The crowdfunding phenomenon

The concept of “crowdfunding” has increasingly drawn attention, most recently for its possible role in providing equity funding to start-ups. While th

See also the Finance Focus Breakfast "Crowdfunding: beyond the hype" taking place on May 16 at 8:30 am.

The concept of “crowdfunding” has increasingly drawn attention, most recently for its possible role in providing equity funding to start-ups. While there is a growing hype about crowdfunding, there are also many misperceptions. Crowdfunding initially started for philanthropic projects (in the form of donations) and then spread to consumer products (in the form of pre-funding orders) and lending. However, equity crowdfunding, sometimes called “crowdinvesting” is relatively new and currently comprises the smallest part of the crowdfunding market.

Crowdfunding can be defined as the collection of funds – usually made by means of a web platform – from a large pool of backers to fund an initiative. Two fundamental elements underpin the crowdfunding model and are both enabled by the development of the internet:

- By substantially decreasing the transaction costs, the web makes it possible to collect small sums from a large pool of funders, the “crowd”. The aggregation of many small contributions can result in considerable amounts of capital.

- The internet makes it possible to directly connect funders with those seeking funding, without the need of an active intermediary. Crowdfunding platforms assume the role of facilitators of the match however they differ in terms of the activities they perform. Some of them simply provide a portal and automatically post every project, while others screen and make a pre-selection of projects based on a set of criteria.

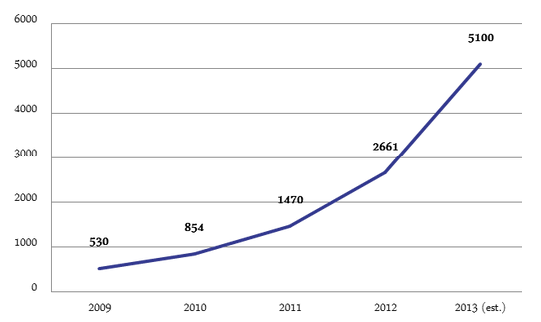

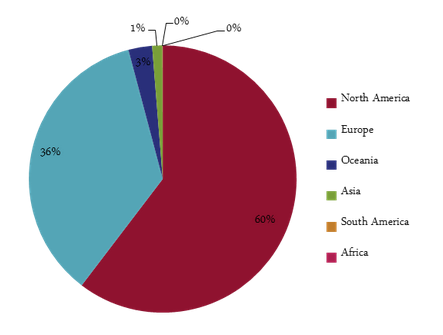

This relatively new financing model is experiencing exponential growth globally. In the period 2009-2013, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of the funding volumes was about 76% with an estimated total funding volume of $5.1bn in 2013. In terms of geography, the biggest market has been North America (and mostly the U.S. where the concept of crowdfunding started) with 60% of the market volume, followed by Europe, which has 36%.

A) Worldwide funding volumes ($M)

B) Geographical distribution (% of volumes, 2012)

Source: Bruegel elaboration on the basis of Crowdfunding industry reports 2012 and 2013 (Massolution).

While people tend to talk about crowdfunding in general, the crowdfunding phenomenon encompasses quite heterogeneous financing models. There are four main types:

- Donation-based model, in which funders donate to causes that they want to support with no expected compensation (i.e., philanthropic or sponsorship based incentive).

- Reward-based model, in which funders’ objective for funding is to gain a non-financial reward such as a token gift or a product, such as a first edition release.

- Lending-based model (crowd lending), in which funders receive fixed periodic income and expect repayment of the original principal investment.

- Equity-based model, in which funders receive compensation in the form of fundraiser’s equity-based revenue or profit-share arrangements.

The success behind the increasing popularity of crowdfunding is not only the access it provides to funding opportunities for broader populations, but also the mix of returns offered - social returns (donation and reward-based models), material returns (reward-based model) and financial returns (lending or equity-based models). Especially for donation and reward-based crowdfunding, people provide funding because they derive emotional and social benefits by contributing to the realization of a project.

