The G7 is dead, long live the G7

The summit in Charlevoix left behind a Group of Seven in complete disarray. The authors think that the G-group, in its current formulation, no longer

The summit on June 8th and 9th in Charlevoix, Canada, left behind a Group of Seven (G7) in complete disarray. Following days of tense negotiations, the G7 painstakingly managed to hammer out a joint communique, only to see US president Donald Trump withdraw from it shortly after the summit.

Commentators around the world have been quick to blame President Trump for undermining the world order or pushing the G7 into increasing irrelevance. However, in this latest fiasco, we see a mere vindication of our long-held view that the G-group, in its current formulation, no longer has a reason to exist, and it should be replaced with a more representative group of countries (O’Neill and Terzi, 2014a).

The G7 was, for many years, an effective forum for dealing with major pending issues, having first met in 1976. Canada and Italy joined the original G5 (US, Japan, France, West Germany and the UK), who had previously come together earlier in the decade to deal with global economic emergencies such as the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement and the 1973 oil crisis.

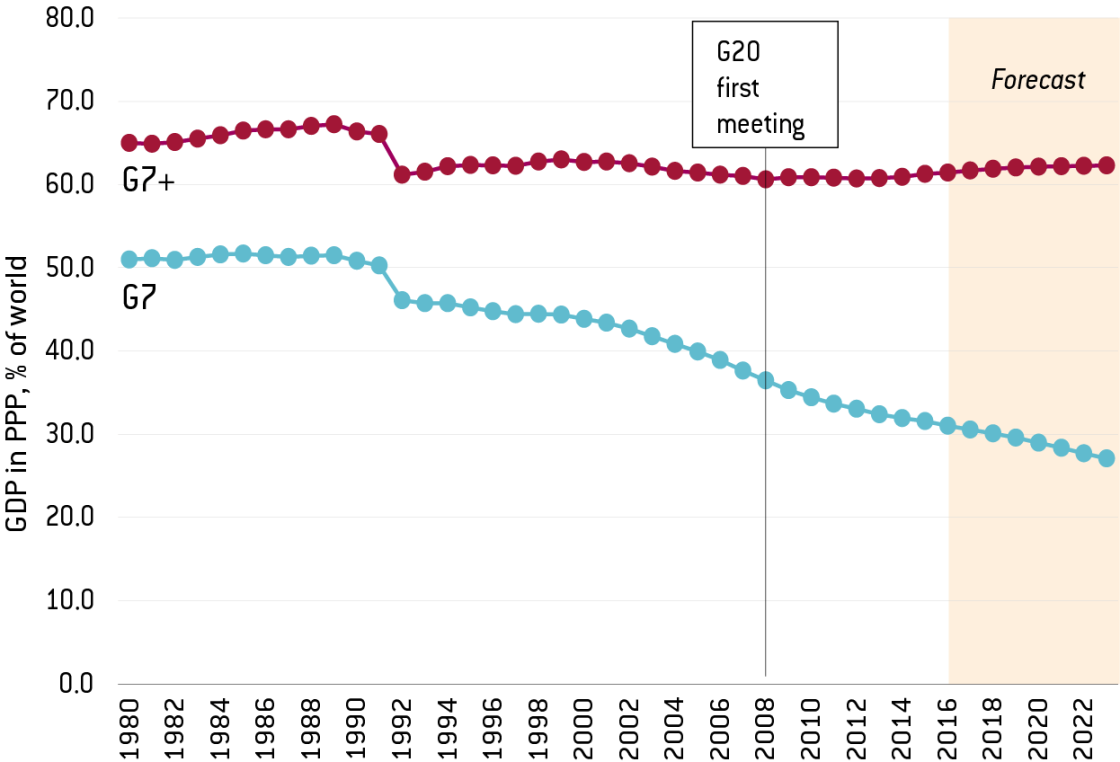

At the time, the G7 countries represented roughly 50% of global GDP (see Figure 1). However, as time went by, this share has been on a constant downward trend, especially due to the rise of China. Today, the G7 countries represent around 30% of global GDP, and IMF forecasts suggest this number will further contract going forward.

Figure 1. GDP commanded by current G7 countries, and revised G7+

Notes: 1992 time series break due to the inclusion of former USSR countries in the database

Sources: own calculations based on IMF WEO

As a consequence of this tectonic shift, it should come as no surprise that in 2008, when a global fiscal stimulus was needed to counteract the Great Recession, the matter could not be dealt with within this setting, and the G20 (as we know it today) was first established. While successful at the time, the G20 has since then lost decisional momentum (Angeloni and Pisani-Ferry, 2012).

Against this backdrop, in 2014 we ran a survey of G20 Sherpas (the high-level advisors of heads of state or government) to understand their perception of the G20’s workings and the potential for global governance reforms.

Faced with a G7 that was not representative of the new world order, and a G20 that was too big and heterogeneous to make decisions when not mired in deep crisis, we proposed the creation of what we then called a G7+ that would replace the current G7 (O’Neill and Terzi, 2014b). In the new G7+, France, Germany and Italy would be replaced by a common euro-zone representative. This would make space for China and India. Canada would be replaced by Brazil. The rest would remain unchanged (Table 1).

