Trump could give new impetus to EU-China relations

It is too early to say what the Trump administration’s trade policy will look like – but a total cut-off from Asian partners is unlikely. It would har

Donald Trump’s presidency threatens isolationism and could cause the United States to turn away from Asia. Trump’s statements so far, from his dislike of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) to his threat to impose massive import tariffs on Chinese goods, seem to indicate that he wants to undo Obama’s pivot towards Asia and the current “cordial” US relationship with China. However, this is easier said than done. A US disengagement from trade with Asia would help, rather than harm, China, while a more aggressive approach to the bilateral relationship with China would risk undermining US interests.

The irony of Trump’s plan to dismantle TPP is that it is based on the belief that China would enter TPP through the back door at a later date and hurt US interests. However, China is probably relieved at the likely demise of TPP, a trade agreement that would hamper China’s trade relationships with its most natural trading partners in Asia. Not only that, China would be able to strike back with its own regional trade arrangements with Asian partners. China has already moved in this direction by launching the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) initiative with all key Asia-Pacific trading partners: Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India and the Association of Southeastern Asian Nations (ASEAN). These countries account for as much as one quarter of US exports. If the US reneges on TPP but the RCEP proceeds nevertheless, then US exporters will be put at a serious disadvantage. In addition, the US would miss the opportunity to promote its rules and values in Asia, such as strict labour, environmental and intellectual property protection standards. Such an institutional deficit will leave US firms less protected in Asian markets than they would be with a successful implementation of TPP.

Meanwhile, a unilateral increase in US tariffs on Chinese goods would disrupt the global production chain. Although China seems to be more vulnerable than the US because China imports less from the US than the US from China, both countries are now heavily integrated into the supply chain and any shock from either side would be reciprocally painful. With the potential further integration of Asia’s economies under RCEP, one of Trump’s key messages during his campaign – the repatriation to the US of manufacturing jobs –is not likely to happen because jobs might actually stay in a more regionally integrated and increasingly consumption-driven Asia. Even worse for the US would be if China were to actively retaliate. This could take many forms given the still relatively large stock of US FDI in China and the interests of US companies that aim to tap into China’s huge consumer market.

More generally, given Asia’s size in terms of both GDP and population, it is hard to believe that the US would just step back and watch China take its place in Asia. This is no longer as unlikely as Trump might have thought when making such statements. The production and trade structures of China and the ASEAN bloc are increasingly complementary: China mainly imports oil, gas and other raw materials from the ASEAN countries, whereas they import electronics and textiles from China. There is also a growing production chain linking China and ASEAN countries in which US companies are not necessarily involved. The ASEAN bloc is now China’s third largest trading partner, surpassing the European Union. As such, Asia’s further integration through trade agreements is in the interests of all partners.

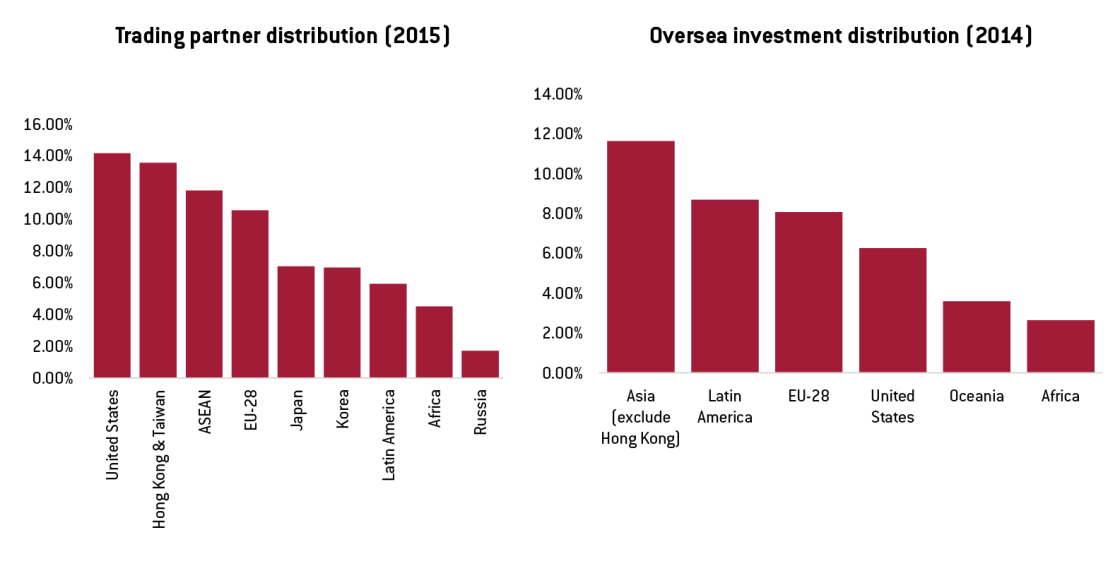

Figure 1: geographical distribution of China’s trade and investment

Sources: OECD Bilateral Trade Dataset (left figure); Ministry of Commerce, People's Republic of China (right figure).

However, China would not be completely satisfied with the idea of dominating Asia at the cost of losing the US market. A more practical possibility would be for the US – even under Trump – to cooperate with China in regional leadership among East Asian countries. Still, if Trump does keep his promises (no TPP, and barriers against China and perhaps others), China could cement its position in Asia and look beyond Asia to make up for the loss – namely, to Europe.

So, the most likely scenario is that many elements of the status quo hold: the Trump administration does not conclude TTP or TTIP successfully, but also does not impose protectionist measures on China because of the rebound effect on the US. Nevertheless, even in such a scenario where the US does not advance on regional trade agreements, China would have a first-mover advantage to China. Indeed, China’s rapid reactions to US hesitation over TPP during the last years of Obama’s administration sends a clear signal that China is unlikely to compromise with the US under a trade-adverse Trump. To our mind, Europe could be the next stop for China. This would be all the more logical given the hefty investment that China has planned –and started to carry out – for a much better connectivity with Europe under the Belt and Road Initiative.

As for the EU, closer economic relations with China might be the only call left in the absence of TTIP. The issue is more urgent against the backdrop of the potential RCEP agreement, whose members would account for about 30 percent of the EU’s external trade. If the EU cannot proceed with a favourable trade agreement with the region, its firms would also face trade diversion and enjoy less market access compared with other countries in the region such as China. In fact, the EU launched a plan to negotiate with the ASEAN countries in 2007 but the talks have moved to specific bilateral negotiations and progressed very slowly. Until now, out of the 10 ASEAN members the EU has only concluded free trade agreements with Singapore and Vietnam. Neither agreement has yet come into force. At the current juncture, with Asia-Pacific countries moving towards trade and investment integration, it is the time for the EU to speed up and rethink its strategy. The aim should be to reach a regional agreement with Asia-Pacific countries in which China plays an important role.

In any event, for Europe to move away from its long – although increasingly fruitless – transatlantic alliance towards China, it is vital to build real trust. This is even more important than railway connections. However, trust is currently at a low level, after the recent antidumping calls by the European Commission and China’s lack of reform to sectors over capacity. However, an inward looking, erratic and/or aggressive Trump administration might be the catalyst for a rapid increase in trust between the EU and China. In any case, the chances are that EU-China trade relations will improve under Trump.