The structural budget balance limbo

A key indicator in the EU’s fiscal framework is the structural budget balance, but estimates of the indicator by the European Commission, IMF and OECD

Recently, the finance ministers of eight euro-area countries expressed doubts about EU methods for estimating the cyclical position of the economy (the so-called ‘output gap’). They worry about its implication for EU fiscal rules.

In my view, the concerns of these ministers are justified. In this post I illustrate the uncertainty in estimations of the so-called structural budget balance, which is a key fiscal indicator in the EU’s fiscal framework. I compare the estimates of the European Commission, IMF and OECD.

The structural balance of the government, an unobserved variable, aims to measure the ‘underlying’ position of the budget by excluding the impacts of temporary effects: the economic cycle and one-off measures.

In a recession, tax revenues are smaller and unemployment benefit expenditures are larger. However, once the economy returns to its potential level of output, both tax revenues and unemployment benefit expenditures return to normal.

Likewise, in a given year, one-off budgetary measures, such as bank bail-outs, can make the actual deficit larger. Or a temporary tax can bring revenues that make the budget position look better.

Excluding the impacts of these temporary factors from the annual budget balance to estimate the structural balance is therefore conceptually intuitive. The problem is that these estimations are really uncertain. A key source of error is related to errors in the estimation of the output gap. I analysed this issue here, using the revision of the initial estimate one-year later. In this post I use the same measure to analyse the revisions in structural balance estimates from the European Commission, IMF and OECD.

