Blogs review: The global dimension of tapering

What’s at stake: Emerging markets have had a tough summer, as central banks of advanced economies have made clear that the normalization of monet

What’s at stake: Emerging markets have had a tough summer, as central banks of advanced economies have made clear that the normalization of monetary policy was underway. Although this development has generated a renewed interest in the international transmission of monetary policy and was a central part of the discussion at Jackson Hole, it remains unclear whether this sudden reversal in capital flows will remain mostly benign or will deteriorate into a full-fledged emerging market crisis.

The unintended consequences of QE

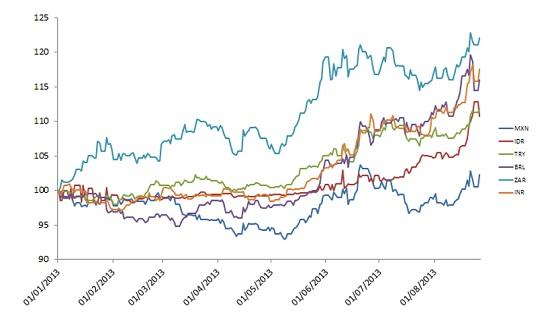

John Plender notes that since the great QE tapering debate began in May, external capital addicts such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa have been badly hit by a reversal of the flow. Marco Annunziata writes many emerging markets have had a rough summer. South Africa suffered a deeper depreciation than India year-to-date, as did Brazil before its central bank stepped in announcing a new foreign exchange intervention program.

Source: Marco Annunziata

Paul Krugman writes that the big question is how serious this markets’ sudden turn against emerging economies really is — is it the kind of thing that costs a few finance ministers their jobs and maybe causes mild recessions when central banks hike rates, or is it a potential economic catastrophe? His take is still that the risks of real disaster are low because these countries have a much lower level of external debt that they used to, and are thus less subject to the infamous devaluation/balance sheet effect. Now it’s possible that I and everyone else who tried to understand what happened in the 90s have the wrong model. But given what we know, I’m relatively though not totally calm.

Then and Now: 1994 vs. 2013

Guillermo Ortiz writes that as in past episodes of Fed tightening, emerging markets are at the center of the turmoil. But this time the adjustments taking place are the product of imbalances that originated in the developed world.

The Institute of International Finance (HT Laura Tyson) compares the current exit strategy with those of 1994 and 2004. After the 1990-91 crisis, the Fed’s first rate hike came in February 1994 and was largely unanticipated by markets. Over a course of twelve months, the Fed increased its policy rate from 3% to 6%. During the same period, the yields on 10yr Treasury bonds rose by around 200 basis points. The sharp and sudden rise in bond yields had significant international spillover effects on global financial markets. Sovereign bond yields increased in many developed and emerging market economies. The Fed’s 2004 exit was largely anticipated. During the 2004-2006 period, the Fed increased its policy rate gradually from 1% to 5.25% by following a preannounced schedule of actions. Although this slow exit strategy enabled the Fed to avoid a bond-market crash (the increase in long-term rates was small while short-term rates increased sharply) and had a limited initial impact on global markets compared with the 1994-95 cycle, it contributed to financial excesses in the U.S. economy (i.e., credit and asset bubbles).

Source: The Institute of International Finance

Dilemma not trilemma

Helene Rey writes in her Jackson Hole paper that the global financial cycle has transformed the well-known trilemma – in a financially integrated world, fixed exchange rates export the monetary policy of the center country to the periphery – into a ‘dilemma’: Independent monetary policies are possible if and only if the capital account is managed directly or indirectly via macroprudential policies. Based on a recursive VAR, Rey suggests that one important determinant of the global financial cycle is monetary policy in the center country, which affects leverage of global banks, credit flows and credit growth in the international financial system. Cross‐border flows and leverage of global institutions transmit monetary conditions globally, even under floating exchange‐rate regimes. Fluctuating exchange rates cannot insulate economies from the global financial cycle, when capital is mobile.

Jean-Pierre Landau writes that the idea that liquidity "spills over" is so spontaneously intuitive that it proves hard to resist. That naïve vision conveys some truth. Liquidity moves around the world through banking and portfolio channels. The dynamics, however, are very complex and "the popular image of a cascade of liquidity pouring out of the United States can be highly misleading" (Caruana, 2012b). Capital markets are by no mean homogenous and frictionless. There are holes, amplification mechanisms and feedback loops, all of which determine how liquidity is created, how it circulates and what impact it may have.

Terrence Checki of the FRBNY writes that the reality is that financial flows and cross-border linkages have reached a scale such that all economies have become much smaller in relation to global market dynamics. This is a real problem, one that confronts policy makers around the world with challenges that don’t admit easy solutions. Indeed, it has even been an issue for the US at times, such as when crowding into our bond market helped hold down the long end of our yield curve even as we were tightening.

Jean-Pierre Landau writes that although portfolio flows remain relatively modest, these flows represent the marginal investor, the one that instantly determines the market equilibrium and its price, with huge impact in times of stress when market liquidity dries up. Portfolio flows have become more volatile, with higher frequency and shorter cycles as compared with banking flows. With risky assets in emerging markets becoming more substitutable with those in advanced economies, it has amplified the spillover from monetary policy in advanced countries.

The options for emerging markets

Cardiff Garcia writes that the chart by Citi makes an important point and is self-explanatory, but it isn’t comprehensive. Notably excluded is the imposition of capital controls on outflows, which thus far have been mostly resisted with the exception of some limited measures in India. They too are a bad option as controls on outflows rarely work. Or perhaps it’s more correct to say that there is an awful lot of disagreement about the prior instances in which they were tried and might have worked. This doesn’t mean that controls can’t work in India or elsewhere. But in addition to their historical impotence, such controls also carry the risk of further scaring off investors at precisely the time when they seek reassurance.

Source: Citi Research (HT FT Alphaville)

Brad DeLong writes that with increasing signs the North Atlantic central banks will tighten over the next several years, forward-looking financial markets are incorporating that tightening into their pricing of emerging-market assets today. DeLong writes that the best option is for them to raise interest rates enough but no more so that the decline in the currency value is small enough that the boost in exports neatly offsets the decline in domestic interest-sensitive spending and the economy becomes not too cold or too hot but just right. Why isn't this option a no-brainer? The fear appears to be the expectations of future nominal currency values vis-à-vis the dollar are not well-anchored. Thus letting the rupee drop now does not restore confidence by making foreign exchange speculators expect the next bounce of the rupee will be upward in value. Rather, it destroys confidence by leading them to expect the unleashing of a domestic exchange-rate inflationary spiral.