Manufacturing in the US: Will Trump’s strategy repatriate highly-paid jobs?

Trump has set out a plan to repatriate highly-paid manufacturing jobs to the US. But the idea that manufacturing jobs are better paid than service rol

Incoming US president Donald Trump has been running on a political ticket to re-negotiate trade deals. He has been promising “fairer” deals that would reduce US trade deficits and preserve well-paid manufacturing jobs.

Two of Trump’s closest advisors, Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross, will hold key positions in the new administration. They spelled out their economic policy vision in a document published on September 29 on Trump’s website, entitled “Scoring the Trump economic plan: trade, regulatory, & energy policy impacts”. Much has been said about this document already. Former US treasury secretary Larry Summers has called it “ well beyond Voodoo economics”.

One of the central claims in the paper is that trade deals have allowed companies to relocate factories away from the US, thereby leaving “Mr and Ms America …back home without high-paying jobs” (p 4). The basic contention is that “bad” trade deals lead to trade deficits, which in turn reduce the size of the manufacturing sector and leave US workers only with lower-paid service sector jobs. The authors explicitly claim that “service sector jobs tend to be of lower pay” (p9).

For wonks: if a sector has higher productivity growth and preferences are normal, a simple model shows that the share of that sector in the economy’s total employment will fall. This is also the reason why employment in agricultural sector has fallen so dramatically.

It is true that in a simple economic model with a tradable sector, call it manufacturing, and a non-tradable sector, call it services, a higher trade deficit will tend to mean less domestic manufacturing and more service sector employment (see this short graphical analysis by Paul Krugman). Of course, technological progress has been a major driver of losses in manufacturing jobs in the US and elsewhere. Nevertheless, there is truth in the claim that trade policy affects the number of jobs in manufacturing.

But is it really true that service sector jobs are worse paid than manufacturing jobs?

