The Russian war economy: macroeconomic performance

The Russian economy has performed better than many expected since the war in Ukraine started, though the financial burden will be felt for some time.

When Russia started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the United States, European Union, several other G7 economies and their allies responded with an unprecedented package of economic, financial, diplomatic and other sanctions, which were continuously amended in the subsequent months 1 For a summary see Richard Martin, ‘Sanctions against Russia – a timeline’, S&P Global Market Intelligence, 5 July 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-new…. .

Many expected that the economic price for Russia of the aggression and sanctions would be immediate and painful 2 See for example Brian O’Toole, Daniel Fried and Edward Fishman, ‘For Biden, wreaking havoc on Russia’s economy is the least bad option’, New Atlanticist, 8 February 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/for-biden-wreakin…. . The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development in March 2022 (EBRD, 2022) forecasted a real GDP decline of 10 percent in 2022, while the International Monetary Fund in April 2022 (IMF, 2022) projected a decrease of 8.5 percent. Also according to the IMF (2022), Russia’s inflation would amount to 24 percent in December 2022 and the unemployment rate to 9.3 percent of the total labour force. Even the Bank of Russia at the end of April 2022 expected a real GDP decline of 8-10 percent in 2022 3 See http://www.cbr.ru/collection/collection/file/40964/forecast_220429.pdf. .

But the actual figures for 2022 were better (Table 1). According to the IMF, Russia’s real GDP declined by 2.1 percent in 2022. The Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) agreed 4 See https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/VVP_god_s_1995-2022.xls. We use data published by Rosstat, Bank of Russia, Russia’s finance ministry and the IMF, along with independent estimates. So far, official Russian statistics, although less detailed than those before February 2022, remains broadly in line with independent and external estimates. Instances of data discrepancy or information gaps are noted in the text. . The largest GDP decline was recorded in the second quarter of 2022, by 4.5 percent compared to the second quarter of 2021 5 See https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/VDS_kvartal_OKVED2_s2011.xlsx. . In the subsequent quarters, GDP has recovered slowly but steadily.

There were no significant changes in the sectoral structure of gross value added compared to 2021, except for mineral production, the share of which increased from 13.1 percent in 2021 to 14 percent in 2022.

The volume of goods and services exports decreased by 8.7 percent year-on-year, while imports diminished even more (by 15 percent y/y). A smaller decline in GDP means the Russian economy became more closed to the external world.

The unemployment rate reached the lowest level in the post-Soviet era, 3.9 percent (Table 1). Mobilisation of more than 300,000 men to the army from September 2022, and emigration of 300,000-600,000 people in 2022, led to a reduction in the labour force of 1.0-1.5 percent year-on-year (Abramov et al, 2023). As a result, the labour market situation became more tense for employers.

The real disposable money income of the population in 2022 decreased by 1 percent compared to 2021, ie less than during the previous crisis episodes (2008-2009, 2014-2015, 2020).

Better-than-expected results in 2022 can be attributed to several factors including conservative monetary and fiscal policies before February 2022 (Dabrowski, 2023), a well-calibrated monetary and fiscal policy reaction to the new situation, high global hydrocarbon prices and late and incomplete geographical adoption of oil sanctions.

Macroeconomic management

The beginning of the aggression against Ukraine and the first wave of financial sanctions which immobilised approximately half of Russia's international reserves (around $300 billion) and which cut off part of the Russian banking sector from the SWIFT 6 Véron and Kirschenbaum (2022). In the subsequent sanction packages, the number of sanctioned banks increased. , generated a mass capital outflow. The ruble plummeted to the lowest level in its history (120 RUB for $1) on 11 March 2022 (Figure 1). The Russian government and the Bank of Russia introduced capital and current account transaction restrictions to stop the panic (Astrov et al, 2022). Simultaneously, the Bank of Russia hiked its key policy interest rate to 20 percent (Figure 2).

These measures helped to stabilise the situation in the forex market. The official exchange rate of the ruble recovered very quickly (Figure 1) to 51 rubles to the dollar at the end of June 2022. The market exchange rate also strengthened, although it was less favourable than the official rate because of convertibility restrictions.

Quick stabilisation of the ruble allowed for the arresting of the potential inflationary impact of exchange-rate depreciation. According to IMF estimates, annual inflation increased to 12.4 percent in December 2023 (Table 1). Looking at the monthly figures of the Bank of Russia (which differ from the IMF estimates), 12-month inflation peaked at 17.8 percent in April 2022 (as a result of the ruble depreciation in February and March 2022) 7 See http://www.cbr.ru/hd_base/infl/. . Then it decreased gradually to 11.9 percent in December 2022 and a record-low level of 2.3 percent in April 2023.

The stabilisation of exchange rates also allowed for a gradual decrease in the Bank of Russia’s interest rate (Figure 2) and a relaxation of convertibility restrictions, especially for Russian residents and non-residents of the so-called friendly countries (those that have not adopted sanctions against Russia).

