How Europe could yet take the lead in the global electric-vehicle development race

The electrification of vehicles has become a key trend in the automotive sector, driven by clean energy and climate-change concerns. In a scenario of

The automotive sector is important for the EU economy. Accounting for 4% of EU GDP, it employs 8 million people and ranks among the main EU sectors in terms of exports and research and development (R&D). And because of its long supply chain, the sector has a significant multiplier effect on the EU economy.

The automotive sector is currently at the centre of a global transformation, driven by four key trends: electrification, autonomous driving, sharing, and connected cars. While each of these interconnected trends is already visible in daily life, their full deployment is not yet guaranteed, nor is the speed of take-up.

The electrification of vehicles has become a key trend in the automotive sector, driven by clean energy and climate-change concerns and policy interventions – such as support for zero-emission vehicles and carbon taxes – intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We can expect EVs to proliferate in the future. On the technology side, improvements are quickly reducing electric-vehicle (EV) production costs, in particular by reducing battery costs. On the policy side, to meet commitments assumed under the Paris Agreement, more governments are increasing their support for zero-emission vehicles, banning dirty vehicles and supporting the deployment of EVs and their charging infrastructure.

In a recent Policy Contribution we investigated the position of the European automotive industry in a scenario in which electrification substantially progresses. In this blog post we summarise the results of our study, which are – surprisingly – encouraging for Europe.

Electric vehicles in Europe: the demand side

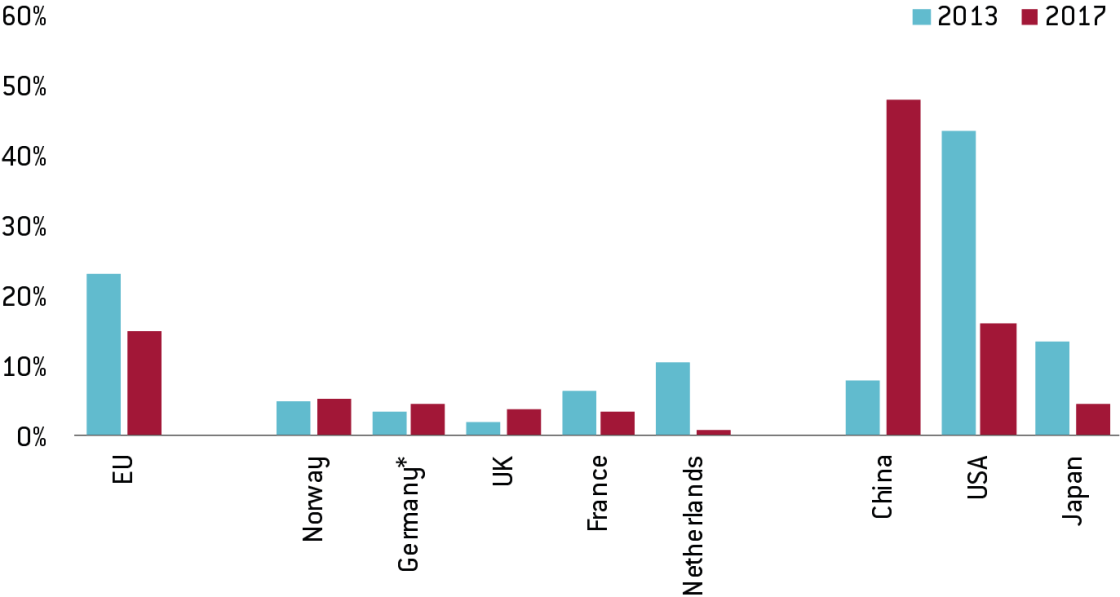

Data on registrations of electric vehicles reveals that the global EV market remains, to date, still a small part of the overall car market. In all major countries, EVs in 2017 had shares well below 5% of total vehicle registrations. But it is growing rapidly. This growth is particularly manifesting itself in China. As a consequence, the major market for electric vehicles is nowadays in China. While the EU (with 23%) and the US (with 48%) dominated the worldwide EV market in 2013, by 2017 China had a clear lead, with 48% of global EV registration, leaving far behind the US (with 16%) and the EU28 (with 15%). Within the EU, Germany and the UK increased their shares of the global EV market, while France and early-adopter the Netherlands experienced declines between 2013 and 2017 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of new EV registrations of country in world new EV registrations

Source: Bruegel based on national statistics.

