Why is rebalancing in Europe so painfully slow?

There is growing debate about adjustments within a monetary union and the extent to which these can be engineered and accelerated. Gopinath, F

There is growing debate about adjustments within a monetary union and the extent to which these can be engineered and accelerated. Gopinath, Farhi and Itskhoki have recently rekindled the debate by showing how internal devaluations can be designed using fiscal levers. A summary of their paper is available here and the full paper is available here. It is very rigorous way of looking at how and why external rebalancing and internal devaluations work or don’t.

This is something we have looked into empirically at Bruegel where Zsolt Darvas focused especially on the adjustments in Ireland, Iceland Latvia and which resonated in the blogosphere (Krugman, Irish economy). But outside of these three countries, the adjustment quandary remains.

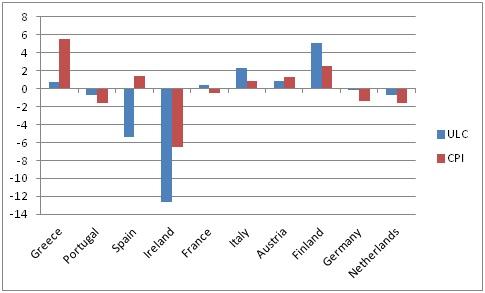

Some years ago, the European Commission estimated competitiveness adjustment needs to amount to 20 percent in terms of real effective exchange rates (see here). In year 4 of the crisis, it is time to assess how much assessment actually happened so far. To say it in a few words: not much. The following figure shows that during 2007-2011, in many countries there was no fundamental competitiveness adjustment.

Changes in Reer (Intra*) 2007-2011

Source: EUROSTAT, * Intra refers to the REER relative to 16 euro zone trading partners.

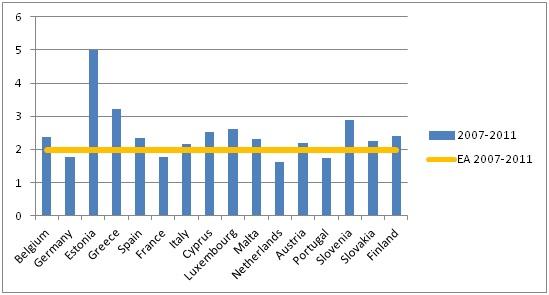

On the contrary, except for Ireland and Spain, price competitiveness really continued the old trends prior to the crisis. The same picture emerges when one looks at CPI growth. The figure below shows that during 2007-11, the reversal of inflation rates did not really happen. Ideally, one would have liked to see inflation rates in Greece, Spain and Italy to fall below the euro area average while inflation in Germany, Netherlands and Austria should move above the EA average. This has, however, not happened.

CPI growth 2007-2011

Source: EUROSTAT

So what to conclude?

- Reversing entrenched inflation trends takes a long time, especially when the winds of Balassa-Samuelson (ie. convergence) effects continue to blow.

- Even when price inflation trends adjust, the adjustment will still take very long as price inflation differentials of 1-2 percent mean that it takes 10-20 years to close a gap of 20%.

- It is therefore of key importance, that competitiveness adjustment is not only happening in terms of prices but also in terms of productivity. A productivity and growth agenda for some countries of Southern Europe is desperately needed but this is of micro than a macro story. Innovation, firm level determinants of exports, education and institutions are of key importance and need to be studied in detail. Bruegel is doing this with its research on EFIGE and on innovation.