The economic effects of migration

What’s at stake: migration is currently a very hot topic in both the US and the EU. Immigration issues have come to the forefront due to the problem o

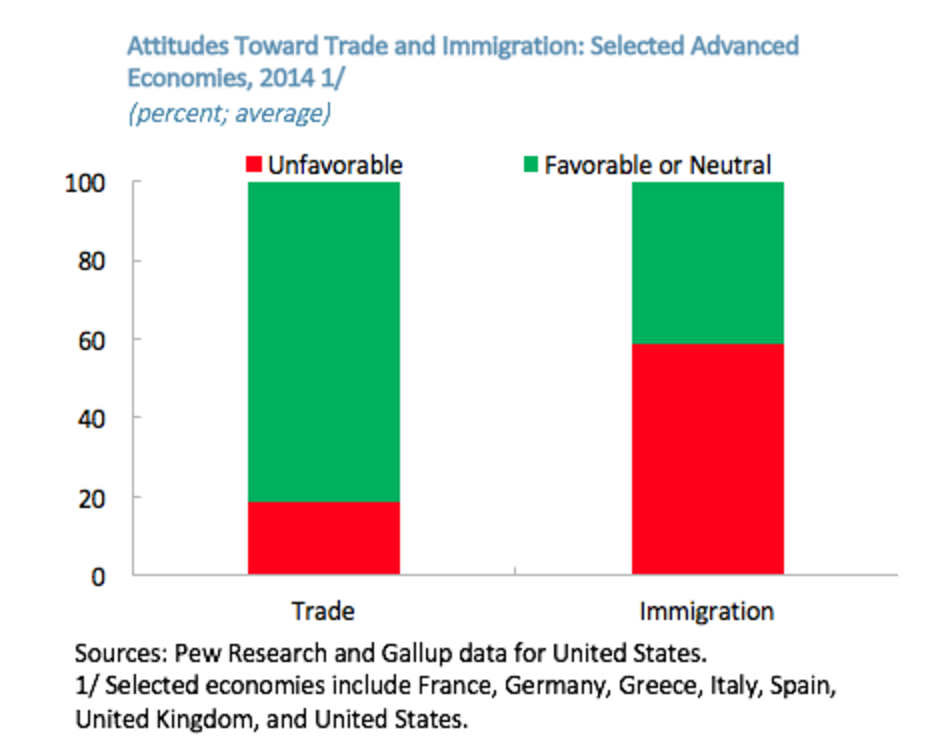

Jaumotte, Koloskova and Saxena at the IMF and VoxEU argue that migration, no matter how controversial politically (see figure 1), makes sense economically. In the long term, both high and low-skilled workers who migrate bring benefits to their new home countries by increasing income per person and living standards. High-skilled migrants bring diverse talent and expertise, while low-skilled migrants fill essential occupations for which natives are in short supply and allow natives to be employed at higher-skilled jobs. Gains are broadly shared by the population, so it may be well-worth shouldering the short-term costs to help integrate these new workers.

Figure 1

From Jaumotte et al.

Clemens and Pritchett (2016) assess the new economic case for migration restriction. Migration economics has traditionally stressed the effects of migration restrictions on income distribution in the host country. Recently the literature has taken a new direction by estimating the costs of migration restrictions to global economic efficiency. A new strand of research posits that migration restrictions could be not only desirably redistributive, but in fact globally efficient. This new case rests on the possibility that without tight restrictions on migration, migrants from poor countries could transmit low productivity to rich countries, offsetting efficiency gains from the spatial reallocation of labor from low to high-productivity places. Clemens and Pritchett provide an assessment, and conclude that the new case for efficiency-enhancing restrictions on labor mobility turns out to be an efficiency case against most existing restrictions on labor mobility. On current evidence about the magnitudes of the relevant parameters, dynamically efficient policy would not imply open borders but would imply relaxations on current restrictions.

Using immigration records from Norway, Furlanetto and Robstad argue that an increase in immigration lowers unemployment (even for native workers) and has no negative effects on public finances. However, they do identify a negative effect on productivity that may be a worry for long-term growth. The case of Norway is interesting because, while immigration was a marginal phenomenon in the 1990s, it became the dominant driver of population growth after EU enlargement to include Eastern European countries.

d’Artis Kancs and Lecca (2016) look at long-term social, economic and fiscal effects of immigration in the EU, by applying a Commission macroeconomic model to alternative refugee integration scenarios. The simulation results suggest that, although refugee integration is costly for public budgets, in the medium to long-run the social, economic and fiscal benefits may significantly outweigh the short-run integration costs. In addition, integration policy has the potential to play an important role in improving social inclusion, filling vacancies, improving the ratio of economically active to those who are inactive, addressing Europe’s demographic challenges, and boosting jobs and growth in the EU.

A multi-author report by RAND looks at the cost of non-Schengen from a civil liberties and home affairs perspective. They estimate the cost of re-introducing internal border controls in the Schengen Area at around €0.1–19bn in one-off costs - depending on the extent of border crossing point reconstruction - and around €2–4bn in annual operating costs, corresponding to around 0.02–0.03 per cent of Schengen Area GDP.

