Italy's Atlas bank bailout fund: the shareholder of last resort

Italy’s new bank fund Atlas might be what is needed in the short run, but in the longer term the fund will increase systemic risk. What ultimately mat

This blog post was also published on Makronom.

In Greek mythology, Atlas the Titan was condemned by Zeus to eternally hold the weight of the sky on his shoulders. A mythological struggle that has recently made the news, thanks to the creation of a new Italian bank fund named after the titan, and facing the equally tough duty of sustaining the weakest pillars of the Italian banking system.

Several issues remain with the new fund which deserve discussion. First, the fund may avoid the need for bank resolution in the short term, but increases systemic risk in the longer term. Second, the role of the state is dubious and should be spelled out for reasons that go well beyond state aid considerations. Third, the extent to which this is also an initiative to preserve the Italian ownership of Italian banks is unclear.

The Issue

Italy’s bank fund was announced on 11 April, before Italian banks Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca undertake important capital increases. The fund is expected to raise 4-6 billion euros, and act as a backstop to shore up confidence in the Italian banking sector.

In practice, its mission is to “ensure the success of capital raising requested by the supervisory authority for banks that face market difficulties”, by acting as a subscriber of last resort. It also aims to buy mezzanine and junior tranches of securitized non-performing loans (NPLs).

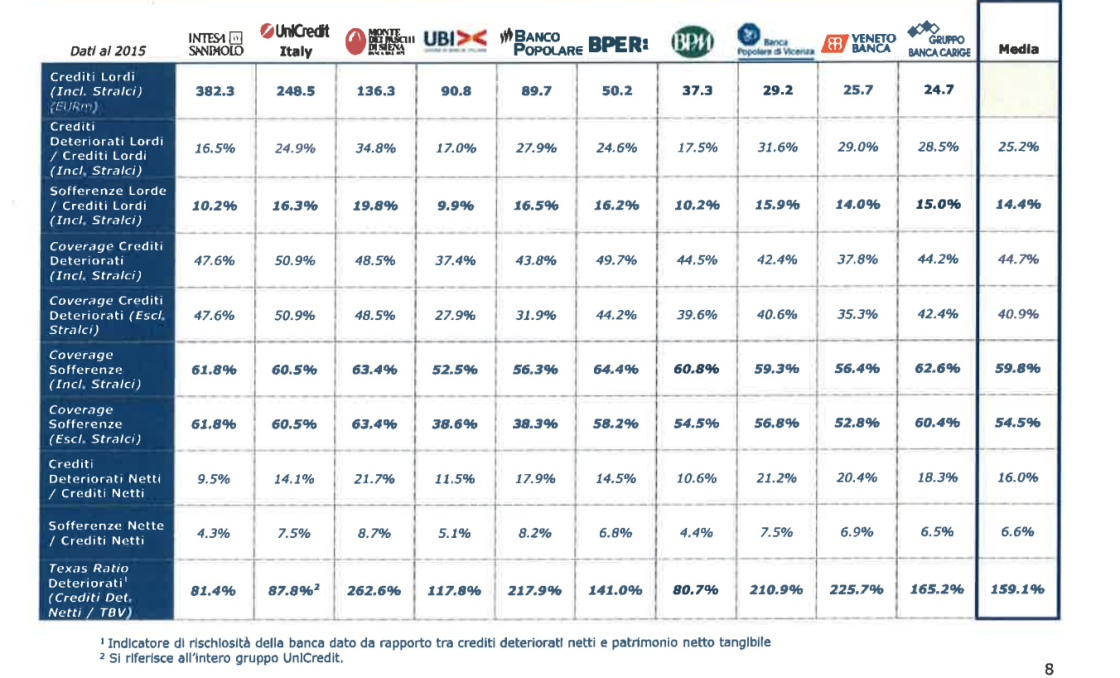

Out of the 360 billion euros of Italian NPLs, the more serious bad debt (“sofferenze”) accounts for 14% of total loans on average (about 200 billion euros), with a coverage ratio of 59.8% (see table 1).

