Compliance principles for the Digital Markets Act

This paper proposes an original set of five compliance principles derived from the DMA list of obligations.

Executive summary

Under the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), six ‘gatekeepers’ (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft) have been designated in relation to 22 core platform services (CPS). The gatekeepers have until 6 March 2024 to propose to the European Commission how they will comply with their DMA obligations.

The DMA gives flexibility to gatekeepers to achieve compliance by providing some guidance what can constitute compliance and non-compliance with the obligations. However, it does not provide compliance principles. These offer a standard of compliance-by-design, while offering flexibility to each gatekeeper to develop specific solutions tailored to each obligation and CPS. Compliance principles would also be easily observable elements helping to inform the Commission – the DMA’s enforcer – aboutcompliance.

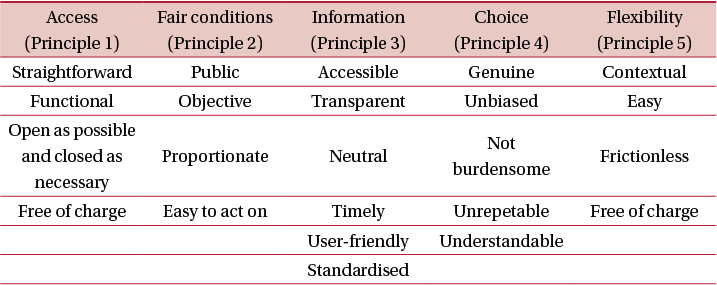

We propose fiveDMA compliance principles for gatekeepers to follow. These have been derived from the list of DMA obligations. The principles relate to access, fair conditions, information, choice and flexibility. Each principle would be accompanied by a second level of sub-principles based on the economics literature and case law.

We recommend that gatekeepers implement the principles and that the Commission monitors whether gatekeepers follow the compliance principles. Gatekeepers, in their annual DMA compliance reports, should provide the Commission with methodologies, tests and other relevant documents as evidence of compliance in practice. Commission monitoring should include regular engagement with gatekeepers, third parties and consumers, before and after the implementation of the compliance solutions.

1 Introduction

Europe’s landmark Digital Markets Act (DMA) is entering its compliance phase, in which the law’s obligations for large online platforms acting as gatekeepers, or hard-to-avoid digital service gateways, start to kick in. In relation to specific core platform services (CPSs), gatekeepers, which include Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft, have until 6 March 2024 to propose how they will comply with the DMA to the European Commission, which is the sole enforcer

1

ByteDance in relation to TikTok and Meta (in relation to two CPSs: Meta Marketplace and Messenger) are appealing against the gatekeeper designations, but the appeals do not have suspensive effect and the companies must still comply with the DMA list of obligations by 6 March 2024. See Supantha Mukherjee and Foo Yun Chee,

.

The gatekeepers must explain how they will achieve effectively the DMA’s objectives in ensuring contestable and fair digital markets (Articles 1 and 8 DMA). Gatekeepers must allow business users to challenge their products and services by ensuring market entry and by offering balanced terms and conditions (Recital 32 and 33 DMA). This will give European consumers more options to choosebetween products and services offered by both gatekeepers and business users. The Commission must monitor compliance with the obligations (Articles 5, 6 and 7 DMA), and in case of non-compliance, will enforce the rules by imposing penalties of up to 20 percent of global turnover (Article 30 DMA) and behavioural and structural remedies, such as break up of gatekeepers (Article 18 DMA).

There are already several studies on DMA compliance. They focus on indicators to help in monitoring the effectiveness of the DMA (Feasey and De Streel, 2023; Crémer et al, 2022). They propose measures of how users engage with gatekeepers (output indicators, for example the percentage of apps from gatekeepers that have been uninstalled over a period by consumers) and of changes in market conditions (outcome indicators, for example the number of users using a service not provided by a gatekeeper during a relevant period). While relevant for policy, these are not actually indicators of compliance (Carugati, 2023a). Indeed, the DMA requires gatekeepers to make their best efforts to comply by empowering users with rights,but does not oblige gatekeepers to achieve an outcome (for example, that 50 percent of Apple iPhone users use a third-party app store in the next five years). Other studies have proposed compliance indicators that assess user empowerment by monitoring how gatekeepers engage with businesses and consumers – for example whether gatekeepers provide the ability to accept or decline consent easily (Carugati, 2023a).