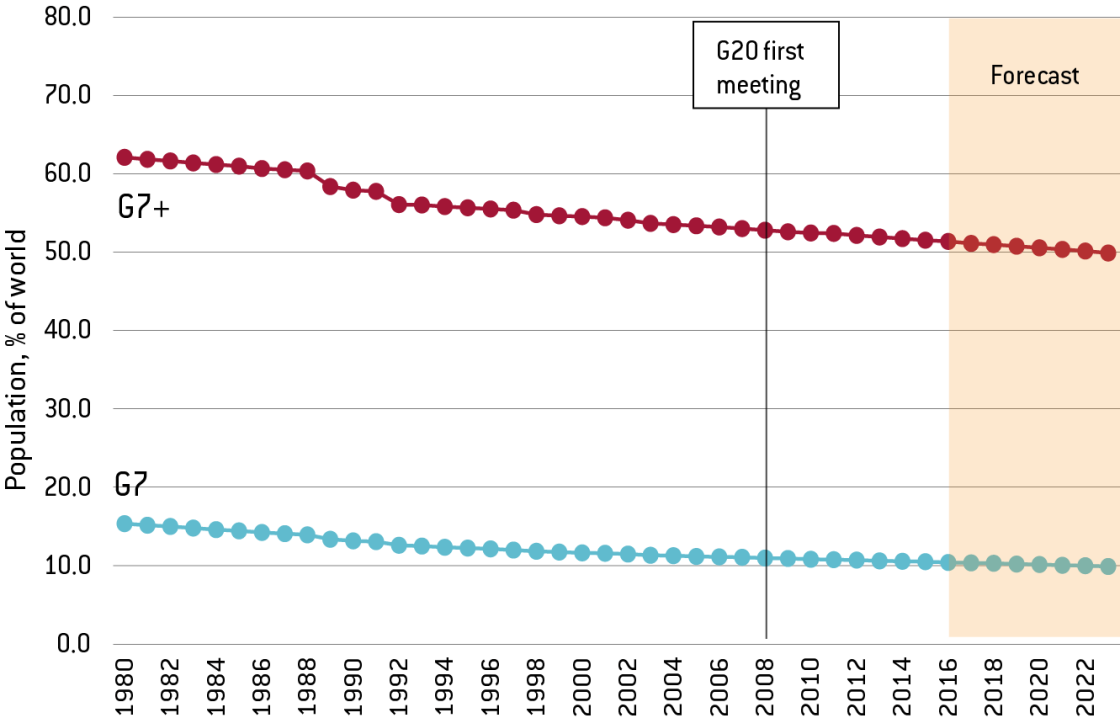

As described in Figure 1, this group would be much more representative in GDP terms. As a matter of fact, it would have represented largely a constant share of world GDP since the 1980s, hovering just over 60%. This also remains true looking ahead, based on IMF forecasts. Crucially, and in contrast to the G20, the G7+ would achieve this result without adding seats around the table and complicating decision-making. Also, in population terms, the new G7+ would be much more representative than the current G7, whose countries cover just over 10% of global population (Figure 2).

Crucially, the G7+ would provide leadership and fast-paced decision-making on economic and financial issues of global relevance – but should not replace the G20, which remains an important avenue for discussions of all other issues that call for higher representativeness, ranging from terrorism and food security to tax avoidance and climate change.

Figure 2. Population represented by current G7 countries, and revised G7+

Sources: own calculations based on IMF WEO

At the time of our first proposal, G20 Sherpas from non-G7 countries saw the move as reasonable, but argued that this was feasible only if the West were to move first. On the other hand, G7 country representatives made the point that even if representativeness is low, it remains desirable to have a forum for like-minded democracies. While this argument already appeared weak at the time, the latest developments make this view even more untenable.

Regarding the euro-area countries, we made the point at the time that giving up their seat and having a joint representative would send a clear signal in terms of commitment to the common currency. In light of Italy’s recent financial storm, this seems even more pressing nowadays than it was back then. Moreover, these countries already have a common trade and monetary policy, and soon potentially a joint defence force. It was indicative that when the new Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte mentioned at Charlevoix that economic sanctions on Russia should be relaxed, German Chancellor Merkel’s reply was that they should have spoken about that earlier (in a European setting).

President Trump might well have scrambled decades of world order for the wrong reasons through his “America First” agenda. However, the world has been changing fast and the G7, as it stands today, looks like a relic of the past. The earlier western countries realise this, the faster the world will achieve a better, more efficient, more representative global governance.

Bibliography

Angeloni, I. and Pisani-Ferry, J. (2012), “The G20: Characters in search of an author”, Bruegel Working Paper, 2012/04.

O’Neill, J. and Terzi, A. (2014a), “Changing trade patterns, unchanging European and global governance”, Bruegel Working Paper, 2014/02.

O’Neill, J. and Terzi, A. (2014b), “The twenty-first century needs a better G20 and a new G7+”, Bruegel Policy Contribution, 2014/13.