Blogs review: Dealing with an impaired monetary transmission mechanism

What's at stake: Dealing with the fragmentation of capital markets along national borders and the resulting lack of funding for SMEs in the countries

What’s at stake: Dealing with the fragmentation of capital markets along national borders and the resulting lack of funding for SMEs in the countries of the periphery has been a central issue for the ECB for some time already. But the prospect of a prolonged double-dip has rendered it even more urgent. In this review, I document the extent to which the transmission mechanism of monetary policy within the eurozone is broken and discuss several proposals – such as a negative lending deposit rate and the creation of a new program targeted to SMEs – designed to increase the flow of credit in the periphery.

The broken mechanism

The Economist writes that when the ECB lowered its rate by half a percentage point in 2003, firms’ borrowing rates fell by the same amount. When it tightened policy between 2005 and 2007, the pattern was the same. As the ECB rate went from 2% to 4%, firms’ borrowing rates rose from 4% to 6%. This predictable wedge between policy and market interest rates meant the ECB knew how its decisions would feed through to the interest rates that influence output and inflation. In 2008, as the euro zone started to contract, the ECB slashed its main rate from 4.25% to 1%. But firms’ borrowing rates fell by less than normal.

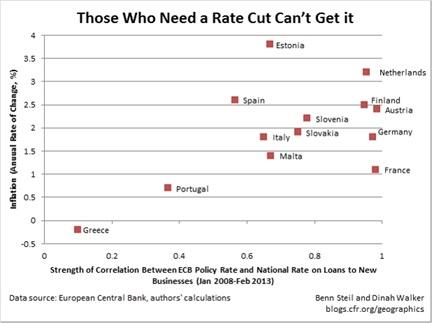

Brad Plummer writes that ECB interest-rate cuts have had little effect over the past five years on two of the countries that really need economic stimulus — Greece and Portugal — in part because their banking systems are in tatters. This “transmission mechanism” isn’t quite as broken for Spain and Italy, but even those two struggling countries get less of an economic boost from rate cuts than their neighbors up north.

Place du Luxembourg writes that the decline in M3 and EONIA volumes hide a wide divergence between the core and the periphery, caused by core banks considerably decreasing their exposure to the periphery. It meant that peripheral banks were largely unable to fund in the interbank market from their core competitors, who preferred to stash their cash at the ECB. Gregory Connor writes that the bank lending market dislocation in the Eurozone is arguably more severe than the CMO, CMO-CDS, CP market dislocation which sparked the 2007-8 credit-liquidity crisis.

Michael McMahon writes that this broken transmission mechanism is of particular concern given the importance of SMEs to the euro area economy (especially for jobs—SMEs account for about 75% of total euro area employment) and given the reliance of SMEs on bank lending for both investment but also, perhaps more pertinently, for working capital purposes. The ECB already has schemes, such as long-term refinancing operations (LTRO) that offer lower funding to banks. In fact, the ECB already allows banks to finance SME loans via the normal ECB operations at the refinancing rate. The problem is that there are large haircuts applied to the collateral; even if it is an Asset-Backed Security of SME loans, the haircut is 16%.

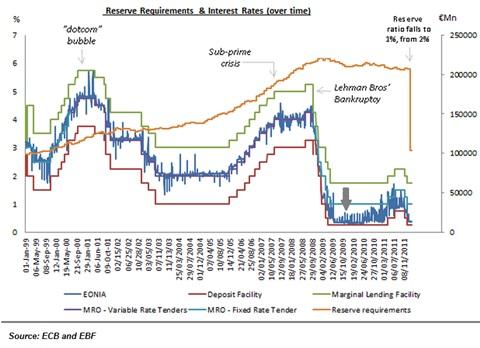

A negative interest rate on deposit

Place du Luxembourg writes that traditionally speaking the MRO is the interbanking target of the ECB, which means that a rate cut of the MRO is meant to make funds cheaper as measured by EONIA, but also EURIBOR, EUREPO and EURO-SWAP. However, since 2009 and the change from a variable rate/pro rata allotment to a fixed rate/full allotment of MRO funds at auction, the Deposit Facility has been the benchmark of the interbank market. As a result, cutting the MRO serves no purpose.

Source: Place du Luxembourg

Megan Greene writes that in its efforts to get banks lending again, the ECB is looking at excess reserves – some 120 billion euros the banks have been holding on deposit at the central bank for safekeeping. If the ECB were to introduce a negative interest rate on deposits, effectively charging a fee, the banks might choose to lend the money out rather than watch it lose value. This logic is far from ironclad. Instead of lending the money to businesses and individuals, the banks could simply park it elsewhere – for example, in the sovereign bonds of Germany and other countries perceived to be financially healthy. This might benefit Germany by further pushing down its borrowing costs, but would do little to unblock credit to businesses. Banks might even try to cover their losses on the ECB deposits by charging higher interest rates on business loans, precisely the opposite of the desired outcome.

