Trade deficits and jobs at the ZLB

What’s at stake: In the populist narrative against globalization, trade deficits are seen as costing jobs. While this mercantilist view of the world i

Imbalanced trade in normal times

Neil Irwin writes that Donald Trump believes that a half-trillion-dollar trade deficit with the rest of the world makes the United States a loser and countries with trade surpluses like China and Mexico winners. Jared Bernstein writes that as long as there’s been trade, there’s been imbalanced trade, as countries invariably produce more than they consume, i.e., they’re run a trade surplus, while others, like us, will do the opposite. To somehow insist on balanced trade for all would be a huge policy mistake, one that would preclude billions of people from the reaping the benefits of trade, both as consumers and producers.

Neil Irwin writes that it’s true that the United States has a $58 billion trade deficit with Mexico, for example. But it’s not as if Americans were just flinging money across the Rio Grande out of charity. Americans get a lot of good stuff for that: avocados, for example, and Cancún vacations.

Source: EPI blog

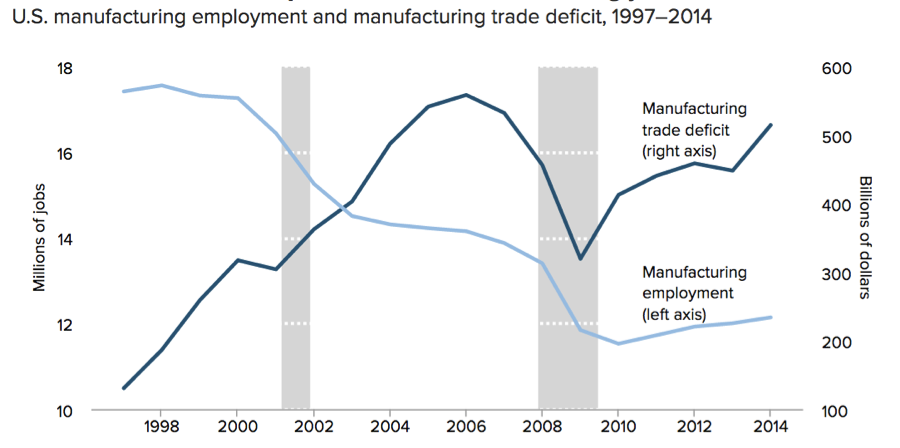

Robert Scott writes that while growing exports tend to support domestic employment, growing imports costs jobs and reduces domestic output. Thus, the size and growth of trade deficits is strongly correlated with trade-related job loss. Neil Irwin writes that it is true that a trade deficit subtracts from a country’s gross domestic product. So when a country is selling less stuff abroad than it buys from abroad, the country is making less stuff, and as a result there are fewer jobs. But when a country runs a trade deficit there is a countervailing force: capital inflows. Money flowing into a country is usually considered a good thing. It makes borrowing money cheaper, drives up stock prices and can mean more investment in new businesses. So does a trade deficit mean fewer jobs? It depends on which force is more economically powerful: fewer jobs creating exports or investment dollars flowing into the country.

Imbalanced trade at the ZLB

Paul Krugman writes that in normal times, the counterpart of a trade deficit is capital inflows, which reduce interest rates, and there’s no reason to believe that trade deficits reduce employment on net, even if they do redistribute it. But we are still living in a world awash with excess savings and inadequate demand, where interest rates can’t fall (or at any rate not much) because they’re already near zero. In that kind of world it’s true both that trade deficits do indeed cost jobs and that there are basically no benefits to capital inflows — we already have more desired savings than we are managing to invest.

Ricardo Caballero, Emmanuel Farhi, and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas write that at the ZLB, surplus countries push world output down, exerting a negative externality on the world economy. The global asset market is in disequilibrium: there is a global safe asset shortage, which cannot be resolved by lower world interest rates. It is instead dissipated by a world recession, which is propagated by global imbalances. Jared Bernstein writes that trade deficits are not bad in a “scorecard” sense, but when they persist because they are part of a strategy of mercantilist countries to over-save, under-consume, and under-invest, big problems evolve in lots of other places. Paul Krugman writes that if secular stagnation theorists are right — mercantilism makes a fair bit of sense.

Jared Bernstein writes that the happy version of capital inflows is that they put downward pressure on our interest rates, and we build all kinds of productive stuff that wasn’t being built at the higher rates that prevailed before our trade deficit got larger. The sad, and I fear more realistic version (and Bernanke got this right too in his 2005 paper that introduced the “savings glut” concept), is our rates are already crazy low and thus these flows lead to overinvestment, in dot.com junk, fiber optics, houses, oil rigs, and whatever else looks like the next big thing (the flows also push up the value of the dollar, which worsens the trade deficit). Dean Baker writes that insofar as foreigners invest their surplus dollars in U.S. assets not directly linked to employment (which will generally be the case) a trade deficit will be associated with higher unemployment, unless the economy has some other force generating employment to offset it.

The populist narrative on trade

Brad DeLong writes that the populist narrative goes like this: American middle – and working-class wages have stagnated because Wall Street pressed companies to outsource the valuable jobs that made up America’s manufacturing base, first to low-wage Mexicans and then to the Chinese. Moreover, this was a bipartisan effort, with both parties unified behind financial deregulation and trade deals that undermined the US economy. First, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) led to the export of high-quality manufacturing jobs to Mexico. Then the US established permanent normal trade relations with China and refused to brand its government a currency manipulator.

Brad DeLong writes it is not globalization, poor negotiation tactics, low-wage Mexicans workers, or the overly clever Chinese that bear responsibility for what is ailing America. The responsibility lies instead with politicians peddling ideology over practicality and failing to implement policies that manage globalization’s effects.