Compliance principles would offer a compliance-by-design standard while offering flexibility to each gatekeeper to develop specific solutions

However, there have been so far no studies on compliance principles to follow whendesigning compliance solutions. Such principles would offer a compliance-by-design standard while offering flexibility to each gatekeeper to develop specific solutions tailored to each rule and CPS. Respecting such principles would also be easily observable, informing the Commission about compliance. In other words, compliance principles would be cost-effective for DMA implementation and monitoring.

This policy contribution fills this gap. It proposes an original set of fivecompliance principles derived from the DMA list of obligations. It then outlines how they can be implemented through a series of second-level principles derived from the DMA list of obligations and recitals, and from relevant caselaws and literature, and how they can be monitored by both gatekeepers and the Commission.

2 Defining compliance principles

2.1 Context

The DMA imposes positive and negative obligations (Articles 5, 6, and 7 DMA) on large online platforms designated as gatekeepers in relation to a CPS (Box 1). These obligations draw from past and current competition law cases dealt with bythe Commission and national competition authorities. For instance, the prohibitions on self-preferencing (or a gatekeeper giving its own services or product more favourable rankings; Article 6(5) DMA) and on combining data without consent (Article 5(2) DMA) draw from the 2017 European Google Shopping case

2

AT.39740 Google Search (Shopping), 27 September 2017. The case is still pending before the European Court of Justice after the Court backed the Commission’s finding in the first instance. C-48/22 P Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping) (pending).

and the 2019 German Facebook case

3

B6-22/16 Facebook, 6 February 2019.

, respectively.

However, the DMA differs from traditional competition law. It focuses on compliance through the imposition and prohibition of practices ex ante. By contrast, competition laws focus on enforcement by remedying ex post anticompetitive conducts that have negative effects on competition. Therefore, under the DMA, gatekeepers must ensure that their products and services are DMA-compliant by design from a legal and technical standpoint (Recital 65 DMA).

Box 1: Designation of gatekeepers

The DMA only applies to gatekeepers in relation to a core platform service. The latter include online search engines, online social networking services, video-sharing platform services, messaging services, operating systems, web browsers, virtual assistants, cloud computing services and online advertising services by a firm that provides one or more CPS (Article 2 DMA).

On 6 September 2023, the Commission published the first list of designated gatekeepers, which includes six gatekeepers in relation to 22 CPSs

4

See https://digital-markets-act-cases.ec.europa.eu/search.

:

Alphabet: Google Maps, Google Play, Google Shopping, YouTube, Google Ads, Google Search, Google Chrome and Google Android.

Amazon: Amazon Marketplace and Amazon Ads.

Apple: Apple App Store, Apple Safari and Apple iOS.

ByteDance: TikTok.

Meta: Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger, Meta Marketplace and Meta Ads.

Microsoft: LinkedIn and Windows PC OS.

In addition, the Commission opened five market investigations to assess whether Microsoft Bing, Microsoft Edge, Microsoft Advertising, Apple iMessage and Apple iPad OS are CPSs 5 For more details about the designation of gatekeepers, see Carugati (2023b). .

The DMA does not tell gatekeepers how to achieve effective compliance. Gatekeepers have the flexibility to implement necessary and proportionate compliance solutions. However, at the time of writing, gatekeepers are still drafting compliance solutions, and have not released publicly how they intend to comply with their DMA obligations. In this context, our recommended compliance principles are timely to guide the development of these compliance solutions. The proposed principles are also useful for monitoring compliance with the obligations, as the principles are derived from the obligations.

The fundamental issue is what constitutes compliance. The DMA provides some interpretative indications in the recitals (Recitals 36 to 64 DMA). It also indicates what constitutes non-compliance when gatekeepers circumvent the obligations by engaging in practices undermining effective compliance (Article 13 DMA). While this is helpful, it is not entirely informative about what constitutes compliance. Against this background, clear compliance principles can guide gatekeepers in designing compliance solutions based on and deduced from the obligations, recitals, case law and literature.

