The dollar surge

What’s at stake: The US dollar has gone through a very rapid appreciation over the past 6 months. While reduced form estimates are often presented to

What’s at stake: The US dollar has gone through a very rapid appreciation over the past 6 months. While reduced form estimates are often presented to argue that this will create a drag on the US economy, it is difficult to reason from a price change and the net effect could be positive if the price change is mostly driven by expansionary monetary policy abroad. In emerging economies, currency mismatches remain despite the recent increase in local currency sovereign debt and may create significant risks.

The dollar rally: then and now

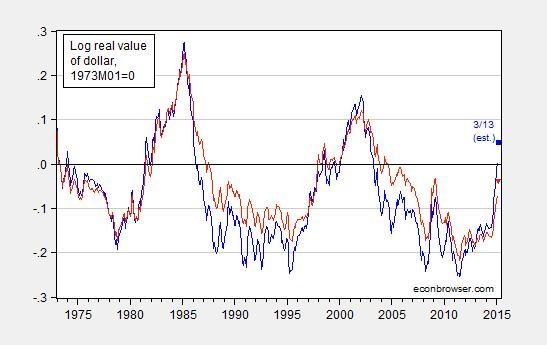

Matt O’Brien writes that the dollar is in the middle of its biggest rally in almost 40 years. As Citibank's Steve Englander points out, the dollar, going by its trade-weighted exchange rate, has increased more in percent terms the past 175 trading days than it has in any other similar period going back to 1976. Menzie Chinn writes that the figure below makes two points clear. First, the appreciation over the past six months is very rapid. Second, the appreciation is not unprecedented. The last such episode – during the post-Lehman flight to safety – was, however, short-lived. Before that, it was in the wake of the East Asian crises. Justin Fox writes that although the recent move against the euro is dramatic, but it has merely brought us back to about where we were when the euro came into being on Jan. 1, 1999.

Source: Econbrowser. Note: Log real value (CPI deflated) of US dollar against basket of major currencies (blue), and against broad basket (red), normalized to March 1973.

The impact on US growth: understanding the reasons for the price change

Scott Sumner writes that one should never reason from a price change. The effect of the dollar increase on the US economy depends the underlying factors. There are 4 primary reasons why the dollar might get stronger:

1. Tighter money in the US.

2. Stronger economic growth in the US.

3. Weaker growth overseas.

4. Easier money overseas.

For Sumner the major factor at work today is easier money overseas. That sort of policy shift in Europe is probably expansionary for the US.

Paul Krugman writes that Sumner is right that if the euro’s fall is being driven by expansionary monetary policy, this affects the U.S. through the demand channel as well as competitiveness, so it may be a wash. But I’ve already argued that the fall in the euro is much bigger than you can explain with monetary policy; it seems to reflect the perception that Europe is going to be depressed for the long term. And if that’s what drives the weak euro/strong dollar, it will hurt US growth.

Tim Duy writes that you can't reason from a price change, but reasoning in a general equilibrium framework is very, very hard. If ECB policy - and, by extension, the falling euro - was a net positive for the US economy, shouldn't we expect higher long US interest rates? But long US rates continue to hover around 2%, which seems crazy given the Fed's stated intention to start raising rates. Consider, however, that the stronger dollar does in fact represent tighter monetary conditions, but long interest rates are falling, which acts as a counterbalance by loosening financial conditions. Essentially, markets are anticipating that the stronger dollar saps US growth, but the Fed will respond with a slower pace of policy normalization, which acts in the opposite direction. So the stronger dollar does negatively impact growth, but market participants expect a monetary offset.

Liability mismatch and the original sin (of the corporate sector)

Jeffrey Frieden writes that the recent volatility of major currencies reminds us of the close relationship between exchange rate movements and international debt dynamics. While many still think of currency values as important primarily for their impact on the relative prices of domestic and foreign goods, today arguably the principal importance of currency values is their effect on the relative prices of assets and liabilities – including their potential to cause debt crises. In as much as domestic firms, or the national government, borrow in foreign currency, large depreciations can massively raise the real cost of foreign-currency liabilities. This was true in the gold-standard era, and the experience has been repeated again and again, from the developing-country debt crisis of early 1980s and Mexico’s “tequila crisis” of 1994, through the 1997-1998 East Asian financial crisis and after.

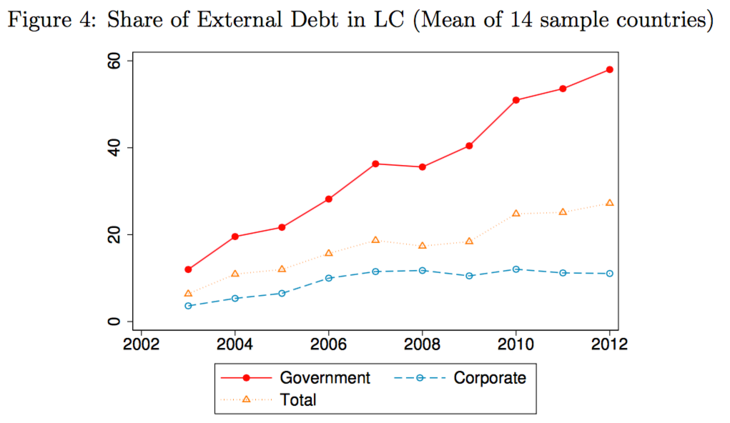

Jeffrey Frieden writes that liability mismatches persist, but are now mostly in the private sector. While emerging-market governments owe well more than a billion dollars to foreigners, most of it in local currency, emerging-market private corporations owe over two billion dollars to foreigners – and 90 percent of this is in foreign currency. Du and Schreger (2014) document that the share of LC sovereign debt in the external portfolio increased from 15 percent to 60 percent over the past decade. However, EM sovereigns are not issuing debt in their own currency in international markets. Instead, foreign investors are buying sovereign debt issued under domestic law. While the share of FC is shrinking dramatically for sovereign external liabilities, external emerging market corporate debt remains primarily in FC. The shares of LC in corporate debt and private external bank loans have increased at a much slower pace, reaching about 10 percent in 2012.

Source: Du and Schreger (2014). Note: LC = Local Currency.

Neil Irwin writes that the biggest difference this time around compared to the Asian crisis of the late 1990s and the Argentine crisis of 2002 is is that private companies, not governments, have incurred debt in a currency not their own. Paul Krugman disagrees. This time is not different: the Asian and Argentine crises were also about private-sector debt, with Asian public debt, in particular, quite low before the crisis hit. This point matters because of the temptation to fiscalize crisis narratives – the urge to see everything that goes wrong as the result of budget deficits (there’s already been a huge effort to retroactively fiscalize the euro crisis, and we need to push back against attempts to do the same to Asia).