“Dura Lex, sed Lex”(?)

On the 30th of April, the Italian Constitutional Court issued a decision on the pension reform introduced by the Monti government in 2011. The decisio

On the 30th of April, the Italian Constitutional Court issued a decision on the pension reform introduced by the Monti government in 2011. The decision has potentially important implications for public finances, and sends also longer-reaching philosophical messages.

The Italian Constitutional Court said that one article in the pension reform law approved by the Monti government at the height of the crisis, is illegitimate. This article introduced a temporary block for 2012 and 2013 to pension indexation, for all entitlements above three times the minimum (i.e. all pensions about 1450 euro and above, in gross terms). The Court argued that this provision, however temporary, violates the principles of equality and proportionality.

The Government could potentially be bound to refund 4.5 million of pensioners.

The ruling is retroactive to 2012, meaning that the Government could potentially be bound to refund 4.5 million of pensioners for the lost indexation in 2012-2013. Comments by PM Renzi and Finance Minister Padoan suggest that the total cost, if the reform were to be completely scrapped, would be in the order of 18bn. This would take Italy’s 2015 deficit from the 2.6% of GDP forecasted by the government to 3.6% of GDP.

But the effective impact of this decision is more complex, as it stretches out into the future. Once the reimbursement for 2012-2013 will be paid, the basis on which future indexation will be computed will also be higher than forecasted in recent government budget documents. There seems to be at the moment no publicly available details of how much this would cost, but put in the context of the very high pension expenditures that Italy already faces, it can hardly be good news.

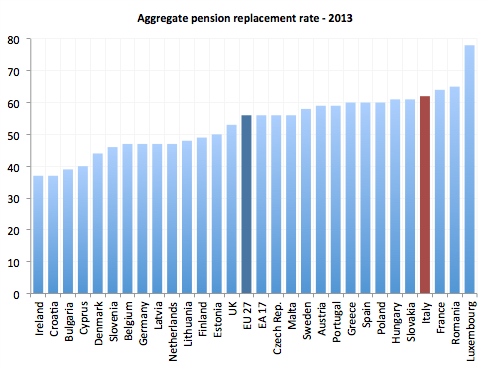

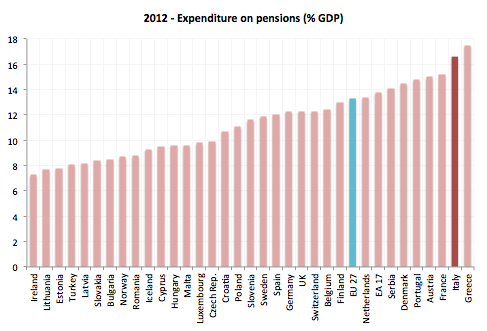

Figure 1a and 1b

Source: EUROSTAT

The Government’s strategy could still face challenges in court, but these will become clearer in the coming months. On the fiscal side, however, this decision already puts the government in a very delicate position. The reimbursements will in fact erode the “fiscal safety buffer” of around 2bn that the Government had succeeded in building up over the last months. This will be used to pay off indexation without running new deficit, thus winning a provisional support from the European Commission.This being the background, the government announced two days ago the strategy for the reimbursements. Of the 4.4 million of pensioners interested by the Constitutional Court’s decision, only 3.7 million will be refunded, i.e. all those with pensions above the minimum but below 3,200 euro per month. A previous ruling by the Court had deemed legitimate a temporary suspension of indexation imposed in 2008 for pension entitlements above 8 times the minimum (around 4000 euro), suggesting that, in this case too, it would be acceptable not to reimburse pensioners above above this threshold.

But the progress will no doubt be watched very closely, in Brussels. The IMF also warned in its concluding statement of 2015 Article IV mission to Italy, that “the re‐indexation of pensions in accordance with the Constitutional Court ruling should not modify the fiscal stance both this year and going forward. The safeguard clause should be fully offset by spending cuts—to avoid damaging tax hikes while building fiscal buffers.”

The Italian budget law foresees in fact a VAT hike of 2% as well as an increase in fuel taxes that can be triggered automatically to make sure the country achieves a structural budget balance by 2017 (the so-called “safety clause”). This tax hike would work against the Government’s recent limited expansions, at a time when the recovery in Italy is still fragile. In order to avoid it, the 2015 budget already foresaw 10 bn in expenditure cuts, which should reduce total expenditures from 51.1% of GDP in 2014 to 50.5% in 2015. The decision by the Constitutional Court, and the related deployment of the fiscal safety buffer, put an even higher pressure on the government to deliver on expenditure cuts.

The temporary de-indexation of pensions is against the principles of “equality” and “proportionality.

But beyond the budget, this decision send a more general, perhaps more important and controversial message. The Constitutional Court says in fact that the temporary de-indexation of pensions, even in time of dire economic crisis, is against the principles of “equality” and “proportionality”. Pensioners are certainly among those who were asked to bear a very significant part of the adjustments made during the crisis. This is true across countries in the “South” of the euro area, and it is far from who writes to deny this fact. But it may nevertheless be useful to put things into a broader perspective.

Italy is a country where the gap between young and elderly cohorts is wide and long-lived, but it has worsened during the crisis, with significant impact on the intergenerational redistribution. Pension expenditure in Italy is the second highest in Europe (figure 1b), standing at 16.5% of GDP even in 2012 (one of the years when this reform was in place). Perhaps more importantly, the replacement rate is top third, if we exclude Luxembourg that is clearly an outlier (figure 1a).