Electric vehicles in Europe: the supply side

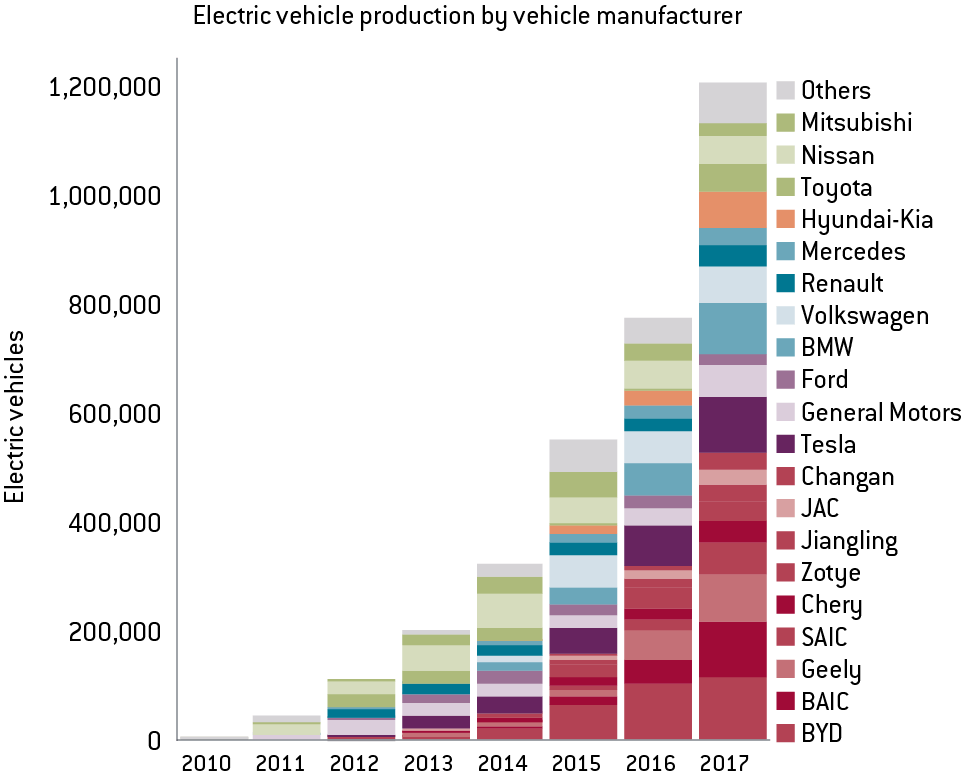

China is also the source of another crucial trend in global EV manufacturing: over the last few years, it has rapidly established itself as the global leader, leaving Europe and other regions behind. While Japanese and US firms were early movers, nowadays the largest EV manufacturers are new Chinese firms (Figure 2, left panel). From the early movers, only US’s Tesla is currently a leading manufacturer in the global EV market. EU firms entered late, and are only recently starting their catching up, especially the Germans.

Figure 2: EV production by vehicle manufacturer and by battery manufacturer

Source: International Council on Clean Transport (2018).

In global EV battery manufacturing (Figure 2, right panel), which is a crucial part of the EV value chain, China’s leadership is even more evident. The first mover, Japan, was rapidly surpassed by China between 2014 and 2017, as Chinese companies proliferated and grew rapidly along with Korean firms. There are no EU or US firms among the world’s major battery producers.

This impressive rise of China in EV manufacturing has been driven by the country’s strong industrial policy in the field (e.g. generous fiscal subsidies for EV manufacturers, based on the EV’s driving range per charge, to foster innovation; requirements for international carmakers to manufacture EVs in China in order to access the market; strong financial incentives for EV purchasers; extensive charging infrastructure deployment).