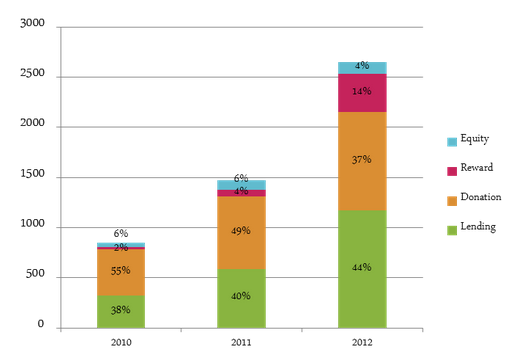

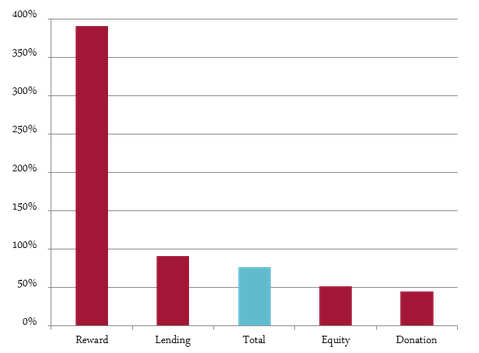

The figures below show the composition of the crowdfunding industry in the period 2010-2012. While in 2010 the industry was dominated by the donation-based model, in 2012 crowd lending was the largest category in terms of volumes, thus signalling that financial return motives were increasing in importance. However, the highest growth has been in reward-based crowdfunding, which grew by almost 400% CAGR between 2010 and 2012. Despite all of the “buzz” about equity crowdfunding, it is the smallest category of the overall industry and had a CAGR of about 50% during the period 2010-2012. The majority of that growth has been through European crowdfunding platforms.

A) Funding volumes by category ($M)

B) CAGR 2010-2012

Source: Bruegel elaboration on the basis of Crowdfunding industry reports 2012 and 2013 (Massolution).

Despite its small size, equity crowdfunding has received considerable attention in recent times, perhaps being confused with other forms of crowdfunding, particularly reward-based models. Proponents say that equity crowdfunding will allow businesses to raise capital faster and more efficiently. However, this would require changes in securities laws, specifically those related to issuing securities. Equity crowdfunding will essentially allow unsophisticated investors to invest directly in young risky companies with the expectation of a financial return.

Securities laws generally require an issuer to register to the national securities authority and to comply with strict reporting standards in order to get access to the general public. These requirements can be prohibitively expensive for small firms. Equity crowdfunding can reduce those costs and provide greater access to financing.

Currently, equity crowdfunding is only possible in some jurisdictions by exploiting exemptions, as defined in the national regulations of prospectus and registration requirements (Hornuf and Schwienbacher, 2014). Exemptions include the maximum amount that can be offered to the public, the maximum number of investors to whom the offer is made, the minimum contribution imposed on investors and whether the offer is made to “qualified” or “accredited” investors.

For example, in the European Union, firms do not need to comply with the prospectus requirement if the offer does not exceed €100,000 within a 12-month interval (Directive 2010/73/EU of 24 November 2010). However, national regulators can raise this threshold up to €5,000,000.

In the US, legislation did not have these exemptions, which meant it was not possible to raise capital through equity crowdfunding. But the situation changed on April 5, 2012 when President Obama signed into law the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act. Under this Act issuers can raise capital up to $1,000,000 within a 12-month period without registering with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or at the state level. Nevertheless, this new regulation has still not been put in place as the SEC has not implemented the specific rules yet. As a result of this delay, no equity crowdfunding deals have taken place in the US to date and existing crowdinvesting portals have adopted structures similar to angel-investing networks, in which only accredited investors can participate.

While the exemptions to existing securities legislation allow small firms to access the general public for financing, they also imply weaker protections for investors. Therefore, policy makers should be particularly careful in assessing the advantages and disadvantages of this new potential model of equity financing. There are currently many efforts underway in the European Commission as well as in national governments to assess the risks and opportunities of crowdfunding and identify the appropriate policies to put in place.

There are promising prospects for the various types of crowdfunding to provide new and much needed sources of finance to a variety of ventures. However, each model whether donation, reward, lending or equity-based, is driven by different underlying motivations and should not be used interchangeably in broader discussions of crowdfunding. While exponential growth is expected to continue, there are a number of challenges and potential pitfalls in the crowdfunding industry, particularly for equity crowdfunding. These aspects, as well as policy issues, will be discussed at the Bruegel event on 16 May and further analysed in an upcoming Bruegel publication.