Is the ECB collateral framework compromising the safe-asset status of euro-area sovereign bonds?

Central banks’ collateral frameworks play an important role in defining what is considered as a safe asset. However, the ECB’s framework is unsatisfac

While sound public finances are a prerequisite for sovereign bonds to be considered safe, the central bank plays a crucial role in defining asset safety given its position as a protector of the currency’s value and as a potential backstop in a liquidity crisis (as argued in a previous blog post). However, in practice, the central bank also matters because of what assets it accepts as collateral in its refinancing operations and how it values them.

Haircuts applied in these monetary operations are utterly relevant in forging financial markets’ perceptions of the safety of a debt security, as haircuts’ levels determine whether financial institutions will be able to exchange these assets easily and almost at par against the ultimate safe asset: central bank reserves.

Currently, eligibility and haircuts applied by the ECB in its refinancing operations depend on four elements: 1) the type of asset, 2) the type of issuer, 3) the residual maturity and 4) the rating of the issuer of the asset.

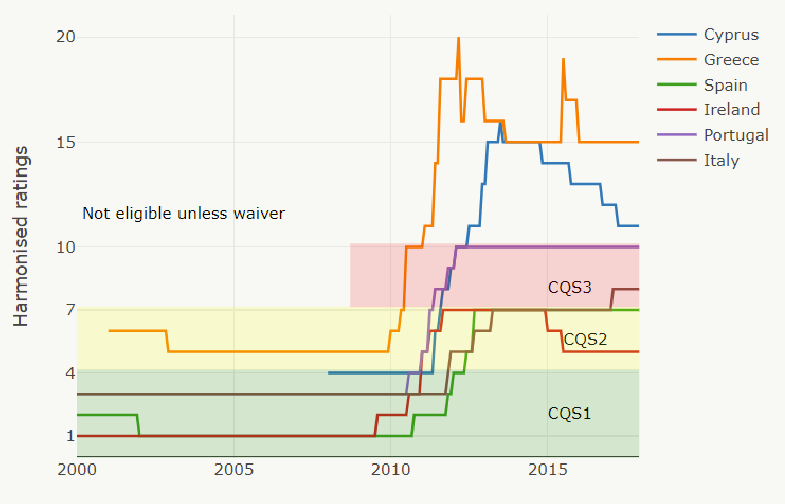

This means that the current approach to valuing haircuts in refinancing operations relies heavily on the ratings made by private credit rating agencies. In fact, to determine its own rating of a particular sovereign bond, the ECB takes the best rating out of four accepted credit rating agencies (Moody’s, Fitch, S&P and DBRS) and maps it to the three “credit quality steps” of the Eurosystem harmonised rating scale (Figure 1).

How have haircuts on sovereign bonds evolved since the creation of the monetary union, and in particular during the crisis? To our knowledge, the resulting ECB ratings (and thus the haircuts applied) are not directly available, but it is easy to replicate them using the long-term ratings of the four credit rating agencies for each euro-area sovereign.

Taking into account the various changes in the ECB’s collateral framework that have taken place since 2008 (see details for instance in Wolff, 2014), this allows us to determine the eligibility and haircuts applied to euro-area countries debt securities.

Figure 1. Sovereign ratings and ECB credit quality steps

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg and the ECB.

Note: The ratings on the vertical axis are computed as the first best rule between the four external credit ratings translated into numerical grades from 1 to 20. Ratings from 1 to 4 correspond to the ECB credit quality step (CQS) 1, ratings from 5 to 7 to CQS 2 and ratings from 8 to 10 to CSQ 3 (which did not exist before October 2008).

