Blogs review: The 2008 FOMC transcripts

What’s at stake: Fed watchers have spent the past week dissecting the much-awaited 1865 pages of transcripts covering the 2008 meetings

What’s at stake: Fed watchers have spent the past week dissecting the much-awaited 1865 pages of transcripts covering the 2008 meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The transcripts provide a detailed account of the Fed’s decisions during the most turbulent times of the Great Recession. In the blogosphere, the discussion has focused on the extent to Committee obsessed with the wrong crisis and the performance of key personalities.

The inflation threat in the Lehman years

Paul Krugman writes that what’s striking about the Federal Reserve transcripts of 2008 is the extent to which they were obsessed with the wrong thing. Historians of the Great Depression have long marvelled at the folly of policy discussion at the time. For example, the Bank of England, faced with a devastating deflationary spiral, kept obsessing over the imagined threat of inflation. But it turns out that modern monetary officials facing financial crisis were just as obsessed with the wrong thing as their predecessors three generations before.

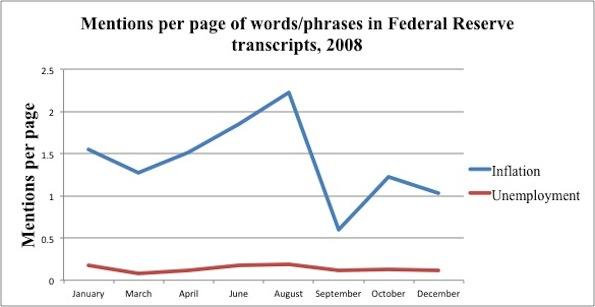

Matthew O’Brien has done the math on the transcripts. At the June 2008 meeting, there were 468 mentions of inflation, 44 of unemployment, and 35 of systemic risks/crises. At the August 2008 meeting, there were 322 mentions of inflation, 28 of unemployment, and 19 of systemic risks/crises. At the September 16 2008 meeting (that is a day after Lehman failed) there were 129 mentions of inflation, 26 of unemployment, and only 4 of systemic risks/crises.

Source: Free Exchange

Matthew O’Brien reports that even the day after Lehman, the Fed wasn't sure whether inflation or the financial crisis was the bigger risk to the economy. In that meeting the hawks were monomaniacally focused on headline inflation that hadn't yet fallen all the way from its summer peak. Even though commodity prices and inflation expectations were both falling fast, Hoenig wanted the Fed to "look beyond the immediate crisis," and recognize that "we also have an inflation issue." Bullard thought that "an inflation problem is brewing." Plosser was heartened by falling commodity prices, but said, "I remain concerned about the inflation outlook going forward," because "I do not see the ongoing slowdown in economic activity is entirely demand driven." But it wasn't just the hawks who wanted to leave rates unchanged. It was everybody at the Fed, except for Rosengren.

The pitfalls of consensus building

Jon Hilsenrath writes that the story on Chairman Ben Bernanke has been written many times: He was slow to respond to the grave situation in financial markets in 2007 and 2008, but moved with command and authority to steer the economy straight once he recognized what was at stake.

Brad DeLong wonders if we wouldn’t have had a better monetary policy under a less collegial and consensus oriented Bernanke. In the past, the views of the other members – with their varying backgrounds in banking, regulation, and elsewhere – were of little or no concern. But former Chairman Ben Bernanke’s FOMC was different. It was collegial, respectful, and consensus-oriented. As a result, there was a deep disconnect between Bernanke’s policy views, which followed from his analyses in the 1980’s and 1990’s of the Great Depression and Japan’s “lost decades,” and the FOMC’s failure in 2008 to sense what was coming and to guard against the major downside risks.

Chris House writes that it’s virtually impossible for economists today to look back and give a fair assessment of the Fed’s interpretation of the data at the time. We have the burden of hindsight and the luxury of being able to casually contemplate possible courses of action – neither of which were available to the Fed in 2008.

The missing BOE and ECB transcripts

Tony Yates writes that there are no transcripts in the UK [Danny Blanchflower corrects Yates and says that there were transcripts recorded of UK MPC meetings, but they are not released]. The MPC discussion is recorded pretty much verbatim by a small cadre of talented minute takers. And then there are subsequent meetings of MPC with the minute takers to determine what it is they want to have recorded about the meeting. The document describes itself as ‘Minutes’, but that term’s definition does not promise a verbatim report of the discussion, and the document does not deliver one.

Real Time Economics writes that the ECB keeps its deliberations under wraps for 30 years. This means under current rules that the public has to wait until about 2028 before the internal deliberations of its policy makers are made known. Even then, it’s far from certain that the detail published will be as thorough as what the Fed provides. Thirty-year old documents of bodies that preceded the ECB are written as indirect citations. Statements are summarized, but without direct quotes. They don’t read like a film script in the way the Fed transcripts can.

Tony Yates writes that there are considerable advantages to having a distillation of the discussion UK-style released promptly. It clearly helps the MPC manage the message it wants markets to take from the meeting, and give the appropriate context to the decision. The ‘what do we want them to think we said?’ model of minute-taking serves as a policy statement accompanying (with a small lag) the decision itself. But not having transcripts prevents us from judging ex-post the quality of monetary policymakers.

The stance of monetary policy

Historinhas reports the farewell remarks of Frederic Mishkin at the August meeting. Among the concerns he had for the FOMC going forward was the real danger of focusing too much on the federal funds rate as reflecting the stance of monetary policy. Many deep mistakes that have been made in monetary policy because of exactly that focus on the short-term interest rate as indicating the stance of monetary policy. In particular, when you think about the stance of monetary policy, you should look at all asset prices, which means look at all interest rates. All asset prices have a very important effect on aggregate demand. Also you should look at credit market conditions because some things are actually not reflected in market prices but are still very important.