EU and the technology development in EVs

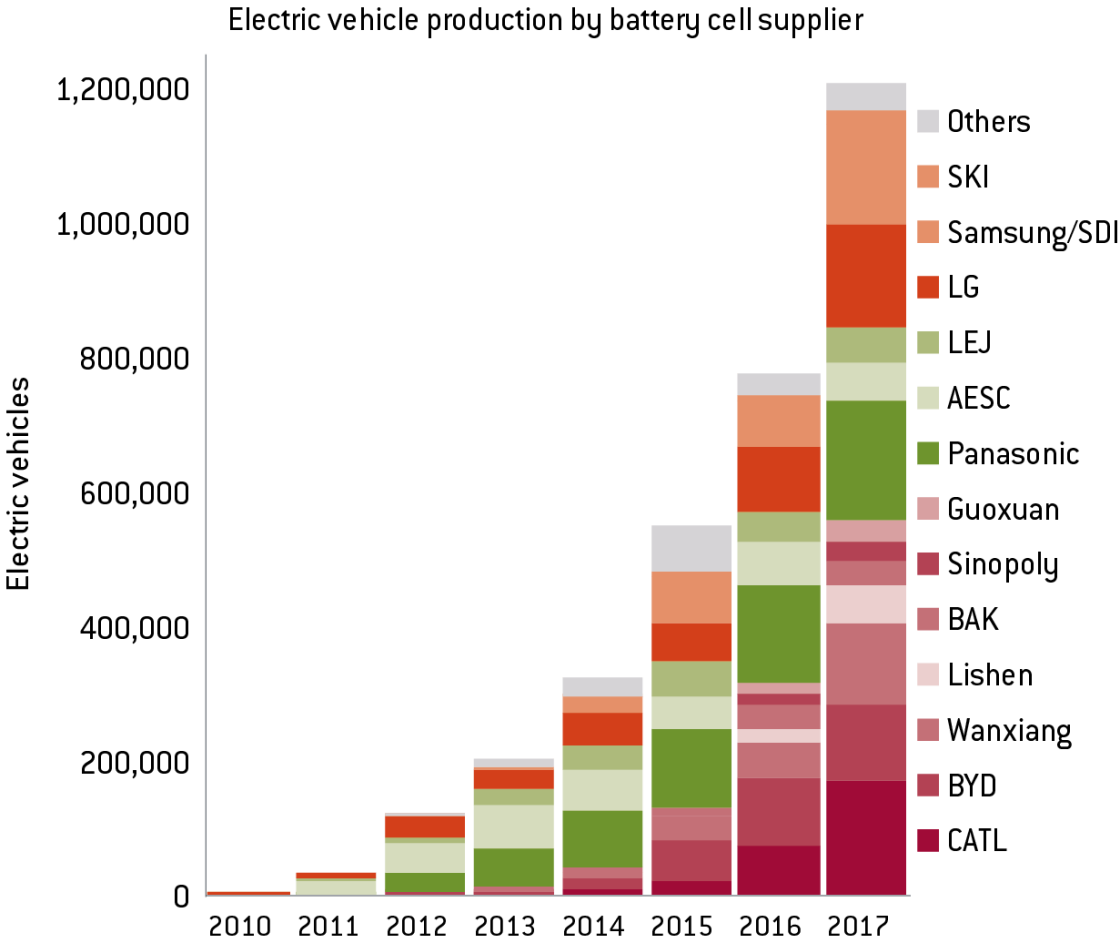

The EU was not a first mover neither in EV technology development, as patent data show. The Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) technology has traditionally been the major power train technology for cars. The EU dominated the ICE technology until 2008. EV technology patenting activity, while mostly flat until 2005, kick-started globally in 2005. In the EU it began to grow only in 2009 (Figure 3).

The dominance of ICE technology in EU automotive patents before 2009 has since been changed to a more balanced position across all power-train technologies – electric, hybrid, hydrogen and ICE. For instance, the number of EU EV patents grew from 124 in 2008 to more than 250 per year for each year between 2011-2016.

Figure 3: EU vs. rest of the world in major power-train technology patents

Source: Bruegel based on EPO Patstat, April 2018 edition.

How European automotive firms tackle the EV challenge

Which EU automotive firms are driving the EV trends? Although they were not the first movers on EVs, European automotive firms have now all become as buoyant on the EV market as their global counterparts. All have announced new EV models and ambitious annual EV sales targets to be achieved in the near future.

But as most of the investment in EVs are still very recent and/or attached to announced plans, hard evidence of actual committed investment by EU firms in EV manufacturing is not widely available.