Assuming a price of 20 cents on the euro (in line with the cases of previous resolution), banks would be covered for 79% of the nominal value of their impaired assets, while the remaining 21% would face a net loss of 42 billion euros on bad debts (or 2.6% of Italian GDP).

In perspective, it’s a much smaller amount than what other countries have pledged in support of their banking system, and had this happened years ago, the state could have covered it. But today the picture is different.

NPLs in Italian banks

Source: Atlas confidential draft leaked to Il Messaggero

Systemic re-shuffling

The systemic implications of the fund’s structure and role have been downplayed in the debate. After the two episodes of bank resolution conducted last year (discussed here and here), there is one fact that could not be clearer: in a country where about a third of bank bonds is held by the household sector, even a limited bail-in can have painful consequences for people’s lives.

A leaked draft of the Atlas project suggests that the initiative stems from fears of the systemic implications if Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca failed to raise enough capital. If this were to happen, the document warns on page 2, there would likely be bank runs due to depositors’ worrying about bail-in, increases in the cost of funding, losses on direct and indirect bank exposures, losses on households’ investment portfolios including bank debt, and negative effects for the real economy.

Salvatore Rossi, Director General of the Bank of Italy, recently stated that Atlas will reduce systemic risk, by avoiding “fears of a ‘domino effect” due to the difficulties of individual banks. However, the structure of the fund would suggest otherwise.

The fund will be mostly financed by Italian banks and privately held institutions. Recent reports suggest that the two largest Italian banks, Intesa and Unicredit, will contribute 1 billion euros each, one additional billion will come from other banks, 500 million from banking foundations, 500 million from the publicly controlled Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, and the rest from Italian insurance companies.

By acting as a shareholder of last resort for those banks that are too weak to raise capital on the market, the fund effectively prevents bank resolution (and its consequences) in the short run. But it does so by piling up risk onto the balance sheets of a banking system that is already very interconnected, and that at present retains areas of weakness.

It’s hard to see how this would reduce the risk of a domino effect in the long term. Scepticism is reflected in the assessments of Fitch and S&P, which both point out that the fund increases the exposure of stronger banks to weaker banks, with negative prospects for the stronger banks’ creditworthiness.

Concerning confidence - which the fund is expected to increase by acting as a buyer of last resort - the effect is at best dubious. Ideally, a backstop should be reassuring enough for it never to be used, but considering the sense of urgency surrounding Atlas, this is unlikely to be the case.

In fact, recent news reports suggest that investor demand for shares issued by Banco di Vicenza is poor, and that the total unsold portion could total no less than 1 billion euros. Atlas will cover the gap, but should a capital raise that succeeds only thanks to the unconditional commitment of a buyer of last resort be considered a “successful” capital raise? And is it reasonable to expect that increasing exposures of stronger banks to weaker banks will enhance confidence in the health of the Italian banking system as a whole?

What’s made in Italy, stays in Italy

The extent to which this fund is aimed at preventing foreign takeovers of Italian banks is unclear. On March 29 US private equity fund Apollo offered to buy a majority stake in Italian bank Carige as well as the bank’s 3.5 billion euros of NPLs, and media reports suggest the bid was also viewed favourably by the ECB. A recent Repubblica article suggested that the objective of the bank fund “is also to prevent the arrival of foreign funds, able to put on the table enough resources to buy NPLs and recapitalise the banks acquiring control, as Apollo is trying to do with Carige”. Similar interest was expressed by US fund Fortress for Banca Popolare di Vicenza, but the idea was abandoned earlier this month.

Italian finance minister Padoan speaking in Washington at the Peterson Institute of International Economics on April 14 dismissed this as “gossip”, arguing that the fund is not aimed at preventing foreign entry, but to prevent the dismissal of Italian banks’ assets at fire sale prices.