2.2 Methodology

We have derived a set of recommended compliance principles from the DMA obligations. The principles are intended tobe flexible, objective and neutral in terms ofthe means to achieve them, so that gatekeepers can adapt them to each rule and CPS. The five top-line principles would be implemented via observance of additional second-level principles (section 3. 1).

The principles will help gatekeepers adhere to the DMA’s positive and negative obligations, which are as follows:

- Control over data: The DMA prevents some data combination and usage (Articles 5(2) and 6(2) DMA). It also requires gatekeepers to grant access to certain data to businesses (Article 6(10) DMA) or rivals of online search engines (Article 6(11) DMA).

- Price-parity clauses: The DMA prohibits clauses that prevent businesses from offering better prices and conditions via third-party channels (Article 5(3) DMA).

- Unfair terms and conditions: The DMA prevents restrictions on access and use of certain services (Articles 5(4) and 5(5) DMA), or complaints to public authorities and courts (Article 5(6) DMA). It also imposes obligations to ensure reasonable conditions of access and termination of services (Articles 6(12) and 6(13) DMA).

- Anticompetitive tying and bundling: The DMA prohibits gatekeepers from making access to their CPSs conditional on the purchase (tying) of ancillary identification services, web browser engines or payment services (Article 5(7) DMA) or other gatekeepers’ CPSs (Article 5(8) DMA). It also prohibits undesired bundling of different services.

- Lack of transparency: The DMA imposes transparency in online advertising services (Articles 5(9), 5(10), and 6(8) DMA).

- Pre-installation and defaults: The DMA requires that users are given the ability to uninstall pre-installed services (Article 6(3) DMA).

- Lack of switching: The DMA requires gatekeepers to allow end-users to download software from the web or alternative application stores (Article 6(4) DMA). It also requires users to be able to switch from one software application to another (Article 6(6) DMA).

- Anticompetitive self-preferencing: The DMA prevents gatekeepers from promoting their own services over rivals in ranking, crawling and indexing (Article 6(5) DMA).

- Lack of effective interoperability: The DMA requires that third-party products and services should be able to work with the platform (Article 6(7) DMA) and that messaging service providers can communicate with one another (Article 7 DMA).

- Lack of effective data portability: Under the DMA, gatekeepers must allow data portability of personal and non-personal data continuously and in real-time (Article 6(9) DMA).

From these obligations, the following compliance principles can be derived:

- Access (Principle 1): Gatekeepers shall provide access to inputs, services and products. This relates to provisions on control over data (Articles 6(10) and 6(11) DMA), unfair terms and conditions (Articles 5(4) and 5(5) DMA), anticompetitive tying and bundling (Articles 5(7) DMA), lack of switching (Article 6(4) DMA), lack of effective interoperability (Articles 6(7) and 7 DMA), lack of transparency (Article 6(8) DMA) and lack of effective data portability (Article 6(9) DMA).

- Fair conditions (Principle 2): Gatekeepers shall propose non-discriminatory treatment. This relatesto provisions related to control over data (Article 6(2) DMA), price-parity clauses (Article 5(3) DMA), unfair terms and conditions (Articles 5(6), 6(12) and 6(13) DMA) and anticompetitive self-preferencing (Article 6(5) DMA).

- Information (Principle 3): Gatekeepers shall provide information that willallow users to make meaningful choices. This relates to provisions related to control over data (Articles 5(2) DMA), and lack of transparency (Articles 5(9) and 5(10) DMA)

- Choice (Principle 4): Gatekeepers shall enable options in the use of services. This relatesto provisions related to anticompetitive tying and bundling (Articles 5(7) and 5(8) DMA), pre-installation and defaults (Article 6(3) DMA) and lack of switching (Articles 6(4) DMA).

- Flexibility (Principle 5): Gatekeepers shall allow users to switch seamlessly between services. This relates to provisions related to lack of switching (Article 6(6) DMA).

However, these compliance principles have some limitations arising fromtheir flexibility. They offer a general framework for compliance but are not specific for each rule and CPS. Accordingly, the principles are non-exhaustive. Gatekeepers should read them alongside the DMA’s interpretive indications for each rule, to ensure compliance.

