The trade-backlash explanation of Trump & Sanders

What’s at stake: The success of presidential candidates Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders has had bloggers wondered whether the backlash against globali

A working-class revolt against globalization

Jordan Weissmann writes that the near-simultaneous rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders has often been described as a working-class revolt against globalization and free trade—a bipartisan protest by blue-collar voters who are angry after watching factory after factory close thanks to foreign competition. Eduardo Porter writes that voters’ anger and frustration may not propel either candidate to the presidency. But it is already having a big impact on America’s future, shaking a once-solid consensus that freer trade is, necessarily, a good thing.

Paul Krugman writes that it’s true that much of the elite defense of globalization is basically dishonest: false claims of inevitability, scare tactics vastly exaggerated claims for the benefits of trade liberalization and the costs of protection, hand-waving away the large distributional effects that are what standard models actually predict. The elite case for ever-freer trade is largely a scam, which voters probably sense even if they don’t know exactly what form it’s taking.

Jordan Weissmann writes that researchers have found that Americans who live in parts of the country where industry has been hit hardest by foreign imports tend to vote against incumbent presidents. After two decades of free-trade consensus from both parties, Sanders, who dares describe himself as a democratic socialist, and Trump, who is Donald Trump, are campaigning as the ultimate anti-incumbents.

Explaining Michigan

Paul Krugman writes that a widespread guess for the Sanders win in Michigan is that his attacks on trade agreements resonated with a broader audience than his attacks on Wall Street and this message was especially powerful in the former auto superpower. Meanwhile, Donald Trump, while directing most of his fire against immigrants, has also been bashing the supposedly unfair trading practices of China and other nations.

Eduardo Porter writes that in a recent study, three economists — David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson — argue that local economies do not quickly recover from trade shocks. In theory, a developed industrial country like the United States adjusts to import competition by moving workers into more advanced industries that can successfully compete in global markets. The authors examined the experience of American workers after China erupted onto world markets some two decades ago. The presumed adjustment, they concluded, never happened. Or at least hasn’t happened yet. Wages remain low and unemployment high in the most affected local job markets. Nationally, there is no sign of offsetting job gains elsewhere in the economy.

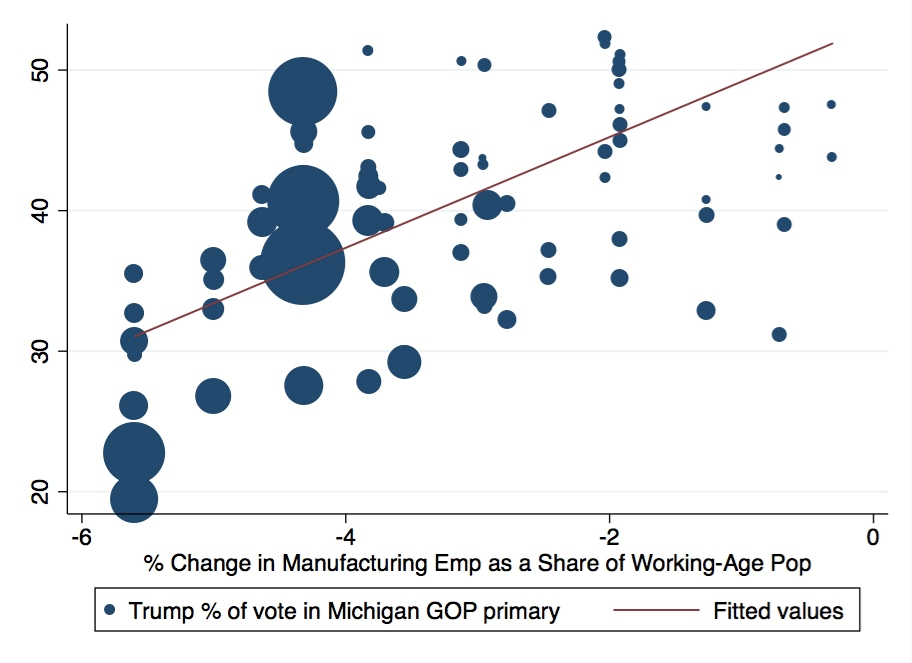

Evan Soltas writes that it's certainly plausible that Trump's and Sanders' strong performances in the Michigan primary are manifestations of a protectionist backlash. Using David Dorn's data on local declines in manufacturing and vote data from the Michigan Bureau of Elections, Soltas finds that the protectionist-backlash explanation of Trump and Sanders does not seem to hold up:

- Trump performed most strongly in areas where manufacturing's decline has been least important. Where manufacturing's decline was most intense, Trump received about 30 percent of the Republican vote, and where it was lightest, he received about 50 percent of the Republican vote.