As always, the key question is what the market price for these assets is. The fund may not have the explicit objective of limiting foreign entry, but if the “fire sale” prices at which foreign investors are willing to invest reflect actual market value, than by buying at higher prices the fund keeps out foreign investors and subsidizes the banks shedding those assets. Perhaps more importantly, it achieves this by buying assets at a higher cost than they are worth, and funding this mostly within the rest of the Italian banking system.

The argument in favour of this is that if the NPL scheme succeeds and growth picks up, then the value of these assets will recover enough to make the operation profitable, so the fund buys banks the precious time they need for their assets to become appealing to foreigners at a higher price.

The obvious counterargument is that the Italian banking sector has spent the last 5 years trying to buy this time, with the result that it now has to set up Atlas to avoid resolving those banks that should have recovered but did not. The experience of this delayed clean-up would suggest that more time is not always enough, and that this is a risky bet. An important test for Atlas will be whether foreign investors will eventually invest in it.

Unclear nature

While there have been reports that the fund is “government-inspired”, the Italian government has stressed its private nature (see minister Padoan here, the government website here). This is key to prevent the fund’s operations from being classified as state aid by the European Commission, but it also matters in relation to the structure of the recently approved state guarantees scheme for NPLs, known as GACS in Italian.

The GACS scheme foresees a state guarantee on the less risky senior tranches of securitized NPLs, but before the guarantee can be activated, 50% of the less senior tranches need to be placed with private investors. The market appeal of these riskier tranches is low, or rather the market price could be very different from the value at which the NPLs are accounted for on banks’ balance sheets, which would translate into impairments and consume capital.

So the guarantee scheme for Italian NPLs runs the obvious risk of stillbirth unless Italian banks pool their funds together into a private fund and buy a significant part of the junior products themselves, which is precisely what Atlas will do.

Yet, if this is supposed to be a fully private initiative, it is not clear why it should include a 500 million euro contribution from the Italian National Promotional bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, which is a joint-stock company under public control.

The role of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) should be clearly spelled out. The rationale for transparency goes well beyond state aid considerations. A first reason is that the fund will buy unsold shares from those banks that have been asked to raise capital by the supervisor: the involvement of a publicly controlled institution as a buyer of last resort could cast doubts on the strength and impact of supervisory action.

Take the example of Banca Popolare di Vicenza, which is raising capital for the third time in three years. Normally, if a supervisor requests that a bank raises capital and the bank fails to do so the bank is put into resolution.

In the Italian case, if Banco Popolare di Vicenza fails to raise capital later this month, the fund (in which CDP participates) will step in to ensure that the resolution threat is removed regardless from the market outcome. In this scenario, the strength of supervisory action is reduced.

Moreover, avoiding a bank resolution will also prevent the change in governance structure that the resolution authority can demand from a bank. Considering that the previous cash calls of Banca di Vicenza are now under investigation, after an ECB inspection revealed that the bank had loaned money to customers to buy the shares and that in some cases managers allegedly signed letters guaranteeing the bank would return or repurchase the shares, a change in governance appears to be highly warranted.

A second reason is that the fund will become shareholder of relatively weaker banks in the system and buy relatively riskier NPLs tranches. The rationale for involving into such operation the CDP, which manages a large share of Italian savings, should be transparently discussed.

Conclusion

The Atlas fund has a heavy task, although probably not as heavy as that of its mythological namesake. In the short run, it might be what most commentators have described: an imperfect but needed second-best way to avoid bail-in and resolution, matching repeated calls from the Bank of Italy for a revision of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) framework after Italy negotiated and approved it.

However, by acting as a bank shareholder of last resort the fund increases systemic risk in the longer term, weakening the stronger banks and involving a publicly controlled institution whose main source of funding is postal savings into a rather risky venture.

While it’s unclear whether the aim is to keep foreign capital out of the Italian banking system, what ultimately matters is how this initiative will affect (or avoid affecting) the quality of bank governance, a key issue for the future resilience of the system. Regardless of whether we think that keeping weak banks alive at all costs is a good idea, the idea of such a shareholder of last resort appears at odds with the aim of making progress towards a solid European Banking Union.