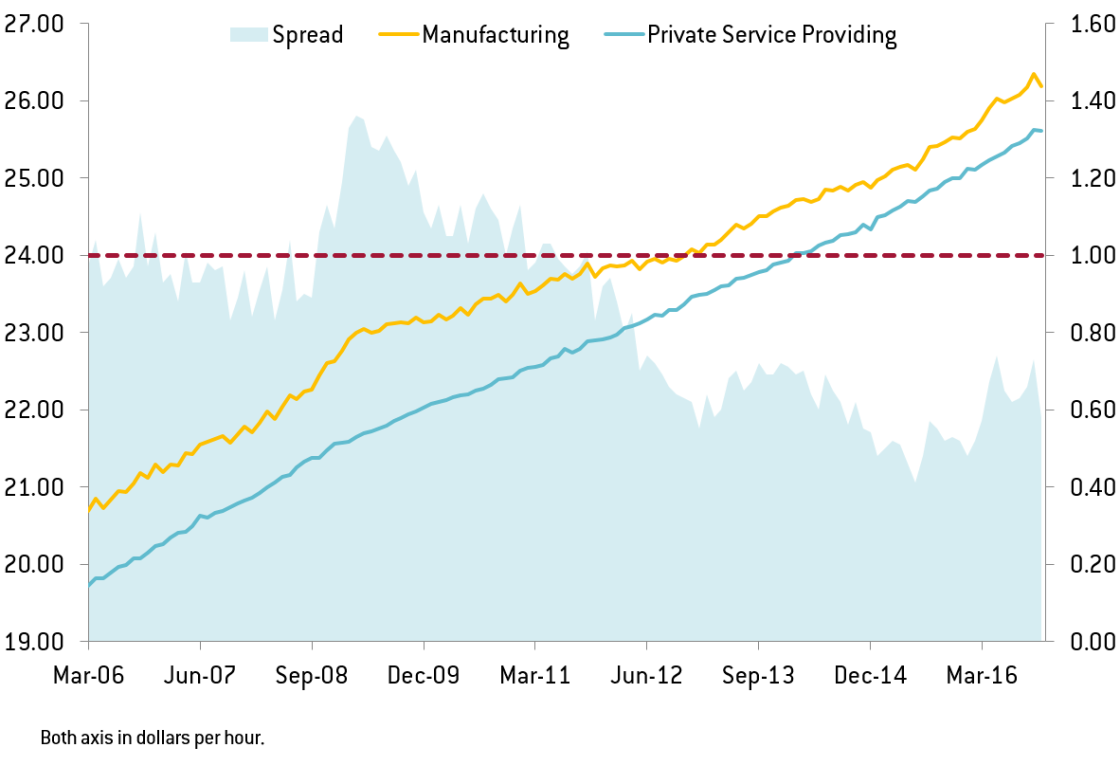

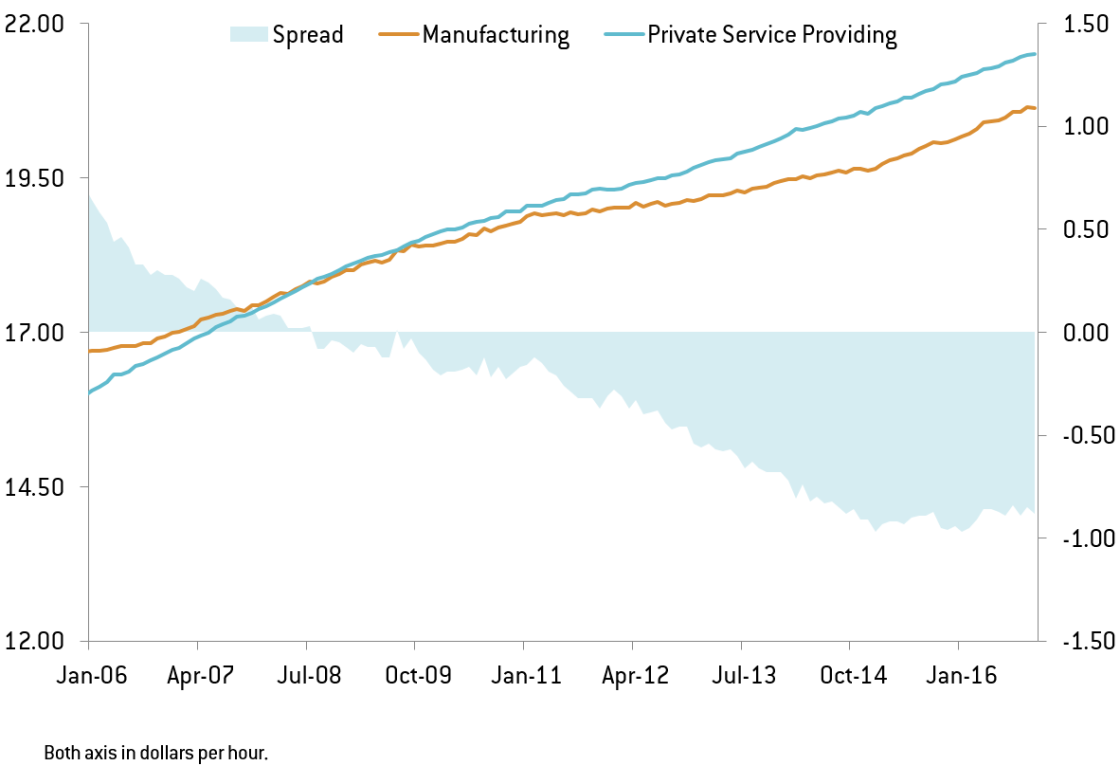

In figures 1a and b, I show the evolution of average hourly earnings in the US. The difference between the two has been falling substantially and is now at less than 80 cents per hour, that is about 3% - a rather small difference. When one takes out supervisory roles (see figure 1b) and focuses on just the “ordinary” worker/service provider, then the difference actually becomes negative and service sector jobs are better paid on average than manufacturing jobs. By about 80 cents an hour.

Figure 1a - Average hourly earnings, Dollars per hour, all employees

Note: Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted - All Employees

Source: FRED.

Figure 1b – average hourly earnings, Dollars per hour, production and non-supervisory employees

Note: Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted - Production and Nonsupervisory Employees

Source: FRED.