However, convertibility restrictions did not stop capital outflows in 2022. Although the Bank of Russia has discontinued publication of net private capital flows statistics, some trends can be deduced from the available balance-of-payments statistics 8 See http://www.cbr.ru/vfs/eng/statistics/credit_statistics/bop/bal_of_payme…. . The net capital outflow in 2022 amounted to $230.3 billion, of which $26.9 billion can be attributed to direct investment, $23.2 billion to portfolio investment, and $190.9 to other investments (but 72.6 percent of this amount left Russia in the first half of 2022). A negative capital account balance was also indirectly confirmed by the decreasing international reserves of the Bank of Russia (Figure 3).

Hydrocarbon boom and its macroeconomic consequences

Another factor contributing to better-than-expected results in 2022 was high hydrocarbon prices.

Oil prices have increased since April 2020, when they reached their COVID-19-related bottom (below $20 per barrel). In June 2021, they crossed $60 per barrel. The post-pandemic global recovery and overheating of the world economy pushed oil prices further up. The Russian invasion of Ukraine added to this trend due to a higher perception of security risks and expectations of the Western sanctions against Russia. Unsurprisingly, Brent oil prices peaked on 28 February 2022 (over $110 per barrel) and again (close to $120) on 8 June 2022.

Russia benefited from this situation. The record high current account surplus in 2022 (Table 1), particularly in the year’s first half, resulted primarily from favourable oil prices. Drastic import reductions (see above) also had an impact, partly neutralising the negative effect of freezing half of the Russian international reserves.

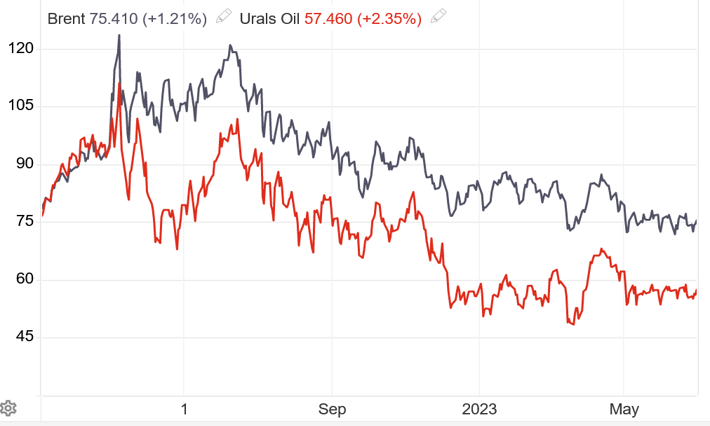

Figure 4: Brent and Urals oil prices, in $ per barrel, 01 January 2022 to 30 June 2023

Source: Trading Economics.

The increase in natural gas prices, another essential Russian export item, was even more rapid (Figure 5). However, Russia drastically reduced the volume of exported natural gas to the EU as a retaliatory measure for its support to Ukraine 9 See the Bruegel European natural gas imports tracker, https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-natural-gas-imports. . The attempts to redirect natural gas exports to Asia brought only partial results because of the limited capacity of gas pipelines and LNG exports. Therefore, it was a self-inflicted wound caused by Russia's counter-sanctions policy.

Late and incomplete sanctions

Macroeconomically, the most critical sanctions against Russia concerned its access to the global oil market. The United States banned imports of Russian oil immediately after the beginning of the Russian aggression. However, this ban had a limited economic impact due to the small volumes of Russian crude imported by the US. The EU, a much bigger importer, banned imports of Russian crude oil transported by sea routes only from 5 December 2022, and refined oil products from 5 February 2023. Furthermore, several large emerging-market economies (for example, China, India, Indonesia, Turkey, Brazil and South Africa) did not join Western sanctions against Russia at all, including sanctions related to oil imports. Therefore, Russia can easily circumvent oil sanctions by just redirection of oil export destinations.

The OPEC+ cartel and its leader Saudi Arabia were reluctant to expand oil-export quotas during the highest oil prices and cut them when global oil prices started declining.

Despite the geographical incomplete nature of sanctions and their late introduction, there has been a discount in the range of $15 to $30 per barrel for the Urals oil price (as compared to Brent), a phenomenon not observed before the full-scale war started. It limited the balance-of-payments surplus and federal budget proceeds from the oil exports. However, this discount has diminished since May 2023, which can suggest erosion of sanctions.