Scott Sumner writes that Greene is right that the initial effect of negative IOR would be for banks to buy government bonds. This means that banks would essentially be doing “QE.” Why is that better than the ECB doing QE? It’s not clear it is, although some people worry about the bloated balance sheets of the major central banks, and negative IOR would greatly reduce that “problem.”

Megan Greene argues that there are better ways for the ECB to encourage banks to lend. Banks might make more business loans, for example, if the ECB made it easier to use those loans as collateral for cheap central-bank credit. The ECB could do so by loosening requirements for the amount and type of business loans that it accepts in exchange for liquidity, and by lending more against a given value of loans. The central bank could go a step further and agree to purchase business loans in the secondary markets. Banks would be more willing to accept the risk of lending to small and medium-sized enterprises if they knew they could turn around and sell those loans to the ECB. For now, the ECB is unwilling to accept this degree of risk on its own balance sheet. That could change as the recession in the euro area deepens further.

The UK's Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS)

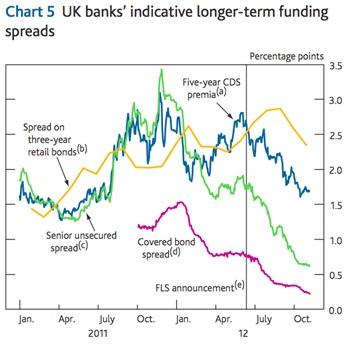

The Economist writes that Britain’s experience provides ideas the ECB can use. The Bank of England’s policy rate has been 0.5% since 2009, yet SME borrowing costs have been high and business lending has contracted. Since studies showed that tight loan supply was partly to blame, a new tool, the Funding for Lending scheme (FLS), was created in 2012. Banks first swap their assets, including bundles of SME loans, with the central bank. In return they get ultra-safe treasury bills. Banks can then offer this good collateral as security when they borrow. Because the bank’s creditor gets the safe assets if the bank defaults, this form of funding is cheap.

Michael McMahon writes that under the FLS all banks can get funding worth five per cent of their existing stock of loans at a funding cost of 25bps. Regardless of what the bank does with net new lending (lending net of repayments), the bank can get access to this five per cent; however, for every £1 of new net lending, they can access £1 more of FLS funding at 25bps. If they cut net new lending, they can still access the five per cent stock of funding, but the price on all the funding gradually rises up to a maximum of 150bps; this prevents deleveraging banks from taking the funding and using it to not expand lending. While the scheme in its first incarnation was successful at lowering banks funding costs, the concern was that banks were only expanding lending to safe borrowers (large corporates or high LTV mortgage borrowers). Therefore the UK authorities recently extended the original FLS and altered the incentive such that SME lending is worth ten times that of other types of new lending in terms of eligibility for new FLS funding; £1 of new net lending to SMEs would allow banks access to £10 of extra funding at 25bps.

Source: Bank of England

Implementation issues for a new program targeted to SMEs

Gavyn Davies writes that to make a difference, the new ECB program for SMEs needs to involve not just a liquidity provision, but a genuine risk transfer from banks or the EIB (which would package the loans) to the ECB itself. It also needs to be done in tens of billions of euros, which might take a while. The logistics of getting this done are not straightforward.

Michael McMahon lists a number of challenges for the ECB if it were to design a similar scheme:

- Will the ECB operate the scheme through any existing schemes, for example adjusting the haircut applied to SME loans in refinancing operations, or will it design a specific scheme to meet the challenge?

- How can the design of the scheme in order to ensure that SMEs facing the greatest credit restrictions see the greatest expansion of credit? Perhaps the scheme will involve some form of dependence on the state of the national macroeconomy? Or the relative contraction of SME lending compared to some previous norm? Perhaps it is possible to link available funding to those economies in which equivalently measured SME loan applications are turned down more frequently?

- Can the ECB, the national central banks and the supervisory authorities get access to sufficiently detailed data to proceed with such an approach? Can policy incentivize cross-border SME lending in weaker economies by banks in stronger economies?

In a recent email, Nivethan Tharmendiran wrote that a SME facility could take several forms.

- A supra national backed Bank Collaterized Loan Obligation (CLO)'s using SME pools or less likely supra-national issued CLOs both of which would be ECB eligible.

- A more broad-stroked approach could see an LTRO that uses SME collateral - UK FLS style.