The impact of Brexit on UK tertiary education and R&D

In this blog post, we look at the impact of Brexit on UK’s education and research and development sectors in terms of students and staff, as well as f

In an open letter signed by more than 100 heads of UK universities almost a year ago, the British academic community expressed that Brexit would be a disaster for UK science and universities.

Prime Minister Theresa May recently set out the general guidelines for leaving the EU, and possibly a sector-by sector approach to negotiations.

We find that the results on the flows of staff and student populations are not easy to predict without a clearer idea on extra requirements (e.g. visa, fees charged). However, an immediate loss from exiting the EU will be in funds for research and education — an annual amount of €1.5 billion.

Naturally, as the UK will no longer have to contribute to the EU budget, some funds will be repatriated and therefore be available. Whether they will suffice, however, depends on negotiations that will follow and the will to match this €1.5 billion annual flow from the domestic budget.

The student population

According to the latest data published by HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency), there are currently over 438,000 non-UK nationals studying in UK universities (about 20% of the total), out of which 127,000 are EU nationals. This figure slightly increased in both absolute and relative terms over the last ten years.

Furthermore, the number of new EU enrolments in UK universities has steadily increased over the years (especially from poorer European countries), reaching 31,350 new EU students in 2016. How will this number change if immigration control measures are implemented?

A recent impact assessment by London Economics for HEPI (Higher Education Policy Institute) and Kaplan International claims that the UK’s departure from the EU will have mixed effects, but overall it will have a negative impact on the British economy.

Regarding the impact of Brexit on EU student enrolments and university income, there are contradictory views. On the negative side:

- harmonising fees for EU and non-EU students (thereby increasing their fees) would reduce the number of enrolments by more than 31,000;

- if visa issues were to constrain overseas students, then the total number of enrolments would plunge further.

On the other hand:

- harmonisation between the EU and non-EU students would increase tuition income from enrolling students;

- a depreciation of the sterling would reduce the real value of fees and increase the number of enrolments from all other countries, partially offsetting the tuition effect. However, it is worth adding that only a very substantial depreciation would eliminate this effect.

By leaving the Union, the UK will also give up its access to Erasmus+, the EU’s umbrella exchange programme that brings together several funding schemes for education and training, youth and sport. In 2014, its first year, Erasmus+ allowed more than 36,000 UK students, youth workers and staff to study, train or volunteer abroad. An even greater number is estimated to have come to the UK.

On the positive side, the British themselves have a favourable view on the flow of foreign students. A poll by Universities UK based on over 2,000 British adults found that:

- three-quarters of the respondents would like to see the same number or more of international students in the UK;

- almost all agreed that they should be able to work in the UK for a period of time after completing their studies;

Only a quarter of both leave and remain voters consider international students as immigrants. With that in mind, the public is likely to support cooperative arrangements regarding students and exert pressure accordingly.

Academic and non-academic university staff

In UK universities about 30% of academic staff members are non-UK nationals. There are currently more than 33,700 academic staff members from the EU, representing about 17% of the total (excluding atypical contracts). In addition, the number of EU non-academic staff amounts to 12,500 employees, or 6% of all professional staff.

Without clear direction on how EU citizens will be dealt with after Brexit, the effects remain speculative at best. However, there are also indirect consequences that are worth considering.

Research is an increasingly collaborative sector, with internationally co-authored papers cited more frequently than papers published by only UK-based authors. More than half of UK publications are internationally co-authored, 60% of which with EU partners, and these figures are growing. According to a report by the Royal Society, it is not clear whether EU-UK collaborations depend on EU membership, but visa restrictions might negatively affect researcher mobility and more generally international research collaboration.

Prime Minister Theresa May has repeatedly claimed that the UK’s research and innovation sector will be protected and enhanced, aiming to provide reassurance and certainty to the increasingly international body of researchers residing in the UK.

Nevertheless, according to a recent survey of academics conducted by YouGov, 76% of EU (non-UK) academics are now more likely to consider leaving the UK, and 29% of all respondents know other academics that have already left. Moreover, 90% of the respondents think that Brexit will have a negative impact on UK higher education and 44% are aware of academics having lost access to EU research partnerships and funding.

Funding: can losses be recouped?

A joint submission to the UK Government from National Academies argues that research and development is one of the economic sectors to face net losses as a result of Brexit. While the UK is a net contributor to the EU budget, not all sectors benefit in the same manner.

