alphabet, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Yahoo (Verizon), Twitter, Zalando, eBay, Spotify, Netflix, SAP, Slack, Schibsted, Vivendi, Booking Holdings Inc, Otto Group, Expedia, Salesforce

[3] The questions are the following: Does the platform have exclusive access to a large body of consumers?, Is it difficult for users to multi-home or switch platforms?, Are sellers substitutable?, Do users benefit from network effects requiring sellers to multi-home across platforms?, Platform has an established network, so that network effects and/or its ecosystem and related “stickiness” are an effective barrier to entry for alternative platforms.

[4] The Council proposes that the EEA turnover above or equal to €6.5 billion should be verified in each of the last three financial years, and adds that the thresholds for the number of users, both end-users and business users, should be equal to or above – instead of just above – the respective thresholds included in the Commission proposal.

[5] The outcome of our analysis is influenced by the Covid-19 pandemic crisis and its effect on the selected firms since we used the latest data available. This point is particularly relevant for the Council of the EU proposal because the threshold on turnover needs to be met for each of the last 3 financial years.

[6] This analysis is subject to limitations, given that it is still challenging to isolate data for EEA turnover, but we believe that this does not influence the accuracy of the results. Naturally, other firms could be eligible as gatekeepers since the list of firms selected for this analysis is not fully encompassing. We included firms which have been considered in the European Commission’s analysis, academic studies and mentioned in the media.