European Union grain imports from Ukraine: the right decision and a cynical rebellion

The European Commission was right to let restrictive measures on Ukrainian grain lapse, but the decision has had negative side-effects.

On 15 September, the European Commission allowed a temporary ban on Ukrainian grain imports (maize, wheat, rapeseed and sunflower seed) to expire. The ban had been introduced on 2 May 2023 under pressure from five EU countries bordering Ukraine (Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia), which feared their own producers would be harmed. Initially set for one month until 5 June, the ban was subsequently extended.

It is unclear what impact the end of the ban will have as Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have also introduced unilateral bans. Nevertheless, ending the EU-level import restrictions (which applied only in the five countries) was the right decision for several reasons.

First, Ukraine, which has been fighting Russian aggression for more than a year and a half, deserves exceptional support from the EU, also in the economic and trade spheres. Grain is one of Ukraine’s most critical exports. Russia has largely blocked the maritime export route since it withdrew, on 17 July 2023, from the United Nations sponsored Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI). Thus, facilitating exports to the EU, and via the EU to third countries, provides a respite for Ukrainian agriculture producers and the country’s balance of payments.

Second, the temporary ban introduced in May was problematic from the point of view of the integrity of the European single market and the EU’s common trade policy. In the long run, it was ineffective because grain imports from Ukraine could enter the ‘bordering’ countries via other member states within the EU customs union and common market.

Third, it was good that the Commission did not give in to the aggressive pressure from some EU countries, which demanded an extension of the ban until the end of 2023. The Commission’s decisions should be determined by the EU Treaties and EU strategic interests in the long run, rather than attempts to please various lobbies in individual countries and to meet their short-term political needs.

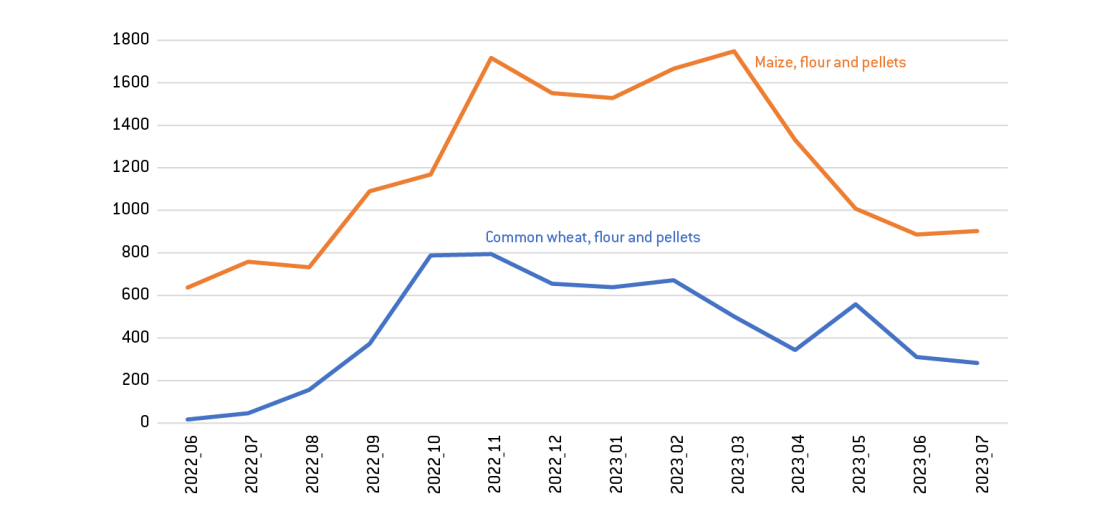

Fourth, advocates of the extension used disputable economic arguments. In particular, there is little evidence in the available statistics for the supposed massive influx of Ukrainian grain to the EU. Volumes of the two main grain import items (wheat and maize) were declining from their peaks in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023 already before the introduction of the temporary ban (Figure 1).

Figure 1: EU imports from Ukraine of selected grains, thousand tonnes, June 2022-July 2023

Source: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/#

In the 12 months from August 2022 to July 2023, total EU imports from Ukraine amounted to the equivalent of 4.6% of EU average wheat production and 22.2% of average maize production in 2018-2022. However, EU maize production in this period decreased by more than 20 million tonnes compared to 2021 because of a bad harvest. The imports from Ukraine only compensated partly for this gap. Meanwhile, the EU increased its grain exports to African countries, so global grain export flows were just rerouted.

Fifth, the Commission’s decision is good for stabilising global food markets and keeping global food prices affordable, especially in the context of the expiry of the BSGI. This is a critical issue for food security in developing economies, particularly in Africa and the Middle East.

However, the Commission’s decision also has drawbacks.

As a condition for not extending the EU import ban, Ukraine was forced by the Commission to introduce export control measures “…to prevent any market distortions in the neighbouring Member States”. What is meant by “any market distortions” remains unclear and may be a subject of arbitrary interpretation. Incidentally, distortions can be caused by internal policies and institutional solutions in EU countries, rather than imports from Ukraine.

The Commission’s press release suggests export licensing as an instrument of export control in Ukraine. This is not a good policy tool, especially in Ukraine’s imperfect institutional environment where it may encourage corruption.

Most likely, this was an attempt by the Commission to reach a compromise with the five bordering EU countries. Unfortunately, this attempt failed. The continuing unilateral import bans in Hungary, Poland and Slovakia also extend the restricted food product list. Ongoing election campaigns in Poland and Slovakia do not help in making rational policy decisions.

The unilateral bans are grave policy mistakes. First, they are an open infringement of the EU Treaties, according to which trade policy is the exclusive competence of the EU governing bodies. Second, they undermine the EU policies on Ukraine. Third, they partly undermine the impressive records of the three rebelling countries (and their societies) in supporting Ukraine. They bring into question their solidarity with the struggling nation and their sincerity in endorsing Ukraine’s EU membership aspiration.

Ukraine has filed lawsuits against the three countries at the World Trade Organisation, and is considering introducing retaliatory import bans. In response, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have withdrawn from the Coordination Platform, which monitors Ukrainian grain exports. Poland’s prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki threatens to introduce additional trade sanctions against Ukraine. Such a scenario can only please the Kremlin.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Rebecca Christie, Zsolt Darvas, Maria Demertzis, Heather Grabbe, Luca Moffat, Lucio Pench and Armin Steinbach for their comments and suggestions.