While the compliance principles offer a standard of compliance that each gatekeeper should follow, they also provide the Commission with a baseline for monitoring of compliance. They can guide gatekeepers and the Commission towards effective compliance by providing a list of clear-cut elements to implement and monitor. Compliance principles are thus cost-effective because they are easily implementable by gatekeepers and observable by third parties and the Commission, in line with the DMA obligations and recitals. In sum, the implementation or non-implementation of these principles can act as a flag to identify potential compliance or non-compliance with the obligations.

3 Components of the principles

3.1 Implementation

The implementation of each of the compliance principles will require adherence to a second level of principles, or underpinning principles. We have derived these from the DMA list of obligations and their recitals and relied on appropriate caselaw and literature (cited in each sub-section below). Table 1 summarises the principles and underpinning principles.

Table 1: Proposed DMA compliance principles and their components

3.1.1 Access (Principle 1)

The access principle aims to enable third parties to access the gatekeeper’s inputs, products and services. This will allow third parties to offer alternative products to those offered by gatekeepers. While access might have positive competitive effects by lowering entry barriers, it might also have negative effects by reducing the incentive for gatekeepers to innovate, especially in future data collection (Digital Competition Expert Panel, 2019).

Moreover, access poses privacy and security issues. For instance, when accessing or allowing access to personal data, gatekeepers must request the user’s consent in line with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), to protect user privacy. Security risksalso arise,if access to the operating system allows malicious actors to undermine the system. In this context, the DMA requires access with some necessary and proportionate limitations to protect incentives fordata collection, privacy and security.

At the same time, access is not entirely new. Several laws, such as the GDPR, already requiredata access in connection with the right of data portability (Article 20 GDPR), which allows users to move their data from one service to another. However, in practice, data portability can be complicated and might not work at all because of the lack of technical standards, which makes data reuse difficult or impossible (Digital Competition Expert Panel, 2019; Crémer et al, 2019). Against this backdrop, gatekeepers should respect the following underpinning principles when granting data access.

- Straightforward: Access to inputs, services and products should be easy with reasonable access conditions. The Dutch Apple App Store case (Box 2) shows that a gatekeeper can have the incentive to impose unreasonable conditions in orderto deter entry.

-

Functional: Access should enable reuse in a commonly used format and with the technical means that allow third parties direct access, such as via the provision of application programming interfaces (APIs).

- Open as possible and closed as necessary: Access should be open, except when privacy and security issues require necessary and proportionate restrictions, in line with the obligation to protect the integrity of the system with proportionate security and privacy measures.

- Free-of-charge: To promote entry, access should be free. When a charge isallowed, it should be proportionate to the service provided, the investment required, the value of the input or the cost of access 6 .

Box 2: The Dutch Apple App Store case

In December 2021, the Dutch competition authority, the Autoriteit Consument & Markt (ACM), ruled that Apple must allow third-party in-app payments for providers of dating apps in its Apple App Store in the Netherlands

7

See Autoriteit Consument & Markt press release of 24 December 2021, ‘ACM Obliges Apple to Adjust Unreasonable Conditions for its App Store’, https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/acm-obliges-apple-adjust-unreasonabl….

, similar to the DMA provision requesting alternative in-app payment systems (Article 5(7) DMA). Apple first proposed in February 2022 that dating app developers should create new applications of their apps to provide alternative in-app payments. However, the authority considered this condition unnecessary and unreasonable

8

See Autoriteit Consument & Markt press release of 14 February 2022, ‘Developing a New App is an Unnecessary and Unreasonable Condition that Apple Imposes on Dating-App Providers’, https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/acm-developing-new-app-unnecessary-a….

. In a final proposal, Apple dropped this requirement and proposed using third-party in-app payments in exchange for a 27 percent commission fee

9

See undated Apple notice, ‘Distributing Dating Apps in The Netherlands’, https://developer.apple.com/support/storekit-external-entitlement/.

. The Dutch competition authority accepted Apple’s change and considered it compliant

10

See Autoriteit Consument & Markt press release of 11 June 2022, ‘Apple Changes Unfair Conditions, Allows Alternative Payments Methods in Dating Apps’, https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/acm-apple-changes-unfair-conditions-….