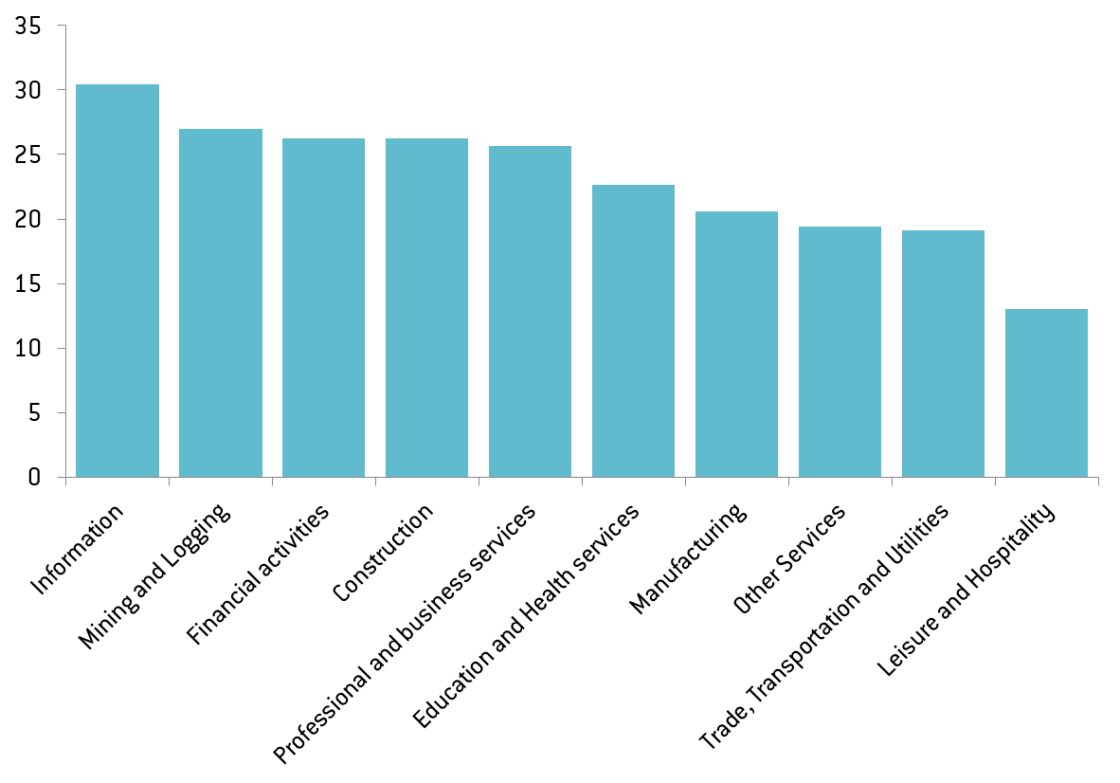

Figure 2 compares hourly earnings in different sectors of the US economy. The traditional manufacturing sector does not rank among the most highly paying sectors.

Figure 2 - average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees by sector in November 2016, Dollars per hour, seasonally adjusted

Source: FRED.

For wonks, the Balassa Samuelson theorem starts from this assumption to explain why more developed countries tend to have higher price levels.

To an economist, these results are hardly surprising. In an integrated labour market, economic theory would predict a certain convergence in wage levels across sectors to the extent that employees will tend to move to sectors with higher compensation, thereby contributing to wage level convergence.

So what effect would a systematic policy forcing companies to repatriate their factories to the US have?

What would happen if manufacturing companies followed the example of Ford and brought their production back to the US? There are two potential scenarios:

- If the US were not to impose tariffs on foreign competitors, American consumers would quickly shift to buying Volkswagens built in Mexico rather than Fords built in the US. This would be inevitable, because the price of Fords produced at American wage levels would be higher than those of Volkswagens produced at Mexican wage levels. Ford might then soon have to scale back production significantly, leading to job losses.

- Of course, the incoming President could decide to increase tariffs to protect American production. This is, in fact, what Trump’s recent Tweet regarding Toyota Motor suggests will be his future policy. In that case, American consumers would have no choice but to buy more expensive American-produced cars and bear the additional cost. In turn, they would tend to suppress their consumption of American services. Wage levels in the manufacturing sector could rise but that would only attract more people to move into these sectors, possibly eliminating the wage advantages again. The bottom line would be less consumption overall and reduced welfare as the US foregoes the benefits of specialisation that trade brings.

This analysis does not even consider possible retaliation measures by trading partners that may penalise products exported from the US, which could have negative impacts on the US manufacturing base.

What is more, there is an important political economy dimension to all of this: workers cannot move from one sector to another without difficulty. To a worker that has lost their manufacturing job in Detroit, a trade policy aimed at bringing back manufacturing jobs is good news. But if others in services lose their jobs, they do not stand to benefit.

Not only is it simply wrong to claim that any manufacturing jobs gained through a more aggressive trade policy would definitely offer higher salaries than the service sector jobs lost, as the data above clearly shows. It is also not the case that displaced service workers would simply be able to take up any additional manufacturing jobs instantly. A server cannot leave the restaurant on Friday and start to build cars on Monday.

A more sophisticated argument is that the speed with which economies were opened to major players like China may have been too fast. A recent paper by Autor et al points out that trade induces rapid change to which labour markets cannot easily adjust. Opening up too quickly to trade with competitive partners like China may therefore not be an optimal strategy. But it is still hard to see how putting up barriers after the fact would be a winning policy for Trump’s America.

So, on the whole, Trump’s strategy looks like a losing proposition – contrary to his advisors’ claims. It might mean more manufacturing jobs, so long as partners do not engage in a trade war, but those jobs would not actually be better paid and service-sector Americans would struggle to take them up anyway.