The financial side of the productivity slowdown

Scholars have devoted much research to the “productivity puzzle” that has emerged after the crisis, and some are investigating the role of financial f

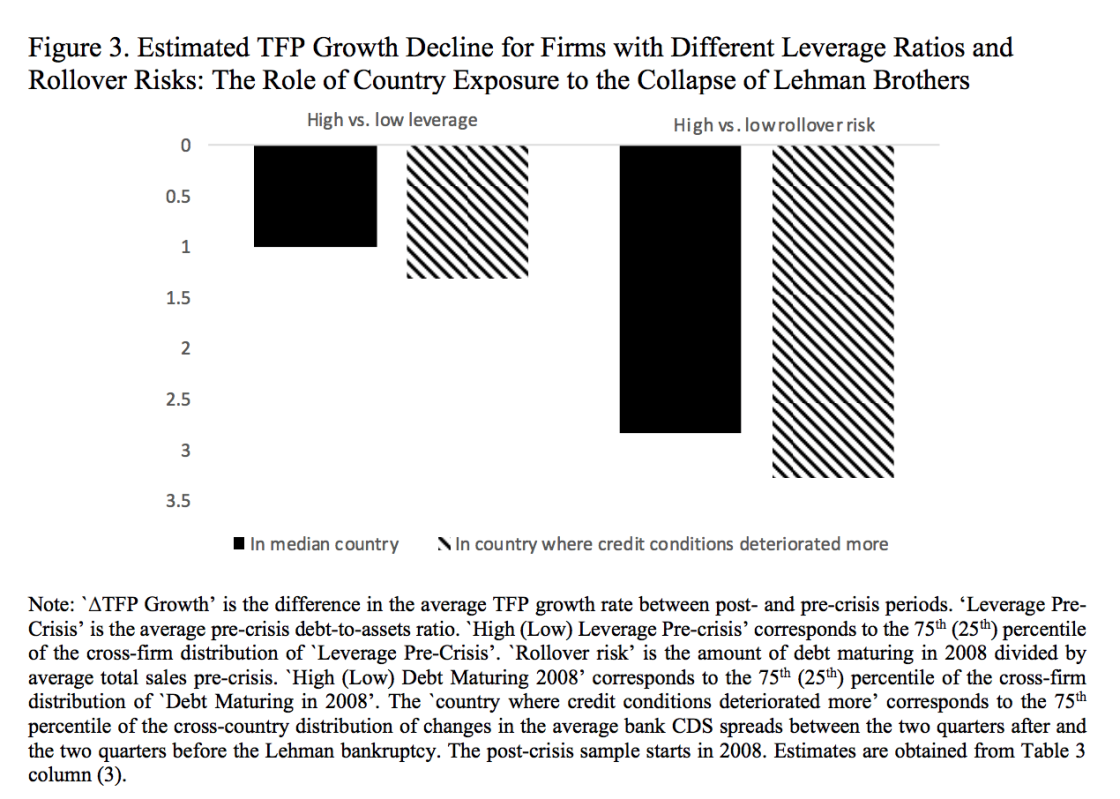

Romain Duval, Gee Hee Hong, and Yannick Timmer study the role of financial frictions in explaining the sharp and persistent productivity growth slowdown in advanced economies after the 2008 global financial crisis. Exploiting quasi-experimental variation in firm-level exposure to the crisis, they find that the combination of pre-existing firm-level financial fragilities and tightening credit conditions made an important contribution to the post-crisis productivity slowdown.

Specifically: (i) firms that entered the crisis with weaker balance sheets experienced decline in total-factor productivity growth, relative to their less vulnerable counterparts after the crisis; (ii) this decline was larger for firms located in countries where credit conditions tightened more; (iii) financially fragile firms cut back on intangible capital investment compared to more resilient firms, which is one plausible way through which financial frictions undermined productivity. All of these effects are highly persistent and quantitatively large – possibly accounting on average for about a third of the post-crisis slowdown in within-firm total-factor productivity growth.

Source: Duval et. al.

Isabelle Roland, Tim Besley and John Van Reenen develop and apply a theoretical framework to quantitatively assess the magnitude of financial frictions and their impact on aggregate productivity. The approach highlights a firm’s default probability as a sufficient statistic for credit frictions. The theoretical framework also suggests an aggregate measure of credit market inefficiency which can be applied to UK administrative panel data to explain how far the dramatic productivity slowdown in the wake of the crisis is due to credit market frictions. The paper finds that credit frictions cause a loss of 7-9% of GDP on average per year for the period 2004-12. These frictions increased during the crisis and lingered thereafter, accounting for between one-quarter and one-third of the productivity fall between 2008-2009 and for the gap between actual and trend productivity by the end of 2012.

Jagjit S. Chadha, Amit Kara and Paul Labonne look at the financial foundations of the productivity puzzle in the UK. They explore the role of overall and sectoral productivity in explaining the fall in labour productivity, but also question the extent to which productivity in the service sector may be measured with error. They outline the links between a constrained financial sector and a fall in overall productivity – in which intangible capital seems to play an important role – and illustrate how a financial sector providing intermediate services may act to amplify the business cycle impetus from a total-factor productivity shock within the context of a calibrated model.

In an older paper, Alina Barnett, Ben Broadbent, Adrian Chiu, Jeremy Franklin and Helen Miller explore whether impairment to capital reallocation has been contributing to weakness in UK productivity. Efficient allocation requires that capital moves to firms and sectors where rates of return are relatively high; but the change in capital levels across sectors has been particularly low, suggesting there has been an unusually slow process of capital reallocation since 2008 compared to previous UK recessions and banking crises. They show that increased price dispersion can be a consequence of frictions in efficient capital allocation and that the size of this dispersion can usefully inform us about the size of the associated output and productivity loss. Using firm level data, they find that the relationship between rates of return and subsequent capital movements has changed since the financial crisis, and impaired capital reallocation across the UK economy is likely to have been one factor contributing to the weakness in productivity growth.

Sara Calligaris, Massimo Del Gatto, Fadi Hassan, Gianmarco Ottaviano and Fabiano Schivardi argue that a crucial challenge in understanding what lies behind the “productivity puzzle” is the still-short time span for which data can be analysed. An exception is Italy, where productivity growth started to stagnate 25 years ago. Italy therefore offers an interesting case to investigate in search of broader lessons that may hold beyond local specific cities. Calligaris et al. find that resource misallocation has played a sizeable role in slowing down Italian productivity growth, to the extent that if misallocation had remained at its 1995 level, Italy's aggregate productivity in 2013 would have been 18% higher than the actual level. Misallocation has mainly risen within sectors rather than between them, increasing more in sectors where the world’s technological frontier has expanded faster. The broader message is that an important part of the explanation of the productivity puzzle may lie in the rising difficulty of reallocating resources between firms in sectors where technology is changing faster, rather than reallocating between sectors with different speeds of technological change.

Francesco Manaresi and Nicola Pierri also look at Italy. Exploiting a matched firm-bank database, covering all credit relationships of Italian corporations over more than a decade, they measure idiosyncratic supply-side shocks to firm credit availability and use it to estimate a production model augmented with financial frictions. They show that an expansion of credit supply leads firms to increase both their inputs and their value added and revenues for a given level of inputs. These estimates imply that a credit crunch will be followed by a productivity slowdown, as experienced by most OECD countries after the Great Recession. Quantitatively, the credit contraction between 2007 and 2009 can account for about a quarter of the observed decline in Italian total factor productivity growth.