.

3.1.2 Fair conditions (Principle 2)

The fair conditions principle aims to correct the imbalance of power between gatekeepers and their customers. Too much power on the gatekeeper side might lead to the imposition of unfair conditions, such as parity clauses

11

For example, several national competition authorities prohibit Booking.com from imposing parity clauses on its business customers, which prevent them from offering better prices to alternative platforms. See Decision n° 15-D-06 of the French competition authority, the Autorité de la concurrence, in 2015: Booking.com, 21 April 2015, https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/fr/decision/sur-les-pratiques-mi….

or discriminatory terms

12

For example, the French competition authority imposed in May 2023 interim measures against Meta to tackle unfair terms practices. See Decision 23-MC-01 Meta advertising, 4 May 2023, https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/en/decision/request-company-adlo….

. While the concept of fairness can be subjective, case law has identified instances of unfairness involving terms that are not transparent, objective, proportionate or easy to act on

13

Ibid. See also the French competition authority’s decision against Google on tackling unfair terms in the search advertising market. Decision n°19-D-26 Google advertising, 19 December 2019, https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/fr/decision/relative-des-pratiqu….

. Against this background, gatekeepers should define terms and conditions based on the following underpinning principles:

- Public: The conditions should be publicly available with transparent terms, clearly understandable and predictable, set out in plain and intelligible language.

- Objective: The conditions should be based on objective and justified criteria.

- Proportionate: The conditions should be justified and reasonable relative to the pursued objective or service provided.

- Easy to act on: The conditions should enable a simple and understandable action with minimalsteps, as illustrated by conditions on service termination (Box 3) 14 Gatekeepers should enable businesses to offer differentiated commercial conditions (Article 5(3) and Recital 39). Gatekeepers should enable businesses and consumers to raise concerns (Article 5(6) and Recital 42 DMA). Gatekeepers should not use certain business data (Article 6(2) and Recitals 46, 47 and 48 DMA). Gatekeepers should not engage in differentiated or preferential treatment in ranking, indexing and crawling, in order to favour their own products or services. The conditions for ranking should be fair and transparent (Article 6(5) and Recitals 51 and 52 DMA). Gatekeepers should publish and apply fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory general access conditions. The conditions should be proportionate to the service provided and the pursued objective, such as measures to fight illegal content (Article 6(12) and Recital 62 DMA). Gatekeepers should not make it unnecessarily difficult or complicated to unsubscribe. Unsubscribing should not be more complicated than subscribing. The conditions of termination of a contract should be proportionate and can be exercised without undue difficulty (Article 6(13) and Recital 63 DMA). .

Box 3: Conditions imposed on service termination

Firms often make it very easy to subscribe to a new service to ensure frictionless access. However, to retain customers, some firms make it difficult to unsubscribe and terminate a service. For instance, in the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) alleged in June 2023 that Amazon’s conditions of termination are not easily actionable. According to the ongoing complaint, Amazon allegedly makes it simple to subscribe to its service, Amazon Prime, but makes it difficult to unsubscribe by requiring multiple steps, in order to deter consumers from cancelling their subscriptions

15

Federal Trade Commission press release of 21 June 2023, ‘FTC Takes Action Against Amazon for Enrolling Consumers in Amazon Prime Without Consent and Sabotaging Their Attempts to Cancel’, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/06/ftc-takes-a….

. Amazon has denied the allegations

16

Mike Scarcella, ‘Amazon Defends Prime Program in Bid to Defeat FTC Lawsuit’, Reuters, 19 October 2023, https://www.reuters.com/legal/amazon-defends-prime-program-bid-defeat-f….

.

The DMA might consider this practice non-compliant,because it states explicitly that gatekeepers should not make it unnecessarily difficult or complicated for users to unsubscribe from a CPS (Recital 63 DMA). Difficult processes to terminate a servicemight also be considered as a circumvention if they subvert the user’s autonomy (Article 13(6) DMA).

