Don’t put the blame on me: How different countries blamed different actors for the Eurozone crisis

Why did the eurozone have such difficulties coming to terms with its own shortcomings? The authors believe they have found part of the answer, through

Recovering from a crisis is never easy. That’s as true for individuals as it is for entire nations. Often some painful soul-searching is involved, associated with learnings for life. Something’s got to change – it’s this attitude that, eventually, triggers progress. And then there’s the eurozone.

Eight years after the sovereign debt crisis started with the near-bankruptcy of Greece, Portugal, and Ireland, member states still cannot agree on a comprehensive set of reforms. With the exception of France’s Emmanuel Macron, they even seem to have stopped trying.

Currently, Germany is consumed by its own political paralysis. Italy could be electing a populist government in a matter of weeks. Spain is preoccupied with the separatist movement in Catalonia. A strong cyclical upswing may finally have caught on, but the currency area seems incapable of turning the aftermath of the crisis into progress. The fundamental question is, why?

We’ve been asking ourselves many times in recent years, why the eurozone had such difficulties coming to terms with its own shortcomings. In a joint research project, which has led to a Policy Contribution, we believe that we’ve found part of the answer: Europeans do not share common political narratives. As a consequence, it seems impossible to come up with a common policy agenda. Or as Lenoid Bershidsky noted: “The eurozone is the only currency union in which there is no single constituent public. Instead, there are a number of national filter bubbles.”

Measuring narratives

Since the non-existence of a pan-European public sphere has been a much-lamented obstacle to European integration, the notion of separated publics may not sound too surprising. But we’ve developed an approach that enables us to measure and compare narratives across countries over time.

Applying novel text-mining techniques, we analysed more than 51,000 crisis-related articles that appeared in four leading newspapers from the four biggest euro-zone countries – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – over a period of 10 years. Elite newspapers are often used in communication studies, as their reporting patterns represent wider parts of the media sphere and of public opinion in general. The four papers we chose – Süddeutsche Zeitung, Le Monde, La Stampa, El País – are all centrist or slightly left-of-centre publications and share a fundamental pro-Europe stance. Thereby, we strove to focus on national differences rather than ideological ones. Note that our analysis is not meant as a critique of some kind of media bias, but we treat these leading publications as a proxy for the prevailing sentiment in the countries concerned.

The algorithmic approach yielded a number of “topics” (i.e. categories in which articles of similar content and framing are clustered) for each paper, which focus on institutions (such as the “troika”), specific euro-zone countries, or the respective national government, – as well as what we call “systemic topics” that contain opinion pieces, commentary, or book reviews, and which shed light on the overall mood and prominent arguments. In each of the papers, we found a distinct set of crisis-related topics, but they are all of a different composition.

A blame game?

To get a grasp on the question of which entities are being blamed for causing – or prolonging – the crisis, we augmented the algorithm-based content analysis with a “blaming dictionary” (a list of 140 words that attribute responsibility to entities, persons, institutions, systems).

Applying this approach, we constructed a measure of “accumulated blame” – i.e. the sums of blame values of the topics present in the discourses in each country, over the entire period from 2007 to 2016. This approach is meant to capture the exposure each public has had to a certain perspective on the euro crisis’ causes and its possible remedies, thereby producing a measure of political “priming” each country has experienced.