- Sanders' county-level vote share in the Democratic primary is not significantly correlated with that county's change in manufacturing employment. No matter how intense the local decline in manufacturing, Sanders won about half the Democratic vote.

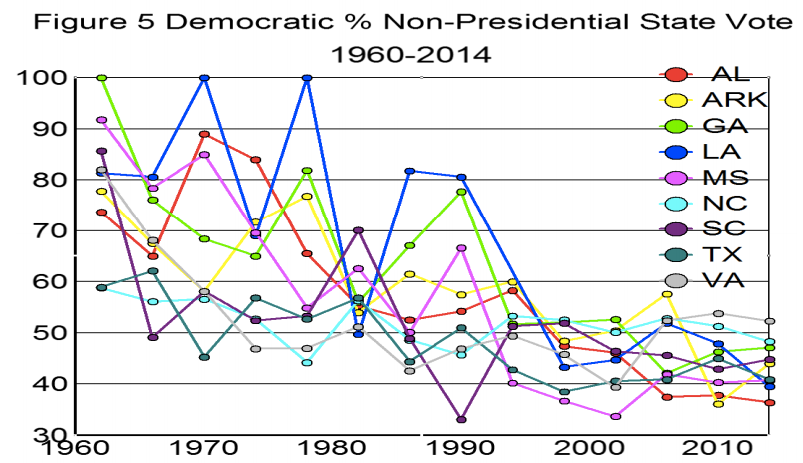

Manufacturing dis-employment and southern swing to the Republican Party

Gavin Wright writes that in contrast to popular belief the South only experienced a regime change in regional politics in 1994. In that year the Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives for the first time since the 1950s. The relatively sudden shift in partisan balance is often attributed to the redistricting decisions of the early 1990s. But the decline applies for states, whose boundaries did not change.

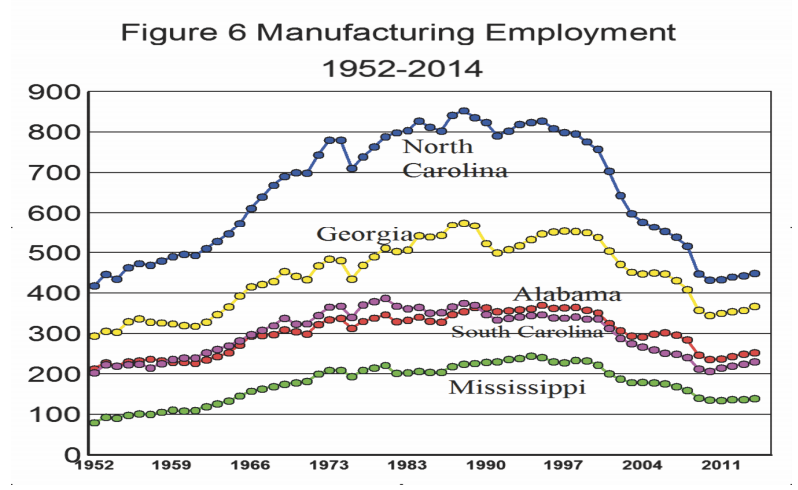

Gavin Wright writes that much of the South experienced wrenching economic dislocation at precisely this time, as the manufacturing industries that had formed the core of the regional economy began their historic descent in response to import competition. The leading contributors were textiles and apparel, industries in which employment fell far more rapidly than U.S. manufacturing generally. There is ample testimony that deindustrialization and economic stagnation have been the dominant facts of life for white southerners in recent decades. The travel writer Paul Theroux spent three years traveling in the South and reported: ``if there is one experience of the Deep South that stayed with me it was the sight of shutdown factories and towns with their hearts torn out of them, and few jobs. There are outsourcing stories all over America, but the effects are stark in the Deep South…I found towns in South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas that looked like towns in Zimbabwe, just as overlooked and beleaguered.”