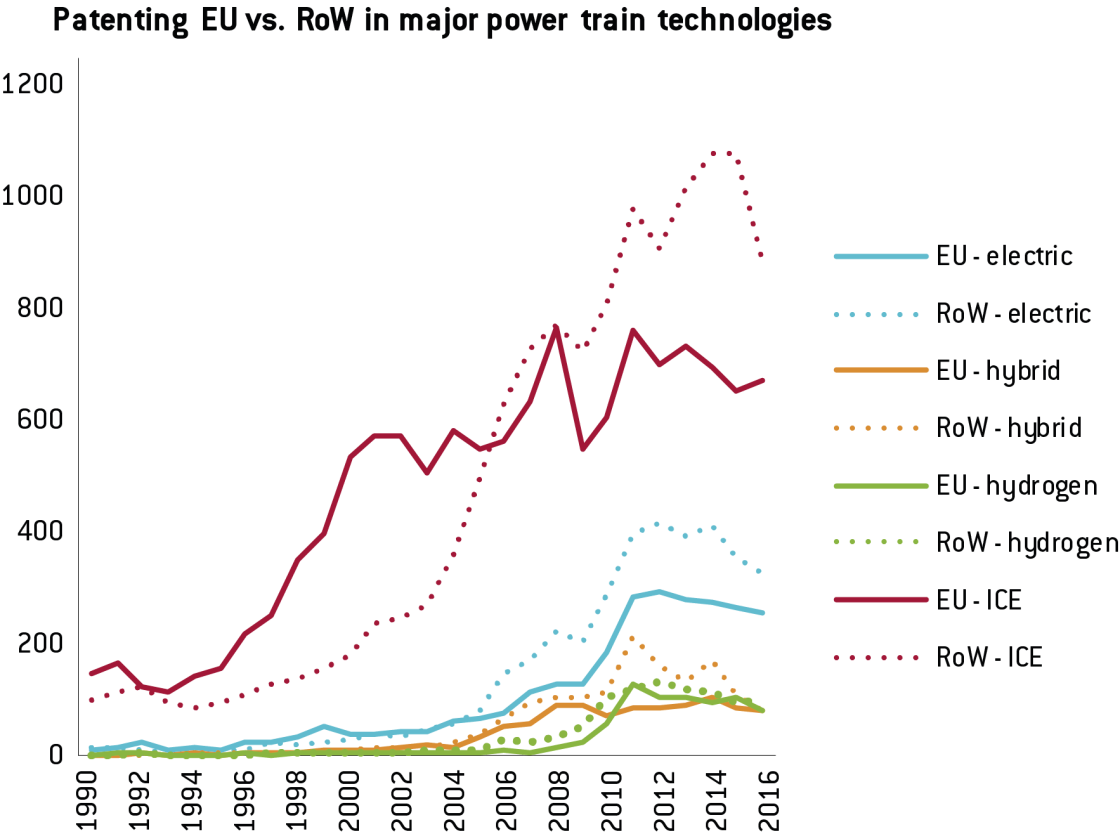

In order to assess the commitment of EU firms to EV technology, we turn to patent statistics to assess how active EU automotive firms have been in developing EV technology compared to their international competitors and compared to their activities in improving the incumbent ICE technology.

The gap in policy ambition between Europe and China is huge.

We focus on the automotive and parts firms who are the largest R&D spending firms in the world, as recorded by the EC-JRC Scoreboard. This handful of large firms account for the overwhelming majority of patenting activities in this sector. Patenting by South Korea’s automotive sector is dominated by Hyundai; in the US it is General Motors and Ford. The EU and Japan, although they have big players such as Volkswagen and Toyota, show a more distributed structure of patenting activity with several major players involved. In all cases, all of the major players are established incumbents, with very few new entrants, Tesla and Chinese companies being the exception.