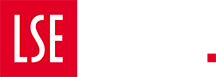

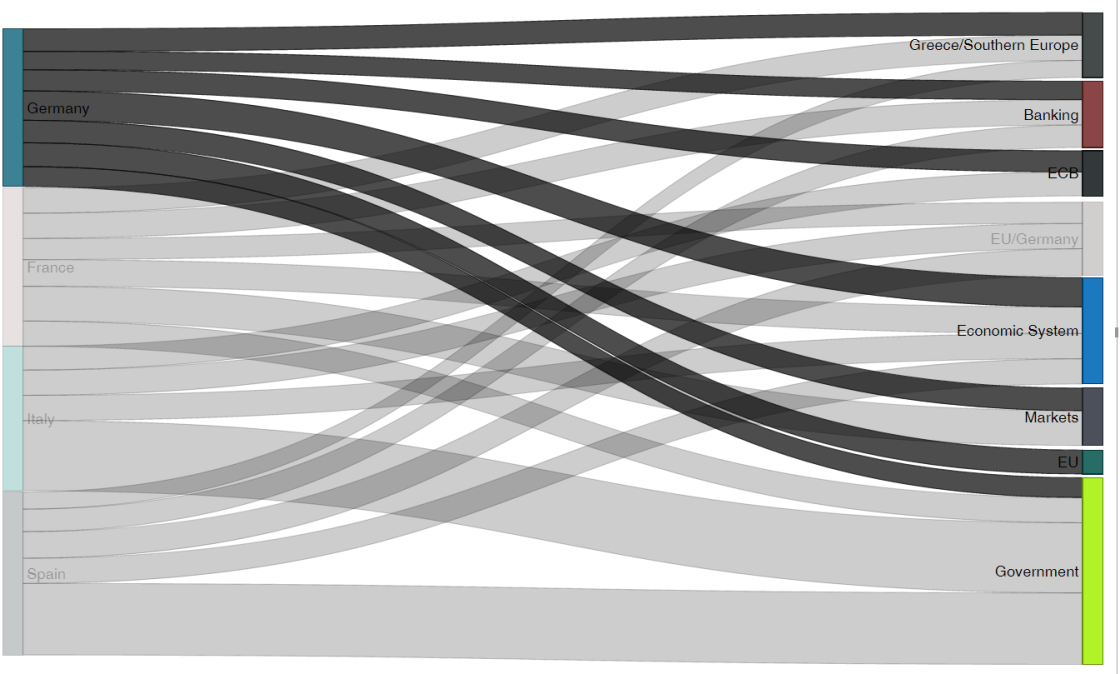

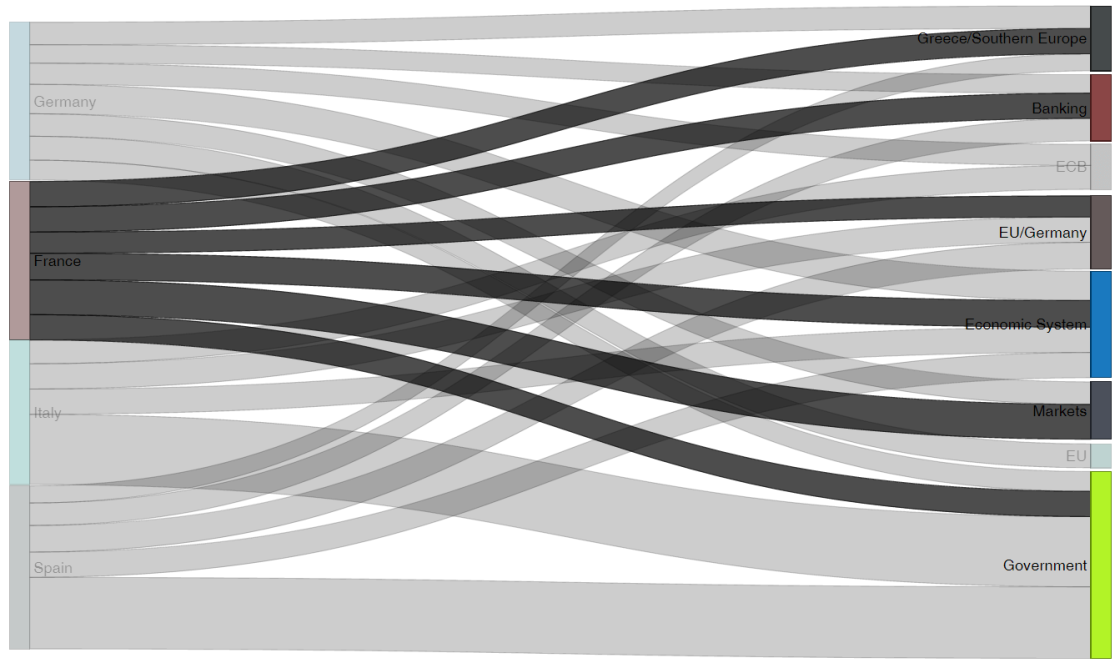

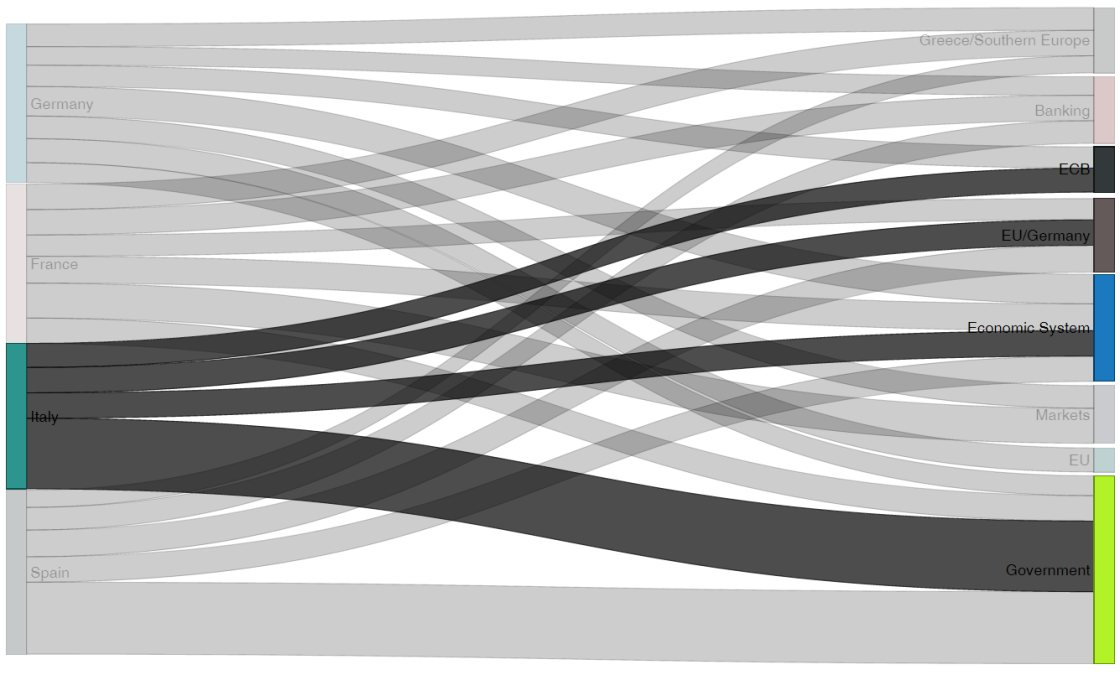

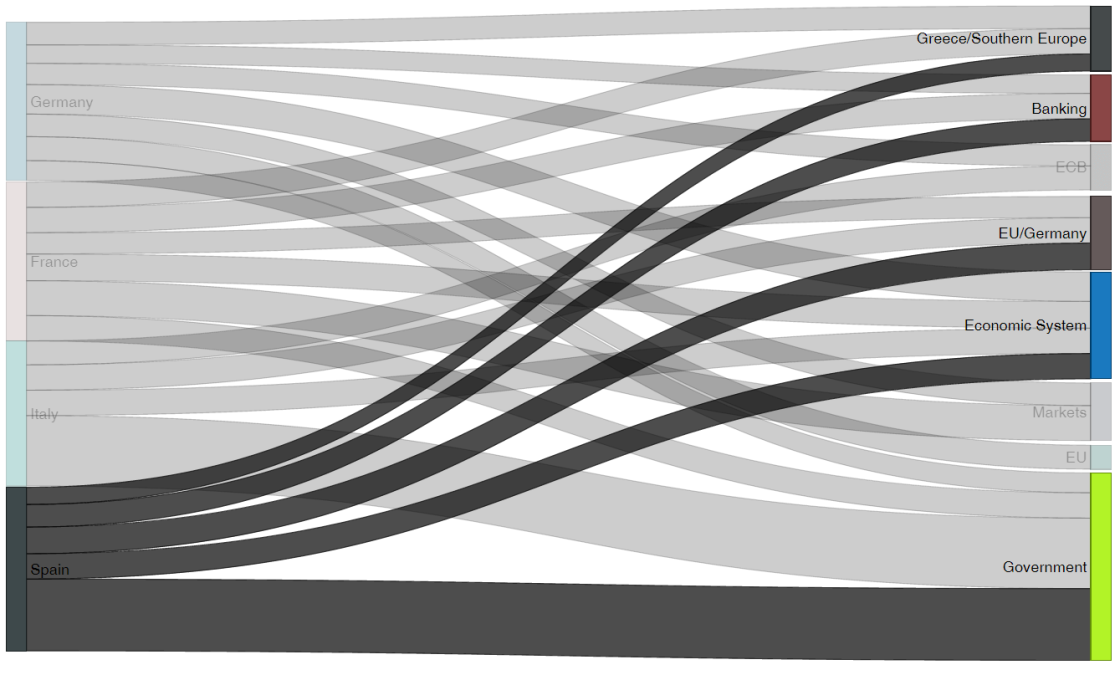

To visualise the results, the accumulated blame values are shown in the figures below. On the left-hand panel, the countries are displayed; on the right-hand side, the blamed institutions are displayed. The intensity of blame is reflected in the width of the lines.

Figure 1: “Blame” in the German Süddeutsche Zeitung

In Germany’s leading paper Süddeutsche Zeitung (Figure 1), accumulated blame for the euro crisis and its aftermath is more or less evenly distributed across the spectrum of possible culprits – displayed by the almost similar width of the lines – the sole exception being the German-inspired stance of EU institutions (EU/Germany), which is all but absent from our lists of targets for blame.

The picture for France (Figure 2) looks almost similar at first sight, but selected blind spots can be detected – particularly regarding the ECB, which is absent as a distinct topic.

Figure 2: “Blame” in France’s Le Monde

Italy’s La Stampa (Figure 3) and Spain’s El País (Figure 4) show rather different patterns. Both countries emphasise the responsibility of their own respective government, shown by the greater width of respective lines. Other aspects, though, remain under-exposed – such as Greece, banking and financial markets in Italy, and, particularly in Spain, the ECB and the EU.