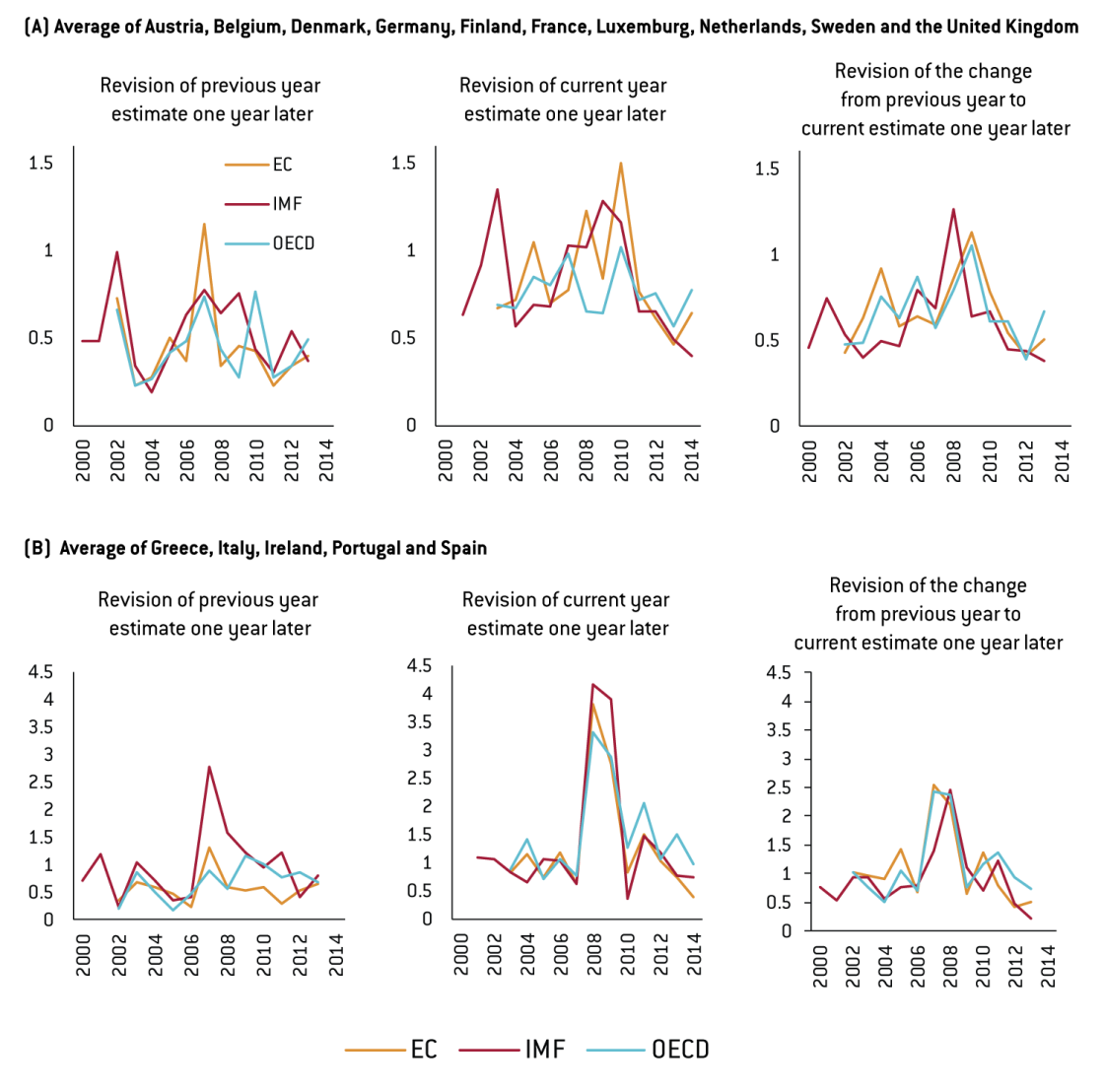

Figure 1 indicates major revisions. It also indicates that revisions by the three institutions are broadly similar, underlining the inherent difficulties in estimating structural budget balances.

Figure 1: Three measures of structural balance estimate revisions (% of potential GDP, absolute value)

Note: unweighted country averages of the absolute value of revisions (as % of potential GDP) are reported. Due to unavailability of some earlier European Commission and OECD structural balance estimates, the revision in the cyclically adjusted budget balance is reported for the first three years for the Commission estimates and for the first six years for the OECD estimates.

The first chart in both blocks shows the “revision of previous year estimate one year later”. For example, the final data point is the difference between the estimates for 2013 published in spring 2015 and spring 2014. These spring estimates are typically published by the IMF in April, by the European Commission in May and by the OECD in June, when budget data for the previous year is known with a reasonable precision. Despite that, estimates for the last year structural balances are revised quite significantly. These revisions are about 0.3-1.0 percent of GDP in ‘normal’ years, while in ‘crisis’ years revisions are much larger.

The second chart in both blocks shows the “revision of current year estimate one year later”. For example, the final data point is the difference between the spring 2015 and spring 2014 estimates for 2014. Since, for example, the spring 2014 estimate for 2014 involves forecasts, it is not surprising than revisions are larger than the revisions of the estimates for the previous year.

The third chart in both blocks shows the “revision of the change from previous year to current estimate one year later”. For example, the final data point is the difference between spring 2015 and spring 2014 estimates of the change in the structural balance from 2013 to 2014. There are major revisions in this indicator too, which are typically between 0.5-1.0 percent of GDP, while in ‘crisis’ years revisions are again much larger.

What does this mean looking ahead? Let us say, for example, that the Commission forecasts in May 2016 that a country’s structural balance will remain unchanged from 2015 to 2016. Then, in May 2017, when new estimates are published, it is likely that the Commission will estimate the 2015-2016 change in the structural balance to have been half a percent of GDP or larger (either an increase or decrease).

Half a percent of GDP is the usual adjustment requirement under the EU fiscal rules. I find it unacceptable that the EU’s fiscal framework strongly relies on an indicator (the change in the structural balance) for which the typical one-year revision in the estimate is larger than the required policy action.

Moreover, the figure above indicates revisions just one year later. Longer-term revisions (e.g. the difference between the 2015 and 2010 estimates for 2010) are even larger.

Revision of an estimate when new data becomes available is quite natural. Also, in some years the methodologies used to estimate potential output and the structural balance were revised. It is better to revise an initial estimate when it turns out later that it was incorrect than to continue using an incorrect estimate. But the problem is that the EU fiscal framework specifies short-term numerical targets for both the level and the change in the structural budget balance. Therefore, imprecision in the estimates can translate into fiscal policy decisions.

This imprecision in estimates of the structural balance was a key reason why, in a recent policy contribution with Gregory Claeys and Álvaro Leandro , we suggested that the EU should eliminate fiscal rules related to the structural balance. We propose a better fiscal rule, explained in detail in the policy contribution.