Blogs review: The emerging market turmoil

What’s at stake: Last week was a volatile week in financial markets, with many emerging markets assets experiencing a strong correction. As emerg

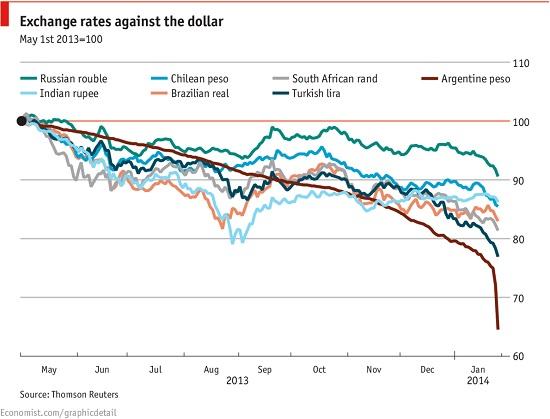

What’s at stake: Last week was a volatile week in financial markets, with many emerging markets assets experiencing a strong correction. As emerging countries’ central banks respond with sharp interest rate hikes to defend their currencies, many commentators wonder whether and how different this sudden stop will be from previous ones.

The merging market selloff

Nouriel Roubini writes that the financial turmoil that hit emerging-market economies last spring, following the US Federal Reserve’s “taper tantrum” over its quantitative-easing policy, has returned with a vengeance. This time, the trigger was a confluence of several events: a currency crisis in Argentina, where the authorities stopped intervening in the forex markets to prevent the loss of foreign reserves; weaker economic data from China; and persistent political uncertainty and unrest in Turkey, Ukraine, and Thailand.

Source: Graphic Detail blog

Nouriel Roubini writes that the list of emerging countries in trouble include India, Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey, and South Africa – dubbed the “Fragile Five,” because all have twin fiscal and current-account deficits, falling growth rates, above-target inflation, as well as political uncertainty from upcoming legislative and/or presidential elections this year. But five other significant countries – Argentina, Venezuela, Ukraine, Hungary, and Thailand – are also vulnerable. Political and/or electoral risk can be found in all of them, loose fiscal policy in many of them, and rising external imbalances and sovereign risk in some of them.

The re-run of a well-known movie

ObservingGreece writes that the current outflow of capital from emerging markets feels like the re-run of a movie seen a long time ago. Today's story is virtually the same as it was then. First, something happens which conveys to foreign capital the confidence that risks are low and returns are high. Next step: an avalanche of foreign capital hits the emerging market. Next step: incomes and asset prices in the emerging market go up. Next step: much of the increased wealth is spent on consumption of imported goods instead of investment, driving the current account balance into dangerous, negative levels. Next step: something happens which makes foreign capital doubt that risks are still low and returns still high. Final step: foreign capital is withdrawn.

Paul Krugman writes that although the outline of the story remains the same (Latin America in 1982, Asia in the 1990s, peripheral Europe in the past few years), the intervals between these crises are getting shorter and the effects keep getting worse. Real output fell 4 percent during Mexico’s crisis of 1981-83; it fell 14 percent in Indonesia from 1997 to 1998; it has fallen more than 23 percent in Greece.

The return of macroeconomic populism

Paul Krugman writes that we’re seeing a mini-revival of what Rudi Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards long ago called macroeconomic populism (“an approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income distribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies”). This involves making the symmetrical error to that of people who think that running deficits and printing money always turns you into Zimbabwe; it’s the belief that the orthodox rules never apply. And it’s an equally severe mistake.

Dani Rodrik and Arvind Subramanian write that emerging markets aren’t hapless and undeserved victims; for the most part they are simply reaping what they sowed. Many large emerging-market countries have consciously and enthusiastically embraced financial globalization. Having chosen to embrace financial globalization, emerging market countries then proceeded to follow economic policies that were bound to create volatility. The fact is that the emerging economies’ troubles are domestically generated problems and not the fault of foreigners. The complaint of emerging-market countries seems a classic case of blaming outsiders for choices and actions that have been predominantly domestic.

Mark Dow writes that people will overstate how bad fundamentals are as price action worsens. But many things, fundamentally, are different (better) this time. Gone is the fixed FX regime and the original sin. Domestic EM financial markets are deeper. Reserves are higher.

Assessing the global impact of a new emerging market crisis

Wolfgang Munchau writes that as always the US is relatively robust to global shocks, up to a point – not so Europe, least of all the eurozone. Start with the direct effect of the Turkish crisis on Greece and Cyprus. The magnitude is not that great on a global scale, but significant for the two countries. Their main industry – tourism – is competing head-on with Turkey. The Greeks and Cypriots have gone through incredible pains to improve their competitive position through wage and price cuts. The recovery in tourism is one of the few bright spots in their still depressed economies. The devaluation of the Turkish lira has put paid to all of this. Any holiday-maker headed for the eastern Mediterranean will find Turkey a lot cheaper. It is a game Greece and Cyprus cannot win.

Wolfgang Munchau writes that for the eurozone as a whole, the main problem is not trade because it has a moderately large trade surplus. Instead, the problem is the impact on the price level. At 0.8 per cent we are not far from outright deflation. A single large shock may be all that is needed. What is happening in Turkey and Argentina may constitute such a shock.