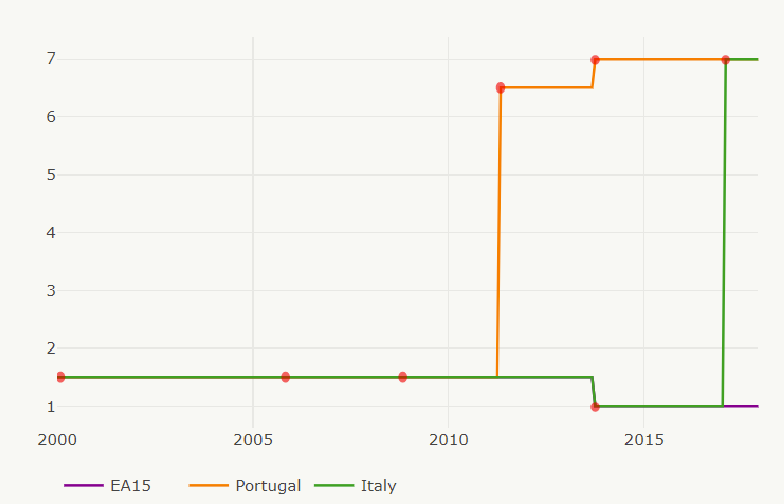

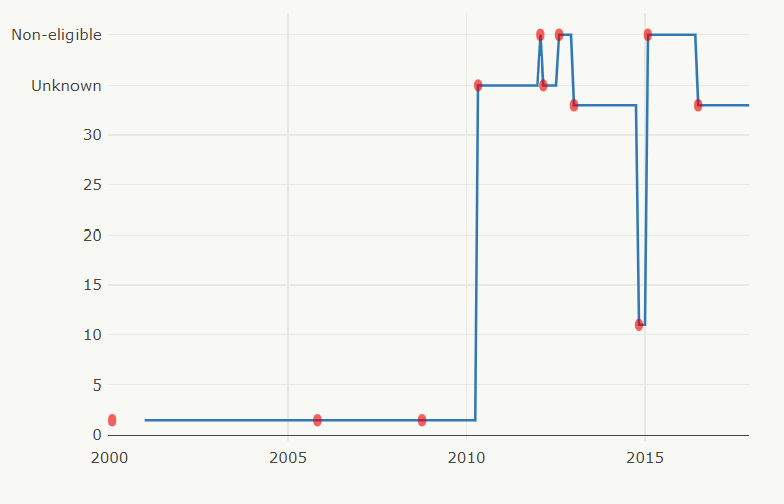

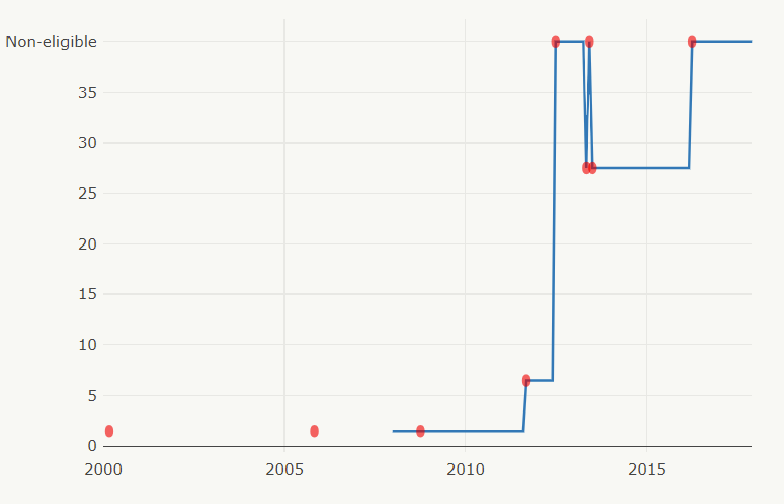

As an example, Figure 2 shows the evolution of haircuts applied to one-year fixed coupon government bonds of all euro-area countries (changes in haircuts of bonds of other maturity would be very similar, even though levels would differ).

Figure 2. ECB haircuts for one-year government bonds with fixed coupons (in %)

Panel A. Euro-area 15, Italy and Portugal

Panel B. Greece

Panel C. Cyprus

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg and the ECB.

Note: The events leading to changes in haircuts valuation are signalled by red dots (a description is available by hovering over them). EA-15 includes all euro-area countries other than Portugal, Italy, Greece and Cyprus, each from the respective date of accession. In 2010, the ECB announced the continued eligibility of Greek debt despite its downgrade below BBB- until February 2012 but did not disclose the haircuts applied. From March to July 2012, it communicated the acceptance of debt instruments issued by the government of Greece subject to a buy-back scheme, but again did not disclose the haircuts applied. That is why haircuts are labelled as “unknown” in the chart.