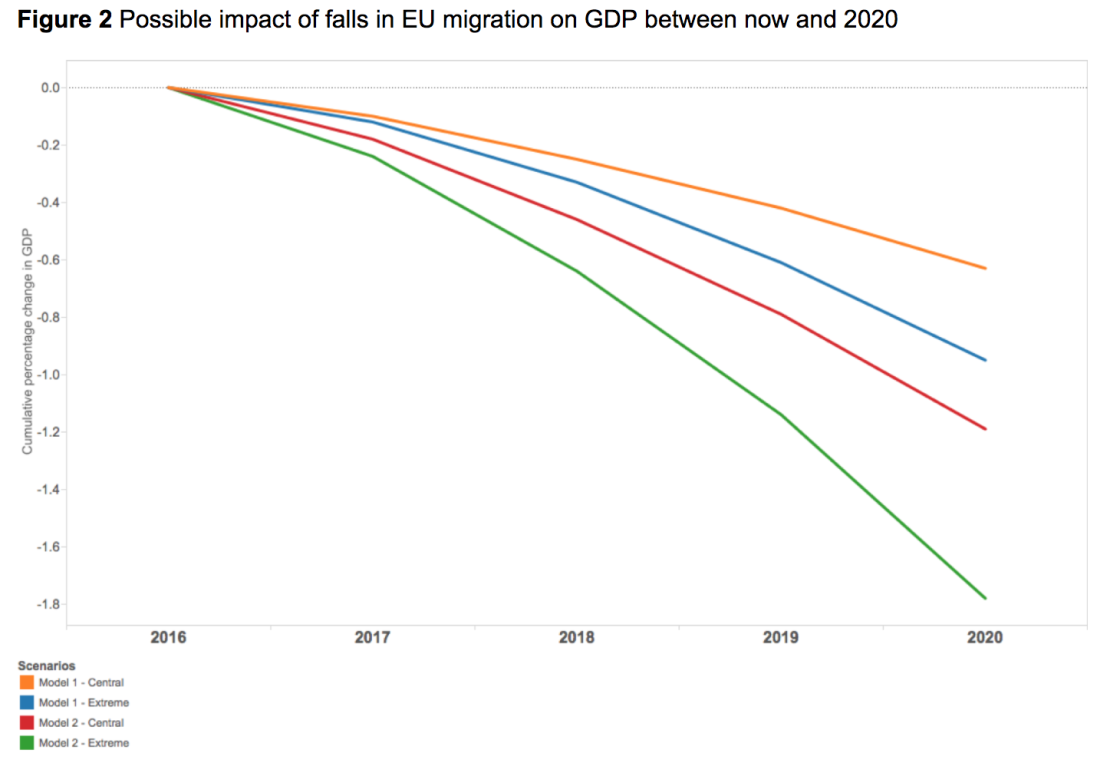

Portes and Forte look specifically at the economic impact of Brexit-induced reductions in migration. Their scenarios imply that net EU migration to the UK could fall by up to 91 000 on the central scenario, and up to 150 000 on a more extreme scenario. Using the existing empirical evidence on the impact of migration on growth and productivity in advanced economies, they estimate the possible impact of falls in EU migration on GDP and GDP per capita growth between now and 2020, compared to a counterfactual where EU migration remains constant. In their central scenario, the impact would be to reduce GDP by between about 0.63% to 1.19%, while GDP per capita would be reduced by between about 0.22% and 0.78%. In the more extreme scenario, the hit to GDP per capita would be up to 1.16%.

Burchardi et al. evaluates the causal effect of migration on foreign direct investment using immigration patterns to the US going back to the 19th century. Foreign direct investment is found to follow the paths of historical migrants as much as it follows differences in productivity, tax rates, and education. For the average US county, doubling the number of individuals with ancestry from a given origin country increases by 4 percentage points the probability that at least one firm from this US county engages in FDI with that origin country, and increases by 29% the number of local jobs at subsidiaries of firms headquartered in that origin country. Their results suggest that causality runs through a mechanism of information flow facilitation, and that the effect of ancestry on foreign direct investment is very long-lasting.

Peri (2016) argues that the economic impact of immigration on receiving economies needs to be understood by analysing the specific skills brought by immigrants. The complementarity and substitutability between immigrants and natives in employment, and the response of receiving economies in terms of specialisation and technological choices, are important when considering the general equilibrium effects of immigration. He argues that in the United States, a balanced composition of immigrants between college and noncollege educated, together with the adjustment of demand and technology, imply that general equilibrium effects on relative and absolute wages have been small.

George Borjas estimates that the presence of immigrant workers in the labor market makes the U.S. economy (GDP) an estimated 11 percent larger ($1.6 trillion) each year, but he argues that this contribution to the aggregate economy does not measure the net benefit to the native-born population because 97.8 percent of the increase in GDP goes to the immigrants themselves in the form of wages and benefits. Borjas further estimates that the net gain to natives equals just 0.2 percent of the total GDP in the United States (the “ immigrant surplus”) and that immigration reduces the wages of natives in competition with immigrants by an estimated $402 billion a year, while increasing profits or the incomes of users of immigrants by an estimated $437 billion.

A report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on the other hand find that when measured over a period of 10 years or more, the impact of immigration on the wages of native-born workers overall is very small. To the extent that negative impacts occur, they are most likely to be found for prior immigrants or native-born workers who have not completed high school. Some evidence on inflow of skilled immigrants suggests that there may be positive wage effects for some subgroups of native-born workers, and other benefits to the economy more broadly, as immigration is found to have an overall positive impact on long-run economic growth in the U.S. In terms of fiscal impacts, first-generation immigrants are more costly to governments than are the native-born. However, as adults, the children of immigrants (the second generation) are among the strongest economic and fiscal contributors in the U.S. population. Over the long term, the impacts of immigrants on government budgets are generally positive at the federal level although fiscal effects vary considerably across states.