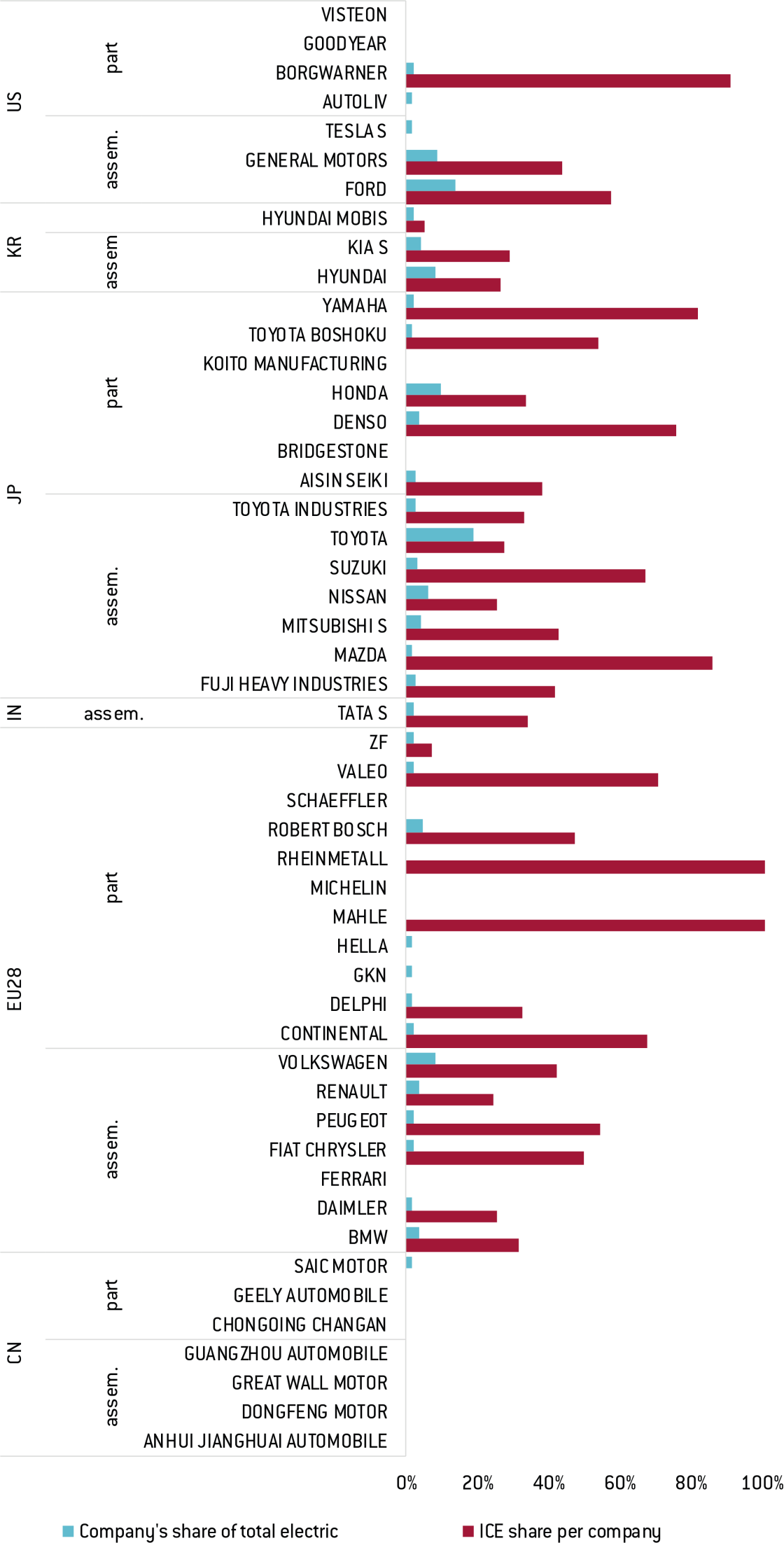

There are major differences between the patenting activities of different companies (Figure 4). Chinese companies exhibit an overall still very low level of patenting. Among the EU assembly companies, Renault, BMW and Volkswagen have the highest shares of electric power-train technology patents, while also having large shares of ICE patents. Overall, these EU assembly companies exhibit relatively balanced patenting activity. This contrasts with EU automotive parts companies, which exhibit a much greater degree of specialisation when it comes to power-train technologies. Some companies, such as Mahle and Rheinmetall, are active only in ICE technology patenting. Other car parts companies have higher shares of non-ICE patenting, though with low absolute numbers. The balanced patenting activity is also true for the Japanese and US incumbent automotive assemblers.