In our view, Figure 2 highlights the two main issues of the current framework:

- First, relying on pro-cyclical ratings from external credit rating agencies (visible in Figure 1) can lead to abrupt swings in haircuts. Before the crisis, this approach resulted in applying the same haircut to every euro-area sovereign bond with the same maturity, signalling to markets that all bonds were of the same quality. During the crisis – and despite the ECB’s adjustments to its collateral framework – the quick downgrades of some sovereigns led to significant changes in applied haircuts.

- Second, differences in haircuts between the different ECB credit quality steps are not gradual enough to adequately reflect the different increases in risk levels. For instance, the current haircut for a sovereign bond with a residual maturity of one-year rated A- is equal to 1%, while it is 7% for a similar bond rated BBB+, just one grade below (in the S&P and Fitch scale). This is what happened to Italian bonds in February 2017.

It is important for the ECB to properly value haircuts to protect its balance sheet and to avoid bad incentives for governments as well as for financial institutions holding these assets. However, the current way to value haircuts is inadequate as it leads to large changes in haircuts that could influence, among other things, the way financial institutions perceive the safety of these assets.

We make some suggestions to solve these issues:

- First, if using ratings from credit rating agencies in central banks’ collateral framework is not fully satisfactory (as also suggested by the Financial Stability Board in 2010), what else can be done? A first possibility would be for the ECB to use its own criteria to value haircuts, as the Bank of England (BoE) and many other central banks around the world do. However, given the multi-country nature of the euro area and the potential distributional consequences that significant ECB losses could induce between countries – through a reduction of future seigniorage profits, or possibly through higher inflation – the ECB is in a much more complex situation than a central bank like the BoE, which only has to deal with one treasury. In this context, to avoid the risk of the ECB appearing politicised (as in February 2015 when it decided to withdraw the waiver that was making Greek bonds eligible as collateral despite their low rating), it might be preferable for the ECB to still rely on an external risk assessment. In that case, a possible alternative to private ratings could be to use a debt sustainability analysis that would be done, for instance, by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). This situation would not be perfect either, as it could lead to heated political debates between countries at the ESM. But, in our view, it would still be better than delegating these decisions to private rating agencies which cannot be held accountable for their potential mistakes and for the pro-cyclicality of their ratings. For lack of a better institution (e.g. a euro-area Treasury or any other form of executive body) and despite its flaws in terms of governance, the ESM board (formed by Eurogroup finance ministers) is currently the only political body able to take this type of decision at the euro-area level. Alternatively, haircuts could also be based on past performances of countries regarding their respect of European fiscal rules. These would first need to be improved to avoid mistaken recommendations.

- Second, the ECB’s rating scale and the corresponding haircut valuation should be made more gradual. There are currently only three steps in the ECB scale (and the first two share the same haircut valuation), while there are 10 different grades from rating agencies that are eligible as collateral. Having a more granular scale would make haircut changes smoother and provide better incentives to governments and financial participants.

Despite their fundamental differences, the comparison between the frameworks of the ECB and the BoE is enlightening. As the BoE explains, “haircuts are set so as to be broadly stable in the light of changing market conditions” in order to 1) provide the central bank “with adequate protection of its balance sheet”, but also 2) provide “greater certainty to counterparties”. Indeed, relying on its own criteria and not on external ratings allowed the BoE to keep haircuts applied to eligible sovereign bonds – including Italian and Portuguese bonds – stable in recent years, while the ECB mechanistically revised its haircuts when ratings were downgraded.

The institutional setup of the euro area is, in its essence, much more challenging than the relationship between the BoE and the UK government. However, it does not mean that the ECB framework cannot evolve to balance these two essential objectives better in order to continue protecting its balance sheet without putting at risk the safe status of sovereign bonds of the euro area.

The authors would like to thank Francesco Chiacchio for his help with the data visualisation.