Has the European Central Bank transformed itself into a hedge fund?

Some observers have accused the European Central Bank (ECB) of having transformed itself into a hedge fund because of the purchases of government secu

Some observers have accused the European Central Bank (ECB) of having transformed itself into a hedge fund because of the purchases of government securities from stressed countries under the Securities Market Program (SMP)[1].

The accusation of course does not take into account, or does not believe, the argument made by the central bank that the purchases were needed to counter the fragmentation of the euro area financial market brought about by the crisis and the ensuing impairment, or even break down, of the transmission of monetary policy. In a nutshell, the argument of the ECB was that its ability to guide, through its control of the short-term interest rate, the cost of bank lending relevant for the economies of the different countries of the euro area was substantially impaired by the diverging behaviour of the yields on government securities in the periphery with respect to the core. For instance bank rates on small loans (up to and including EUR 1 million) have been on average 200 basis points higher in Spain than Germany during the last 10 months, given that the yield of Spanish government securities attracted Spanish bank rates up while that of German government securities attracted German rates down. And, of course, this is the wrong differentiation of monetary policy, given that Spain is in a recession, while unemployment in Germany is at historically low levels.

Whether one wants to follow or not the ECB reasoning that its purchases were dictated by macroeconomic and not investment reasons, like the ones of a hedge fund, it is interesting to ask what have been the financial consequences of the purchases: did the ECB loose or make money with its purchases of government securities from stressed jurisdictions? The question may get even more interesting for those who are convinced by the argument of Milton Friedman that only interventions that make money for the central bank are right from a macroeconomic point of view[2].

The recent publication from the ECB of the split per country of its purchases under the Securities Market Program, together with the available data on the weekly purchases and the difference between the market prices prevailing when the purchases were made and those prevailing in March 2013 allow estimating, albeit with some inevitable imprecision, whether the central bank has lost or made money with its purchases[3].

Table 1

|

Issuer country |

Outstanding amounts |

Average remaining maturity (in years) |

Share of total holdings of each round[4] |

|

|

Nominal amount (EUR billion) |

Book value[1] (EUR billion) |

|||

|

Ireland |

14.2 |

13.6 |

4.6 |

20.6% |

|

Greece |

33.9 |

30.8 |

3.6 |

46.7% |

|

Portugal |

22.8 |

21.6 |

3.9 |

32.7% |

|

Spain |

44.3 |

43.7 |

4.1 |

30.6% |

|

Italy |

102.8 |

99.0 |

4.5 |

69.4% |

|

Total |

218.0 |

208.7 |

4.3 |

|

Source: ECB

In this exercise we estimate the profits that the ECB would make if it were to sell its holdings of bonds purchased under the SMP at the current market value (as of March 1th, 2013); we thus estimate profits according to a “mark to market” approach. This is not the accounting convention followed by the ECB, which uses a “held to maturity” convention, which implies that the bonds are not sold and therefore are reimbursed at par at maturity, unless some bonds were defaulted. The situation is more complicated as regards the Greek bonds, because the ECB was exempted from the so-called Private Sector Involvement but has committed to indirectly return the profits it will realize on Greek bonds to the Greek government.

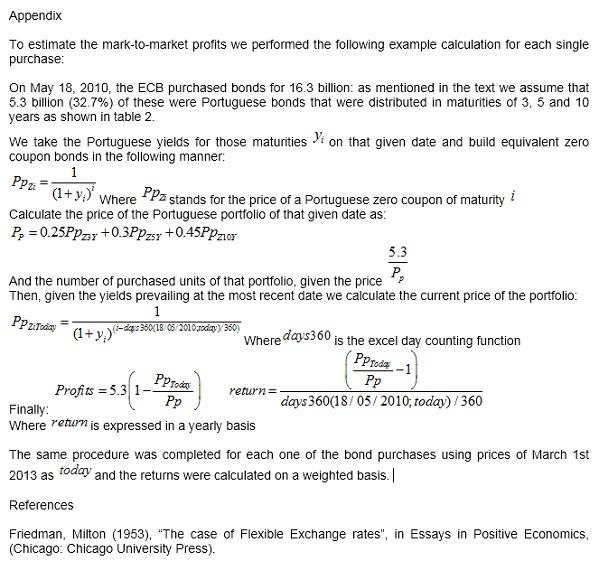

In order to carry out our estimate, given that the ECB has not released exactly which bonds were purchased at each date, but only the total weekly amount of SMP purchases, the following assumptions were made:

· Each week the ECB purchases are assumed to have been made according to the reported shares of total holdings for each round, reported in table 1. For instance, during the second week of May 2010, the ECB purchased a total of 16.3 billion euro area bonds and it is assumed that 7.6 billion (46.7%) of these were Greek bonds, 5.3 billion (32.7%) Portuguese bonds and 3.4 billion (20.6%) Irish bonds.

· To match the average remaining maturity reported by the ECB at the end of 2012, each week the ECB is assumed to have distributed its purchases according to the maturities in the following table:

Table 2

|

|

3Y |

5Y |

10Y |

|

Greece |

25% |

35% |

40% |

|

Portugal |

25% |

30% |

45% |

|

Ireland |

15% |

30% |

55% |

|

Spain |

45% |

30% |

25% |

|

Italy |

37.5% |

32.5% |

30% |

Table 3 reports our estimate of “marked to market” profits, calculated comparing market prices[5] at the time of the purchases with current prices.

Table 3

|

|

Profits (bn euro) |

Yearly return |

|

Greece |

-6.2 |

-6.6% |

|

Portugal |

2.3 |

3.7% |

|

Ireland |

3.7 |

10.0% |

|

Spain |

6.4 |

10.9% |

|

Italy |

8.0 |

5.9% |

|

Total |

14.3 |

4.8% |

In conclusion, if one wants to see the ECB has a hedge fund this has been a successful one, with profits of 14.3 billion over an investment of 222 billion, equivalent to 6.4 per cent, taking into account capital gains and coupon income, recently published by the ECB. Capital gains on the purchases of Italian, Spanish, Irish and Portuguese securities have in fact more than compensated the losses on Greek securities. If one believes the argument of the ECB, that it carried out the interventions for macroeconomic reasons and is further convinced by the reasoning of Friedman, that financial and macroeconomic reasons coincide, then the evidence is that the interventions under the Securities Market program were, so far, successful also from a macroeconomic point of view. Of course, it is obvious that the ECB has incurred additional risk with its purchases, but this should surprise no one, as risk and return are necessarily interrelated, both in investment and in macroeconomic operations.

References

Friedman, Milton (1953), “The case of Flexible Exchange rates”, in Essays in Positive Economics, (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

[1] Of course, the relevant entity is the Eurosystem, comprising the European Central Bank as well as the 17 National Central Banks of the countries of the euro area. However, for simplicity, the term ECB will be used as a short cut for Eurosystem.

[2] Milton Friedman referred to foreign exchange interventions, but the argument applies in analogy to any kind of interventions, Friedman Milton (1953).

[3] The underlying spread sheet is available on request from the authors.

[4] The SMP was started on May 10th 2010, purchasing Irish, Portuguese, and Greek securities and continued until the beginning of March 29th 2011 (first round). Then it paused and started again on Aug 7th 2011 with purchases of Italian and Spanish securities until September, 6th 2012 (second round).

[5] Not having precise information about the bonds that were purchased, these estimates were made calculating the implicit price of equivalent zero coupon bonds at each given date using the yields of sovereign bonds of 3, 5 and 10 years maturities. For more information see the appendix.