Figure 3: “Blame” in Italy’s La Stampa

Figure 4: “Blame” in Spain’s El País

Roughly put, we found varying crisis narratives in each of the four newspapers, which can be summarised as follows:

- Germany’s leading paper Süddeutsche Zeitung blamed everyone but Germany, the chief suspects being Greece and the ECB; it stresses the need to get back to a perceived status quo of stability and fairness, as associated with Germany’s post-war model of a social market economy.

- France’s Le Monde blamed everyone including the French political class, but largely refrained from criticising European institutions such as the European Commission and the ECB.

- Italy’s La Stampa sees Italy as the victim of unfortunate circumstances – including the EU austerity measures promoted by Germany – and Italy’s own politicians.

- Spain’s El País primarily blames Spain itself for misconduct during the boom years preceding the crisis.

So, how do we proceed?

The picture of differing public spheres shows that each euro-area country faces different

pressures from their respective publics when discussing how to press ahead with sensible and comprehensive institutional euro-area governance reforms. A consensus has yet to form. And one can only hope that it will have emerged by the time the next crisis hits.

What if there was a common European public sphere? It certainly cannot be expected – or desired – that we would find a narrowed-down debate which, for instance, might be all in favour of the ECB’s bond-buying programme. A vivid and controversial public debate can only be encouraged. After all, Europe is about democracy. The pros and cons of particular policies and proposals should be debated vigorously. Public figures and institutions should be scrutinised ruthlessly. But such a debate wouldn’t be one that focused primarily on each nation’s particular interests and circumstances. Instead, the well-being of the eurozone as a whole would serve as a common point of reference. In terms of our measure of “accumulated blame”, as shown in the graphs above, the patterns for all the four countries would look almost similar.

In such an environment, open public debate would help to set a common political agenda: what’s important, what’s problematic and what to do to improve the situation.

Our analysis suggests that such a pan-European agenda-setting process is still a distant prospect. In the meantime, analysing cross-country divergences in national discourses may serve as a useful if imperfect substitute.