3.1.3 Information (Principle 3)

Under the information principle, users should be informed about how they can exercise their DMA rights. While information is important for making meaningful decisions, studies have found that reading terms and conditions is time-consuming (McDonald and Cranor, 2008) and users often do not read terms and conditions, or do not fully understand them (OECD, 2018). Users sometimes have no choice but to accept them if they want to use or continue using the service (Carugati, 2023c)

17

For instance, in Germany, the German competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt, in February 2019 prohibited Facebook from combining user personal data from different sources without the user’s consent, like the DMA prohibition on combining data without consent. See Decision B6-22/16, ‘Facebook, Exploitative business terms pursuant to Section 19(1) GWB for inadequate data processing’, 15 February 2019, https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Entscheidung/EN/Fallberichte…. In Germany, Google also committed in October 2023 to not combine data without the user’s consent, following a German investigation under the DMA-like national competition law. See Decision B7-70/21, ‘Bundeskartellamt gives users of Google services better control over their data’, 5 October 2023, https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Entscheidung/EN/Entscheidung….

. Studies have also found that firms of all sizes frequently use manipulative or deceptive language and design elements to steer users towards choices that are in the firm’s best interest– practices known as dark patterns (Box 4). Against this background, the informationprinciple should be underpinned by the following principles:

- Accessible: The information should be understandable to the public and available in an appropriate document to avoid reading lengthy general terms and conditions in order to read the necessary part.

-

Transparent: The information should provide necessary and clearly understandable terms with their meanings and implications, to ensure that users understand fully the necessary elements to make a meaningful decision.

- Neutral: The information should be provided objectively with neutral language and design elements to avoid dark patterns.

-

Timely: The information should be provided when users need it to exercise their rights to ensure that they understand their decisions at the right time.

-

User-friendly: The information should be provided in a user-friendly way through pictograms or other graphical elements to ease comprehension, when possible and appropriate.

- Standardised: The information should use a standard to ease comparison and comprehension (eg same unit pricing, similar consent banner) 18 Gatekeepers should request the user’s consent for some data-processing activities with a user-friendly solution and in an explicit, clear and straightforward manner. Not consenting should not be more difficult than consenting, and withdrawing consent should be as easy as giving it. Gatekeepers should not design their online interfaces in a deceptive or manipulative way and cannot prompt users more than once a year (Article 5(2) and Recitals 36, 37, and 38 DMA). Gatekeepers should provide free-of-charge information about advertising prices on a daily basis, allowing comparison (Articles 5(9) and 5(10) and Recital 45 DMA). .

Box 4: Dark patterns

Dark patterns are manipulative or deceptive techniques used to steer customers in line withthe firm’s interests (OECD, 2022). Users might encounter dark patterns when engaging with an online choice architecture, such as a choice screen. Techniques can include different contrasts, fonts and colours, to steer the user’s choice (CMA, 2022;CMA and ICO, 2023). Dark patterns harm both consumers and competition. These misleading practices prevent users from making meaningful choices between providers, negatively impacting competition. The DMA explicitly prohibits dark patterns (Article 13 DMA).

3.1.4 Choice (Principle 4)

The choice principle aims to ensure users are able to choose. Choice promotes competition but users often have difficulty ingenuinely expressing their choice preferences because of cognitive biases (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021). Firms often use default options to increase the use of a service, for exampleby pre-installing it. Users usually stick to the default because they tend to stay with the status quo, indicative of the status-quo bias. However, the bias is not systematic as users often change their default settings, such as in relation to the choice of web browser or search engine (Akman, 2022).

Furthermore, the business models of digital firms are often based on a two-sided relationship, where they offer zero-price services to consumers to ease their enrolment,while offering paid services to businesses, generally in the form of advertising or marketing, which subsidises the free side. Consumers thus expect some online services, such as social networking or search engines, to be free. Most users are unwilling to pay even a small price to use them (Akman, 2022). Also, users often choose a free product over a paid-for one, even when the latter is of superior quality, indicative of the free effect (Ariely and Shampan’er, 2006). Accordingly, when platforms offer a choice between a paid version and a free version of their products or services, users tend to choose the free version because of their unwillingness to pay and the free effect.

Users also often have difficulties choosing when they face too many options and repeated choices – choice overload and consent fatigue (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021)

19

For instance, users express consent fatigue when they must consent to a consent banner on every website, making consent burdensome for users.

