Fact of the week: A spam newsletter caused a bank run in Bulgaria

It’s been a tense week in Bulgaria. Two bank runs occurred last week, with depositors withdrawing the equivalent of 10% and 20% of the assets held by&

It’s been a tense week in Bulgaria. Two bank runs occurred last week, with depositors withdrawing the equivalent of 10% and 20% of the assets held by two important national banks. An emergency line of 3.3bn Bulgarian levs (€1.7bn) was approved by the European Commission on Monday, and tensions in the country seem to have eased since then. The modalities and motives of this mini financial crisis are not entirely clear yet, but it seems to be deeply rooted in a long-standing domestic business and political feud.

It all started last week. After a run by depositors, the Bulgarian National Bank took control of the country’s fourth lender, Corporate Commercial Bank (KTB). The operations were frozen, the directors suspended and the bank put under special administration, in the attempt to stop what the Central Bank described as “an attempt to destabilise the state through an organised attack against Bulgarian banks”.

Two days later, the bank has been nationalised, but it was not enough. Tensions spilled over from KTB to First Investment Bank (FiB), an even bigger domestic bank. According to the Financial Times, depositors withdrew 800m lev (about $556m) on Friday from First Investment Bank, and funds appear to have been moved to the foreign-owned banks in the country.

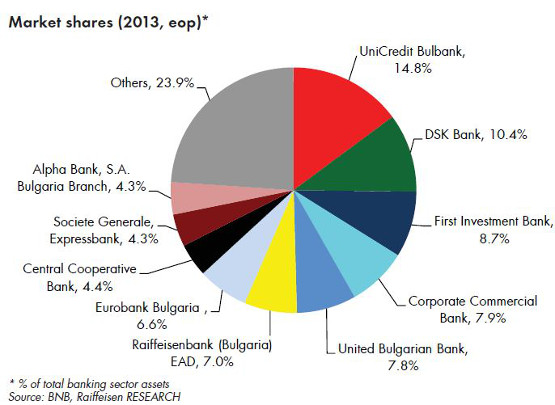

The Bulgarian banking system is in fact dominated by foreign lenders, especially Italian Unicredit, Hungarian DSK, Austrian Raiffeisen (figure 1).

Source: Wall Street Journal

The worsening of this situation triggered the introduction of a set of emergency measures by the Central Bank and the approval by the European Commission of a 3.3 billion levs (€ 1.7bn) credit line to ensure the necessary liquidity support to the banks. Sources quoted by the FT suggest that 1.3 Lev have already been raised on Monday through a special bond issue, mainly covered by foreign banks.

In its press release, the Commission stressed that that Bulgaria's banking system is: "well capitalised and has high levels of liquidity compared to its peers in other member states". So how and why were these two banks exposed to a run?

Concerning the “how”, the Bulgarian run is interesting because it basically shows how a bank run could look like in the tech and social networking era. Both the government and the central bank have in fact claimed that the run was ignited by a “cyber attack”, for which six people have already been arrested.

According to the Bulgarian National Security Agency (see here, for a reporting in English), an investment company that “built a network of associated companies for marketing services” that was used to diffuse panic by means of an alert, uncomfortably titled “Information Bulletin of on the Risk of Deposits in Bulgarian Banks”. The “bulletin” claimed – Bloomberg reports – KTB was undergoing a liquidity shortage. The message apparently also said that the government deposit guarantee fund was under-capitalised to meet possible repayments, that banks could go bankrupt and that the peg of the currency with the euro could be broken.

Allegedly, the alert was diffused by text, email and even Facebook messages, thus ensuring a very widespread outreach. In a country that in 1997 underwent a very serious banking crisis featuring all these characteristics – whose memory is still fresh – this was enough to spur panic.

Source: Reuters

Concerning the why, the story is extremely complicated. Different interests prevail according to different versions, making it quite difficult to reach a clear conclusion, but it certainly seems to have little to do with economics and a lot to do with politics.

KTB bank – the first to all in trouble last week – is the ultimate hotspot where business feuds, personal issues, corruption, political uncertainty, tensions with Russia and pressures from Bruxelles all come together into an explosive mix. KTB bank is known to have very strong and complex political connection. According to the Financial Times, 30% of KTB is controlled by Oman and a 10% by the Russian bank VTB. The largest shareholder owning a larger than 50% stake (which, incidentally, will be written off as a consequence of the state recapitalisation) is Tsvetan Vassilev, linked to the ruling party. Several sources, including New York Times and Financial Times attribute the bank run to the unfolding of a complicated “feud” between Tsvetan Vassilev and Delyan Peevski, another controversial prominent Bulgarian businessman owner of a media empire as well as Member of the Parliament.

The two fellows’ businesses appear to share a number of connections. The tycoon’s empire is in fact reportedly built on loans approved by the now-troubled KTB bank itself. At the same time, the successful expansion of KTB bank is partly due to the fact that the bank was able to attract an extremely large amount of deposits from state-controlled companies, offering at the same time exceptionally high interest rates on retail deposits.

This “business model” had caught government’s attention last year already, leading to a strong regulatory reaction. In May 2013, in fact, a law was approved according to which those companies in which the government had a stake of more than 50 per cent should diversify the allocation of their deposits, with a maximum of 25 per cent per bank.

Bulgarian news reports Prime Minister Marin Raykov as saying that in 2013 54 per cent of state-owned companies’ deposits were held by one bank. While Raykov declined to name the financial institution, the Sofia Globe argues that the most likely guess – and one widely made by Bulgarian media – is Corporate Commercial Bank (KTB).

Several analysts’ and news reports attribute the bank run and last week mini-crisis to the unfolding of a latent war between Peevski and Vassilev. In particular, the trigger of the crisis at KTB (controlled by Vassilev) has possibly been the withdrawal of a large amount of money by Peevski.

According to this version of the story, the money would have been moved exactly to FIB, which would have later come under pressure when allies of Vassilev retaliated by spreading rumours about its solidity. While these can be considered speculations, the relationship between the two businessmen is certainly not good now, and they repeatedly accused each other of various wrongdoings.

On top of the internal feud, the run comes at the end of a period during which political uncertainty has been mounting in Bulgaria. This is partly due to the fact that Bulgaria – which is a major transit route for Russian gas – has been caught in the crossfire between Russia and Europe over the country’s participation in South Stream.

The Prime Minister announced his resignation and the country will most likely see anticipated elections, while Standard & Poor’s cut Bulgaria’s sovereign rating to triple-B minus, citing political instability as the main concern. Such nervous and precarious political environment, coupled with the fact that Bulgaria is one of the countries most affected by corruption, offers little protections against the unfolding of business and political feuds like the one that appears to have been behind the bank run of last week.

Luckily, contagion seems to have been stopped before turning these embers could ignite a more serious fire.