Blogs review: The return of narrow banking

What’s at stake: Narrow banking has made a surprising comeback in the debate about the regulatory response to the crisis. While the idea has been

What’s at stake: Narrow banking has made a surprising comeback in the debate about the regulatory response to the crisis. While the idea has been around for a long time and was until recently dismissed as unrealistic, several specific versions of how this could be applied in the current environment have received support from a number of economists.

Dealing with run-prone liabilities

Stephen Cecchetti and Kevin Schoenholtz write that every financial crisis leads to a new call to restrict the activities of banks. One frequent response is to call for “narrow banks.” Paul Krugman writes that the basic idea that supporters for narrow banking share is that banks as we know them — institutions that issue promises to pay money on, or almost on, demand, while holding liquid assets that cover only a fraction of that potential demand — are inherently subject to runs, self-fulfilling losses of confidence. So they propose that we aim to eliminate such institutions; there would still be things we call banks, but they would simply be custodians of government-issued liquid assets.

John Cochrane writes that the central task for a regulatory response should be to eliminate runs. In the 2000 tech bust, people lost a lot of money, but there was no crisis. Why not? Because tech firms were funded by stock. When stock values fall you can't run to get your money out first, and you can't take a company to bankruptcy court. Runs are a pathology of specific contracts, such as deposits and overnight debt, issued by specific kinds of intermediaries. Among other features, run-prone contracts promise fixed values and first-come first-served payment. The central regulatory response to our crisis should therefore be to repair, where possible, run-prone contracts and to curtail severely those contracts that cannot be repaired.

The history of the Chicago plan

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi provide some history behind the idea of narrow banking. Irving Fisher was a strong supporter of the so-called Chicago Plan, which would implement 100% reserve banking. Here is a link to the one of the original documents from 1939. Another excellent read is from Ronnie Phillips entitled “The ‘Chicago Plan’ and New Deal Banking Reform.” He goes through the Chicago Plan and shows just how close it was to being implemented. The idea had a lot of support. Henry Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture handed the plan over the President Roosevelt in 1933 and wrote the following: “The memorandum from the Chicago economists which I gave you at [the] Cabinet meeting Tuesday, is really awfully good and I hope that you or [Treasury] Secretary Woodin will have the time and energy to study it. Of course the plan outlined is quite a complete break with our present banking history.”

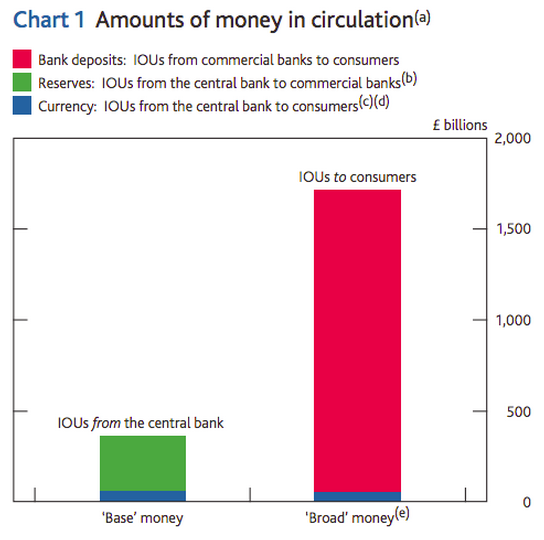

Source: Bank of England

Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof write that the Chicago Plan proposed:

- Separation of the monetary and credit functions of banking.

- Deposits/money must be backed 100% by public reserves.

- Credit cannot be financed by creation, ex nihilo, of bank deposits.

The Chicago plan revisited

Stephen Cecchetti and Kevin Schoenholtz write that all of these proposals, both the old and the new, have a common core: banks should be split into two parts, neither of which would supposedly be subject to runs. The first part is a narrow bank that provides deposits that are as safe as a central bank asset; the second operates like a mutual fund or investment company in which any risk of fluctuation in the value of the assets flows directly through to the ultimate investor. Frances Coppola writes the IMF’s paper “Chicago Plan Revisited” is a strict 100% reserve banking proposal, in which all deposits, irrespective of the risk appetite of the depositor, are backed by central bank reserves. The Kotlikoff plan envisages a disintermediated banking system in which banks “market” various types of funds but do not themselves do credit intermediation or maturity transformation.

John Cochrane writes that institutions that want to take deposits, borrow overnight, issue fixed-value money-market shares or any similar runnable contract must back those liabilities 100% by ST Treasuries or reserves at the Fed. Institutions that want to invest in risky or illiquid assets, like loans or MBS, have to fund those investments with equity and LT debt. Then they can invest as they please, as their problems cannot start a crisis.

John Cochrane argues that Pigouvian taxes provide a better structure for controlling debt than capital ratios or intensive discretionary supervision, as in stress tests. For each dollar of run-prone short-term debt issued, the bank or other intermediary must pay, say, five cents tax. Pigouvian taxes are more efficient than quantitative limits in addressing air pollution externalities, and that lesson applies to financial pollution. By taxing run-prone liabilities, those liabilities can continue to exist where and if they are truly economically important. Issuers will economize on them endogenously rather than play endless cat-and-mouse games with regulators.

Narrow banking is no panacea

Stephen Cecchetti and Kevin Schoenholtz write that narrow banking would not eliminate bank runs. The mutual funds of the narrow banking world would be subject to the same runs. Indeed, recent research highlights that – in the presence of small investors – relatively illiquid mutual funds are more likely to face exit in the event of past bad performance. Thus, in practice, illiquidity plays the same role in a world of mutual funds with many investors as it does in the classic Diamond-Dybvig model of a bank run. Since the mutual funds would be holding illiquid collective attempts at liquidation to meet withdrawal requests would lead to ruinous fire sales. After this happened even once, people would simply flock to the narrow banks, and there would be no source of lending. That is, a financial panic in a system with narrow banks would devastate the credit intermediation process.

Paul Krugman wonders if we’re really sure that banking problems are the whole story about what went wrong. Broader issues of excess leverage, and the resulting balance-sheet problems of many households appear key to understanding the slow recovery. And narrow banking would not have addressed that kind of leverage. Tyler Cowen also notes that traditional lender of last resort functions of central banks can deal with those dilemmas.