. Finally, users often encounter dark patterns and other misleading practices, such as dropping cookies to track the user’s web activity, even when users do not consent to cookies

20

Molly Killeen, ‘Le Figaro publisher fined €50,000 for GDPR violation’, Euractiv, 29 July 2021 https://www.euractiv.com/section/data-protection/news/le-figaro-publish….

.

The choice principle should be based on the following underpinning principles:

- Genuine: Users should have a real choice that takes into account users’ cognitive biases, such as status-quo bias.

- Unbiased: Users should be able to choose freely without manipulation or misleading practices, especially those arising from dark patterns.

- Not burdensome: Users should be able to choose easily between a few options,based on objective criteria to avoid choice overload, as shown with the Google Android choice screen for the choice of general search providers (Box 5).

- Unrepeatable: Users should only choose once at the appropriate time, such asduring setup, to avoid consent fatigue.

- Understandable: Users should understand their choice with the necessary description and consequence of the choice being given in simple, neutral terms and without unnecessary and unjustified warning messages 21 Gatekeepers should enable the use of alternative services to those of the gatekeepers (Article 5(7) and Recital 43 DMA). Gatekeepers should ensure businesses and consumers can access other CPSs without subscribing to a CPS (Article 5(8) and Recital 44 DMA). Gatekeepers should enable users to uninstall any software applications on the operating system. Gatekeepers should allow consumers to easily change the default setting of certain services by prompting a choice screen at the moment of the user’s first use (Article 6(3) and Recital 49 DMA). Gatekeepers should allow consumers to download third-party applications or software application stores. They should also enable third parties to prompt consumers to be the default service and to allow easily that change (Article 6(4) and Recital 50 DMA). .

Box 5: The Google Android choice screen for the selectionof general search providers

In 2018, the European Commission found that Google abused its dominant position by tying the provisions of its general search engine, Google Search, and web browser, Google Chrome, with its app store, Google Play, when licensing its mobile operating system, Google Android, to smartphone manufacturers

22

AT.40099 Google Android, 18 July 2018. The case is still pending before the European Court of Justice after the Court backed the Commission’s finding in the first instance C-738/22 P Google and Alphabet v Commission (pending).

. Following the Commission’s decision, Google changed its practice by offering a choice screen for the selectionof general search providers. The choice screen displays at the top the five primary providers,and then seven other providers based on market share data from the public source StatCounter. Participation in the choice screen is free of charge based on objective eligible criteria, after the dropping of an auction-based mechanism that would have remunerated Google

23

Android, ‘About the Choice Screen’, 12 June 2023, https://www.android.com/choicescreen/.

.

3.1.5 Flexibility (Principle 5)

Under the flexibility principle, users should be able to change and ease multi-homing when users use more than one service for the same purpose. Users often multi-home, for example by using a range of messaging services (Akman, 2022). However, they sometimes have difficulties in switching to or using actively another service. Indeed, switching might not be an available option– for example for downloading applications outside the Apple App Store – or might be burdensome because of the time and effort required to create an account

24

M.8124 Microsoft/LinkedIn, 6 December 2016, para. 345.

. When switching, users might even lose their data and connections, requiring them to rebuild their profiles again from scratch. Users also face cognitive biases that make switching more difficult, such as with pre-installed services

25

Ibid, para. 309.

. Observance of the flexibility principle should follow the underpinning principles set out below to minimise switching costs:

- Contextual: Users should be able to retain the context of their profile (eg data about posts, likes, comments, customer reviews, connections) when switching to another provider, to minimise the efforts required to create a new profile on the alternative provider’s platform, in line with appropriate laws, including the GDPR to protect the privacy of others.

- Easy: Users should be able to change easily from one service to another with minimum steps that would otherwise discourage switching.

- Frictionless: Users should be able to change without any restrictions, including technical restrictions.

- Free of charge: Users should be able to change without cost. When otherwise allowed, prices should be objectively justifiable

26

Gatekeepers should ensure that consumers can switch freely between software applications and services without undue restrictions (Article 6(6) and Recitals 53 and 54 DMA).

.