Figure 4: Patenting structure of the top 50 R&D spending automotive companies (2012-14)

Source: Bruegel on JRC Scoreboard 2016.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The transition to zero-emission transport and the development clean power-train technologies as alternatives to the ICE, among which the EV technology is the most powerful, needs to be supported by a more ambitious and broader policy agenda both at the EU and at member-state level. It is not too late for Europe to lead the global EV race, but it has to step up if it wants to remain at the frontier of automotive technology.

It is for the EU automotive industry to face and ideally drive the global EV revolution and to take up pivotal positions in the EV value chain. As EU companies were not among the EV first-movers, they will have to invest more ambitiously in new EV technologies, while more quickly reducing their exposure to the incumbent ICE technology. Too many important companies, especially car-parts manufacturers, are still predominantly or even exclusively focused on ICE technologies. The EU particularly lacks strong players that can capture the value from batteries for EVs.

European firms have the capacity to continue their global leadership of the automotive sector as the next generation of automotive technologies is phased in. European car and car parts manufacturers can rely on a large internal market, a long experience and a strong brand-name in automotive manufacturing. They also have the technological expertise from a portfolio of R&D projects and patents that is diversified across various power-train technologies. But in order to realise the potential from this capacity, and to face global and particularly Chinese competition, European firms will have to be more ambitious.

To warrant more ambitious investment in EVs by EU automotive companies, the proper framework conditions should be in place. Both the EU and EU member states are increasingly discussing and putting in place policies to support the deployment of EVs. However, best-practice examples of EV policies from Norway and China illustrate that piecemeal interventions will not work. What is needed is a broad policy framework, combining a multitude of demand- and supply-side instruments in an ambitious long-term clean transport policy mix.

First and foremost, there needs to be EU demand for EVs. Subsidies, taxation and public procurement favouring clean rather than dirty technologies should be used to stimulate EU demand for clean technologies in general, including EVs. Without an EU internal market for EVs, EU companies might be developing their ambitious investments in other world regions, most notably China. On the supply side, the policy menu includes public R&D support for the next generation of clean technologies, including support for investment in the latest and next-generation clean technologies, and support for the conversion of dirty technologies into clean. Policymakers can also favour clean technologies that include EVs by establishing efficiency standards. Last but not least, a full range of policies can be implemented to bolster infrastructure deployment: a non-exhaustive list includes urban planning, public transport, charging stations and accessibility improvements.

The gap in policy ambition between Europe and China is huge. The Chinese EV policy mix includes strong commitments to an electric future and coercive measures for carmakers. Europe cannot follow China in the adoption of centrally-planned industrial policy measures. However, Europe can and should do more to stimulate the transformation of its automotive industry through a more ambitious combination of supply and demand-stimulating policy measures. At the EU level, this includes particularly:

1) Targeting EU R&D funds to trigger frontier clean technologies

The EU can improve its transport research and innovation funding. In particular, it should carefully allocate this money, targeting areas in which it can truly have leverage on private investment. Transport-related research and innovation funding should notably focus on next-generation early-phase technologies and should focus across the value chain, including for next-generation batteries, such as solid-state batteries.

2) Rethinking transport taxation

Taxation is a key policy tool to switch demand to cleaner transport, fostering road transport decarbonisation. European countries still have very different transport taxation regimes. The EU should promote a new discussion among EU countries on the future of transport taxation, as is being done in the field of digital taxation. A harmonisation of mobility taxation throughout Europe would lead to less fragmentation and more certainty for business, thus increasing the incentives to invest in production of clean (electric) vehicles in Europe.

3) Bans on dirty cars: cleaning-up the air

Since 2017, a series of countries and cities across Europe have introduced bans on diesel and petrol cars. These plans are mainly driven by a political commitment to reduce air pollution, and are based on the expectation that the shift already under way towards clean vehicles will continue to gather pace over the coming years. These plans are also meant to provide a strong signal to the EU automotive industry, encouraging it to innovate and become a global player in clean vehicles. The EU should ensure that these plans should be more coordinated and ambitious.

4) EU support for member states’ transition towards clean transport

To encourage its member states and cities to clean-up their transport systems, the EU should support the transition costs associated with this transformation. An ‘EU Clean Transport Fund’ could be established to provide dedicated financial support to countries and cities committed to a transformation to decarbonise transport. For instance, this fund could allow cities to bid for EU money to support measures such as the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructure or to support the retraining of automotive workers to enable them to switch from dirty to clean technology production technologies.