The coming productivity boom

AI and other digital technologies have been surprisingly slow to improve economic growth. But that could be about to change.

The last 15 years have been tough times for many Americans, but there are now encouraging signs of a turnaround.

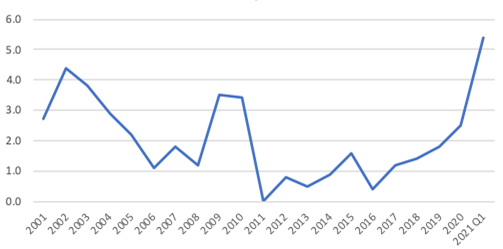

Productivity growth, a key driver for higher living standards, averaged only 1.3% since 2006, less than half the rate of the previous decade. But on June 3, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that US labour productivity increased by 5.4% in the first quarter of 2021. What’s better, there’s reason to believe that this is not just a blip, but rather a harbinger of better times ahead: a productivity surge that will match or surpass the boom times of the 1990s.

Annual Labour Productivity Growth, 2001 - 2021 Q1

For much of the past decade, productivity growth has been sluggish, but now there are signs it's picking up. (Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Our optimism is grounded in our research which indicates that most OECD countries are just passing the lowest point in a productivity J-curve. Driven by advances in digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, productivity growth is now headed up.

Technology alone is rarely enough to create significant benefits.

The productivity J-curve describes the historical pattern of initially slow productivity growth after a breakthrough technology is introduced, followed years later by a sharp take-off. Our research and that of others has found that technology alone is rarely enough to create significant benefits. Instead, technology investments must be combined with even larger investments in new business processes, skills, and other types of intangible capital before breakthroughs as diverse as the steam engine or computers ultimately boost productivity. For instance, after electricity was introduced to American factories, productivity was stagnant for more than two decades. It was only after managers reinvented their production lines using distributed machinery, a technique made possible by electricity, that productivity surged.

There are three reasons that this time around the productivity J-curve will be bigger and faster than in the past.

The first is technological: the past decade has delivered an astonishing cluster of technology breakthroughs. The most important ones are in AI: the development of machine learning algorithms combined with large decline in prices for data storage and improvements in computing power has allowed firms to address challenges from vision and speech to prediction and diagnosis. The fast-growing cloud computing market has made these innovations accessible to smaller firms.

Significant innovations have also happened in biomedical sciences and energy. In drug discovery and development, new technologies have allowed researchers to optimise the design of new drugs and predict the 3D structures of proteins. At the same time, breakthrough vaccine technology using messenger RNA has introduced a revolutionary approach that could lead to effective treatments for many other diseases. Moreover, major innovations have led to the steep decline in the price of solar energy and the sharp increase in its energy conversion efficiency rate with serious implications for the future of the energy sector as well as for the environment.

The costs of covid-19 have been tragic, but the pandemic has also compressed a decade’s worth of digital innovation in areas like remote work into less than a year. What's more, evidence suggests that even after the pandemic, a significant fraction of work will be done remotely, while a new class of high-skill service workers, the digital nomads, is emerging.

As a result, the biggest productivity impact of the pandemic will be realised in the longer-run. Even technology sceptics like Robert Gordon are more optimistic this time. The digitisation and reorganisation of work has brought us to a turning point in the productivity J-curve.

The third reason to be optimistic about productivity has to do with the aggressive fiscal and monetary policy being implemented in the US. The recent covid-19 relief package is likely to reduce the unemployment rate from 5.8% (in May 2021) to the historically low pre-covid levels in the neighbourhood of 4%. Running the economy hot with full employment can accelerate the arrival of the productivity boom. Low unemployment levels drive higher wages which means firms have more incentive to harvest the potential benefits of technology to further improve productivity.

When you put these three factors together—the bounty of technological advances, the compressed restructuring timetable due to COVID-19, and an economy finally running at full capacity—the ingredients are in place for a productivity boom. This will not only boost living standards directly, but also frees up resources for a more ambitious policy agenda.