A more difficult 2023

Russia’s surprisingly good macroeconomic situation in 2022 has started to deteriorate in 2023, especially on the fiscal front. While in 2022 general government deficit (net borrowing) amounted to a moderate 2.2 percent of GDP, in 2023, it may amount to 6.2 percent of GDP (Table 1). Russian finance ministry preliminary fiscal data for the first half of 2023 10 See (in Russian) https://minfin.gov.ru/ru/press-center/?id_4=38583-predvaritelnaya_otsen…. confirms a deteriorating trend driven by declining global oil and natural gas prices and increasing costs of the war. Compared to the same period in 2022, federal budget revenue decreased by 11.7 percent. Hydrocarbon revenue declined by 47 percent, while non-hydrocarbon revenue increased by 17.8 percent. Federal expenditure increased by 19.5 percent, of which state procurement (which most likely includes purchases of military hardware and other army supplies) increased by 50.6 percent.

Still, Russia has relatively low public debt (Table 1), but its access to the international debt market has been closed by sanctions. The two remaining sources of deficit financing are the National Welfare Fund (NFW), which cumulated part of oil- and gas-related revenue in the surplus years along with Treasury bonds purchased mainly by state-owned banks.

On 1 June 2023, the total NFW assets amounted to $153 billion (8.2 percent of the forecasted GDP in 2023) 11 See https://minfin.gov.ru/common/upload/library/2023/06/main/Dannye__na_01…. . However, the liquid assets were slightly more than half of this amount. Part of the NWF assets was immobilised due to Western sanctions (together with the Bank of Russia’s international reserves); another part was invested earlier in the shares of Russian companies such as Sberbank and Aeroflot. Most of the liquid assets are held now in Chinese yuan and gold.

Deteriorating terms of trade are also seen in the balance of payments statistics. While a current account balance remains positive, its surplus is much smaller than in 2022 (Table 1). It has impacted the ruble’s exchange rate, which has depreciated since October 2022 (Figure 1). At the beginning of July 2023, it exceeded 90 ruble to the dollar. A weaker ruble may boost inflation from the current low level.

The short-term prospects (the next 12 months) for the federal budget and balance of payments will depend on oil prices that Russian exporters can effectively obtain in the international (mainly Asian) markets.

Conclusions

While the economic burden of the war and decoupling with the EU and other advanced economies will harm the growth prospects of the Russian economy in the medium-to-long term (Ribakova, 2023), adding to other negative factors including shrinking population and its ageing, the poor business climate and increasing government interventionism, they have not been lethal yet. Russia has avoided macroeconomic and financial destabilisation, minimised output losses and retained resources to continue its aggression against Ukraine.

Better-than-expected macroeconomic performance in 2022 and the first half of 2023 can be attributed to the situation on the global hydrocarbon market, favourable macroeconomic performance before the war, well-calibrated macroeconomic policy and regulatory response to sanctions, and the geographical incompleteness of those sanctions. Russia also took several preparatory steps ahead of the confrontation with the West in 2014-2022, including building an independent payment system, import substitution, developing trade relations with China and conducting conservative macroeconomic policies (Dabrowski and Avdasheva, 2023) that increased the resilience of the Russian economy to Western sanctions. On the other hand, Russian counter-sanctions against ‘unfriendly’ countries, especially those stopping natural gas exports to Europe, were self-damaging while missing their geopolitical goal of weaken the support for Ukraine provided by the EU and G7 countries.

Acknowlegements

The author would like to thank Maria Demertzis, Francesco Papadia, Elina Ribakova, Nicholas Véron and Jeromin Zettelmeyer for their comments and suggestions on a draft of this analysis.

References

Abramov, A.E., N.A. Avksent'ev, E.A. Apevalova, I. Arlashkin, M. Baeva, G. Balandina ... A. Shelepov (2023) Russian Economy in 2022, Trends and Outlooks, Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, available at https://www.iep.ru/en/publications/publication/russian-economy-in-2022-trends-and-outlooks-issue-44.html

Astrov, V., V. Inozemtsev and N. Vujanovic (2022) Monthly Report, March, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, available at https://wiiw.ac.at/monthly-report-no-03-2022-dlp-6124.pdf

Dabrowski, M. (2023) 'Macroeconomic Vulnerability, Monetary, and Fiscal Policies', in M. Dabrowski (ed) The Contemporary Russian Economy, Palgrave Macmillan

Dabrowski, M. and S. Avdasheva (2023) 'Sanctions and Forces Driving to Autarky', in M. Dabrowski (ed) The Contemporary Russian Economy, Palgrave Macmillan

EBRD (2022) 'In the shadow of the war, the economic fallout from the war on Ukraine', Regional Economic Update March 2022, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, available at https://www.ebrd.com/rep-ukraine-war-310322.pdf

IMF (2022) World Economic Outlook Database April 2022, International Monetary Fund, available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April/weo-report

Ribakova, E. (2023) 'Sanctions against Russia will worsen its already poor economic prospects', Analysis, 2 May, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/sanctions-against-russia-will-worsen-its-already-poor-economic-prospects

Véron, N. and J. Kirschenbaum (2022) ‘The European Union should sanction Sberbank and other Russian banks’, Bruegel Blog, 15 April, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/european-union-should-sanction-sberbank-and-other-russian-banks