Weathering the storm: differences in crisis response in the EU and Korea

There is a striking difference between the ways in which the EU and Korea responded to the crisis. While the initial shock was broadly similar after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, Korea has recovered very quickly and output in 2011Q3 exceeded by almost 10 percent the pre-crisis level, but the EU’s output has not yet returned to pre-crisis values. What could explain this difference?

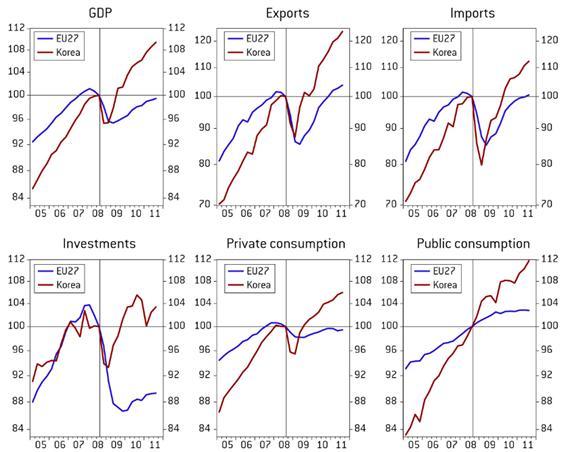

Figure 1 shows quarterly developments in GDP and its main components in the EU27 and Korea. There are indeed striking differences. In the EU, the decline in GDP started a few quarters before the collapse of Lehman Brother and the fall accelerated up to 2009Q1, while in Korea there was a sudden drop in a single quarter, in 2008Q4. But the major difference is the aftermath: in Korea growth picked up instantly when global trade started to recover, while the EU recovery was gradual and modest, even if there are differences between EU countries. Certainly Korea, a country that has a lower GDP per capita than the EU27 average, should grow faster because of convergence, but the differences are unlikely to be related to this convergence factor.

Major differences can also be observed in domestic demand developments. The reaction of investors was almost identical up to 2009Q1, but investment fell further in the EU and has hardly recovered, in contrast to Korea where it has recovered quickly. Initially, private consumption fell much more in Korea than in the EU, but while it has also recovered quickly in Korea, it remained sluggish in the EU. Public consumption grew much faster in Korea. The external trade dynamics were not that different, though growth, especially of exports, was much faster in Korea.

One factor that could explain these differences is policy response. Korea has implemented a very significant fiscal stimulus: the fourth largest among G20 countries, well above the stimulus provided by any EU countries. While most EU countries also embarked on fiscal stimulus in the early phase of the crisis, their stimulus packages were much smaller due to much more binding fiscal constraints, which is the consequence of the generally higher debt levels and contingent liabilities. Also, several EU countries had to consolidate later. The Korean case therefore exemplifies the benefits of low public debt and the consequent fiscal space.

The differences in monetary policy response were not significant. Both the European Central Bank and the Bank of Korea lowered interest rates considerably and implemented decisive measures to support the banking sector. Both central banks cooperated with the Federal Reserve in terms of swap agreements to alleviate the US dollar liquidity problems of their respective financial systems.

However, there was a major difference in the reaction of the exchange rate: the real effective exchange rate of the Korean won depreciated by more than 30 percent and is still about 20 percent below its pre-crisis value. A recent International Monetary Fund research study concluded that without this significant depreciation, the output contraction would have been about five percent greater. In contrast the euro, the currency of 17 EU countries to which three others maintain a fixed exchange rate, after a sharp but short-lived impact, hardly depreciated during 2008-09. There was depreciation in 2010 but to limited extent, only about 10 percent, and, according to measures of the equilibrium exchange rate, the euro continues to be overvalued. This is certainly not helpful for economic recovery. On the other hand, most central European EU countries with floating exchange rates, as well as Sweden and the UK, witnessed a significant deprecation, which may have helped to dampen the impact of the crisis.

A major, and perhaps the most important, reason for the different outcomes in the EU and Korea could be related to the lingering euro crisis, which impacts all EU countries because of their strong trade and financial linkages. The crisis has revealed specific problems related to (a) public finance sustainability and resolution of sovereign debt crises, (b) excessive private sector imbalances and competitiveness problems, and the consequent private sector debt accumulation, (c) the lack of sufficient mechanisms for fostering structural adjustment, (d) the lack of EU-wide mechanisms for supporting economic growth in the most distressed regions, (e) the discrepancy between the high-level banking sector integration and the weaknesses of the EU frameworks for regulation, supervision, and crisis resolution, and (f) more generally the weaknesses in the governance of the euro area, which has led to patchy, inadequate and belated policy responses.

There is a negative feedback loop between the crisis and growth in the EU, and without effective solutions to overturn the crisis, growth is unlikely to resume.

Figure 1: Quarterly GDP and its main components (2008Q3 = 100, constant prices, seasonally adjusted), 2005Q1-2011Q3

Source: Eurostat and OECD.