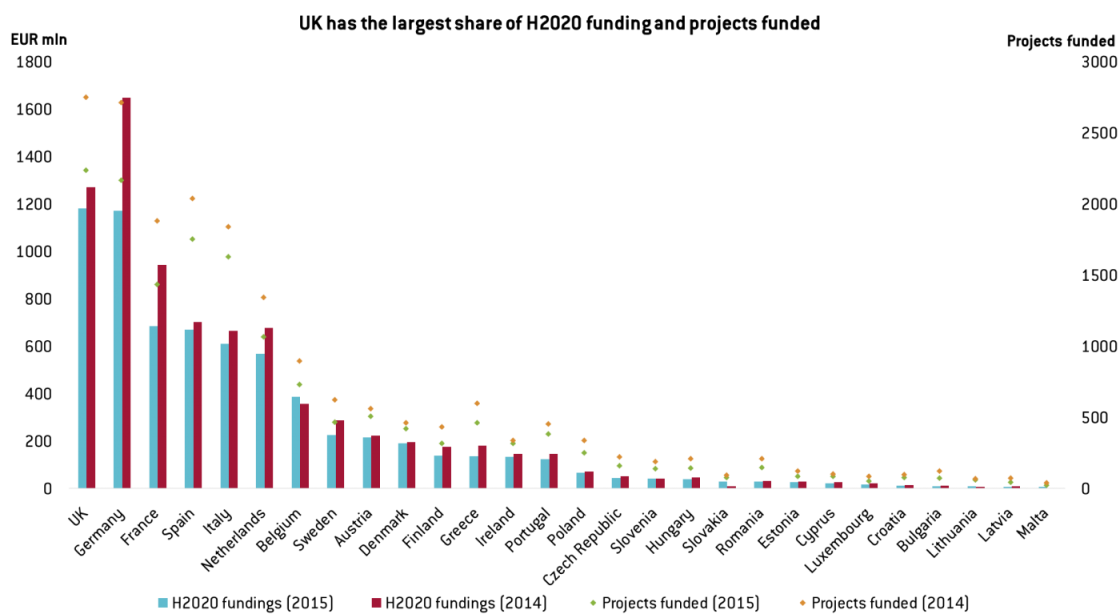

One of the main sources of funding for UK universities and research centers is Horizon 2020, the EU’s main umbrella programme for research and innovation. In recent years, researchers in UK universities have secured the largest share of total projects funded, i.e. more than 2,000 per year.

In 2015 this was equivalent to almost €1.2 billion in H2020 grants and contracts (16% of the total), more than any other EU country’s share. This amount represents 17.5% of UK’s R&D budget for 2015/16. According to the Brexit white paper, projects approved before the actual departure from the EU will continue to receive H2020 funding with the UK Treasury underwriting the payment of such grants.

Source: European Commission, Horizon 2020 Monitoring Report 2015

The UK also receives other streams of funds from the EU that relate to research and education. In 2015, €122 million have been given to UK citizens and organisations for studying, training and volunteering abroad through the Erasmus+ programme.

Furthermore, for the period between 2014 and 2020, the UK is set to receive more than €16 billion from the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF). According to the indicative allocation provided by the British Government, some €1.6 billion would be earmarked for strengthening research, technological development and innovation. We estimate that considering all sources, the UK will lose more than €1.5 billion per year in direct EU funds for education and research.

The ESIF amount allocated to strengthening research, technological development and innovation for the period between 2014 and 2020 amounts to €1.6 billion, thus a yearly average of €226 million over the 7-year period.

The same report also claims that EU research funding creates more than 19,000 jobs and adds almost £2 billion to the UK economy, most of which is actually in industries outside the university sector.

One may also argue that Brexit will negatively impact other sources of funds (i.e. not from EU bodies), such as EU-based industry, public corporations and charities. A report prepared by Viewforth Consulting for Universities UK estimated these latter sources to provide 13% of the EU-wide total funding to UK universities.

Finally, it is worth considering that when the UK stops contributing to the EU budget, it will repatriate funds. The question is to what extent they will be reallocated to tertiary education and research to cover for the loss of EU funds.

We take the average over 2010-2015 in order even out differences between years. In 2015 the total contribution was exceptionally high, at over €18 billion (€10.7 billion in net contributions).

The UK’s total annual contribution to the EU budget is on average €13.5 billion, while the net annual contribution amounts to €6.6 billion. The amount of €13.5 billion represents the maximum that the UK can repatriate after it has negotiated how to meet future obligations with the EU. As shown above, €1.5 billion (or 11.3% of its total average annual contribution) comes back to the UK in the form of direct EU funds for education and research each year.

Maintaining the status quo in terms of expenditure in tertiary education and research in the UK will require using at least 11.3% of the amount freed as a result of leaving the EU.

Spending in R&D and tertiary education represents only 2.3% of the total 2015-16 UK budget. This shows that UK benefits from EU funds have been heavily concentrated in that sector. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that the British academic and scientific community fears losing that heavy benefit.

However, in an almost €900 billion annual budget, maintaining that extra €1.5 billion for R&D and education would mean an increase in budget allocated to the sector from 2.3% to 2.5%.

Conclusions

The effect of Brexit on EU students and staff residing in the UK will depend on conditions that the government puts in place. However, the sector itself already perceives this event as a significant distortion in their human capital and international reach.

On the funding side, the losses to the sector do not appear irrevocable. It naturally depends on negotiations between the two parties on the UK contribution to the budget.

There are however funding benefits that may not come directly from EU institutions that might cease. This will have an effect on universities and the way they contribute to the economy. This may explain why the majority of the sector’s representatives expressed major concerns about mobility, international cooperation and availability of funding in the long term.