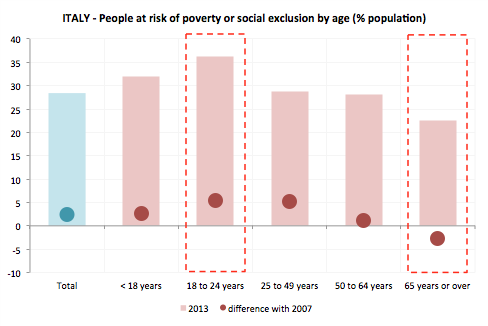

The percentage of elderly (65+) people at risk of poverty and social exclusion in Italy is around 22.6%. It is high, among the highest across the euro area over the same age range. For the younger cohorts the figure reaches 36.3% for the 18-24 years old, also among the highest in the euro area. The percentage at risk of poverty and social exclusion has increased by 5.4 percentage points among 18-24 years olds and by 5.3 percentage points among the 25-49 years old. It has decreased by 2.7 percentage points among the elderly.

This is by no means an special feature of Italy. Darvas et al. (2014) find that there has been during the crisis an increasing generational divide in Europe, as younger generations have suffered more than the elderly. The severe material deprivation rate has increased from 10.1 % in 2007 to 11.7 % in 2012 for children, while the same rate has declined from 8.6 % in 2007 to 7.5 % in 2012 for the elderly; 11.1 % of children lived in households in which their parents no longer work in 2012.

Source: EUROSTAT and own calculations

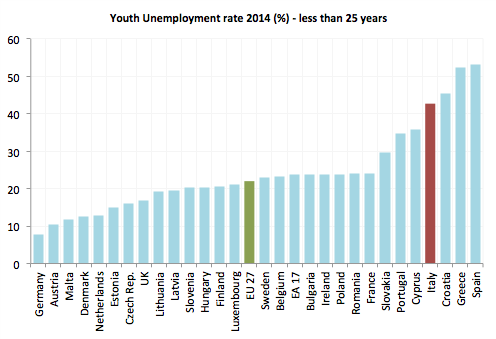

Youth (< 25 years) unemployment in Italy stood at 40% at the end of 201

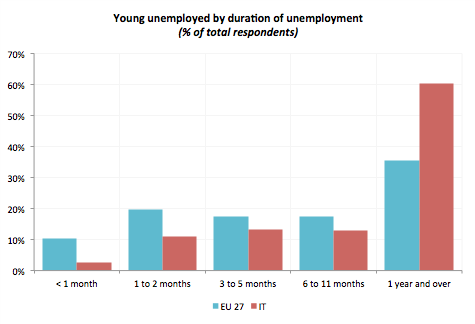

Figure 3 needs however to be put in the broader context of a country still suffering from a deep economic crisis that has had (and is still having) very serious consequences on the employment perspectives for young people. Youth (< 25 years) unemployment in Italy stood at 40% at the end of 2014, the third-highest in the euro area and the fourth-highest in the EU (figure 3a). Italy is one of the very few countries where youth unemployment has still increased (rather than declined) between 2013 and 2014, and the most recently available data from the National Institute of Statistics put the figure at yet a higher 43% in March 2015, signalling that the worrying trend is still far from stopping, not to mention reverting.

Figure 3a and b

Source: EUROSTAT

What is even more worrying, as already discussed previously, is that this very high youth unemployment is also a predominantly long-term phenomenon. In 2014, 60% of young unemployed had been unemployed for more than a year, against less than 40% at the EU level. This hinges heavily on the probability of future re-employment of these young workers, whose skills keep deteriorating as time goes by, but it will also have longer-term effects. In a pension system that shifted from Defined Benefit to Defined Contribution in 1995, a 40% youth unemployment rate maintained for a prolonged period of time also implies that a significant share of Italians who are young today will be entitled to very low pensions tomorrow.

So now, let’s put things in perspective. The Italian Constitutional Court decided that - in a country with the second highest pension expenditure and the third highest replacement rate in Europe - a temporary de-indexation of pension entitlements above three times the minimum violates the principles of “equality and proportionality”. As a consequence, the government will now deploy 2 bn in reimbursements for 3.7 million of pensioners, inversely proportional to the level of pensions. For the single pensioners, annual reimbursements for 2015 will thus range between 280 euro and 750 euro, which translates into 23 to 62 euro per month. Someone will argue that this can stimulate more consumption on the side of the beneficiaries. Possibly, it will. At the same time, however, it certainly wipes away the fiscal buffer that had been accumulated and it increases the risk of a VAT hike this year, which would adversely hit consumption across the board (not only for the restricted group of beneficiaries) and perhaps jeopardise the still weak economic recovery.

All this, in the context of a country that at present records a 43% rate of youth unemployment - 60% of which is long term and risks becoming structural. The decision also sends the message that budget constraints may be rendered de facto irrelevant, which might raise interesting questions about the solidity of article 81, enshrining the European budget balance rule in the Italian Constitution. And it also seriously question the legitimacy for a government to act resolutely on its budget, even in case of dire national emergency as it was in 2011, when not only italy but also the survival of the euro was at risk. The Court’s argument may be bullet-proof from a legal point of view - as the Romans used to say: “the law is harsh, yet it is the law”. But to the eyes of a humble economist, this looks ill-timed, hardly “proportional”, and conveying a peculiar interpretation of the term “equality”.