3.2 Monitoring

Gatekeepers are responsible for ensuring that they comply effectively with their obligations. They have the flexibility to implement compliance solutions. Our compliance principles can help gatekeepers implement their compliance solutions. They might even help third parties in proposing alternative compliance solutions to those of the gatekeepers to show to the gatekeepers and the Commission that other solutions exist. In this circumstance, compliance principles might be the baseline for a consensus between the solutions proposed by a gatekeeper and a third party when they engage together in a regulatory dialogue, as encouraged by the Commission

27

The European Commission (2023) has issued a template for the compliance report, which encourages regulatory dialogue between the Commission, third parties and the gatekeepers.

.

In this context, gatekeepers should show that the implementation of the compliance solutions is workable. Thus, they should provide in their annual compliance reports to the Commission methodologies, tests and any other relevant documents that provide evidence of a workable compliance solution (Article 11 DMA).

In addition, they should also put in place internal reporting systems thatmonitor that their compliance solutions work as intended once implemented. This system should enable gatekeepers to engage regularly with third parties and consumers in orderto identify and adapt their compliance solutions quickly to technical issues and cognitive biases (Carugati, 2023d).

Finally, the Commission should monitor that gatekeepers follow the compliance principles. They should do this by engaging regularly with gatekeepers, third parties and consumers before and after the implementation of the compliance solutions.

References

Akman, P. (2022) ‘A Web of Paradoxes: Empirical Evidence on Online Platform Users and Implications for Competition and Regulation in Digital Markets’, Virginia Law and Business Review 16(2), available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3835280

Ariely, D. and K. Shampan’er (2006) ‘How Small is Zero Price? The True Value of Free Products’, FRB of Boston Working Paper No. 06-16, available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.951742

Carugati, C. (2023a) ‘The Digital Markets Act is About Enabling Rights, Not Obliging Changes in Market Conditions’, Analysis, 6 September, available at https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/digital-markets-act-about-enabling-rights-not-obliging-changes-market-conditions

Carugati, C. (2023b) ‘The Difficulty of Designating Gatekeepers Under the EU Digital Markets Act’, Bruegel Blog, 20 February, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/difficulty-designating-gatekeepers-under-eu-digital-markets-act

Carugati, C. (2023c) ‘The antitrust privacy dilemma’, European Competition Journal 19(2): 167-190, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/17441056.2023.2169310

Carugati, C. (2023d) ‘The “pay-or-consent” challenge for platform regulators’, Analysis, 6 November, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/pay-or-consent-challenge-platform-regulators

CMA (2022) Online Choice Architecture How digital design can harm competition and consumers, Discussion paper, Competition & Markets Authority

CMA and ICO (2023) Harmful design in digital markets: How Online Choice Architecture practices can undermine consumer choice and control over personal information, Joint position paper by the Information Commissioner’s Office and the Competition & Markets Authority

Crémer, J., Y.-A. De Montjoye and H. Schweitzer (2019) Competition policy for the digital era, European Commission, Directorate-General for Competition

Crémer, J., D. Dinielli, P. Heidhues, G. Kimmelman, G. Monti, R. Podszun, M. Schnitzer, F. Scott Morton and A. de Streel (2022) ‘Enforcing the Digital Markets Act: Institutional Choices, Compliance, and Antitrust’, Policy Discussion Paper No. 7, Tobin Center for Economic Policy at Yale

Digital Competition Expert Panel (2019) Unlocking digital competition, HM Treasury, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

European Commission (2023) 'Template form for reporting pursuant to Article 11 of Regulation (EU) 2022/1925', available at https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-10/Article%2011%20DMA%20-%20Compliance%20Report%20Template%20Form.pdf

Feasey, R. and A. De Streel (2023) ‘DMA Output Indicators’, Draft Issue Paper, July, Centre on Regulation in Europe

McDonald, A.M. and L.F. Cranor (2008) ‘The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies’, I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, 2008 Privacy Year in Review Issue

OECD (2018) ‘Quality considerations in digital zero-price markets’, Background note by the Secretariat, DAF/COMP(2018)14, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OECD (2022) ‘Dark commercial patterns’, OECD Digital Economy Papers No. 336, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Thaler, R. and C. Sunstein (2021) Nudge: The Final Edition, Penguin