Blogs review: The when and how of exit strategies

What’s at stake: Markets trembled when minutes from the December FOMC meeting revealed that members had discussed the side effects of maintaining a $8

What’s at stake: Markets trembled when minutes from the December FOMC meeting revealed that members had discussed the side effects of maintaining a $85 billion pace of monthly asset purchases and the timing of its potential end. In a recent press conference, Ben Bernanke said “we may adjust the flow rate of purchases from month to month to appropriately calibrate the amount of accommodation” generating a number of discussions about the practicalities and implications of the Fed’s exit from years of quantitative easing.

Towards a gradual exit

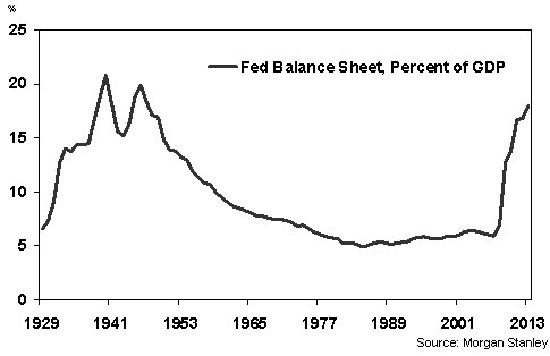

Real Time Economics writes that twice before the size of the Fed’s holdings have reached a share of the nation’s GDP comparable to where the central bank appears to be heading.

Ylan Mui writes at the Wonkblog that consensus is growing, inside the Federal Reserve, over the need to dial back the central bank’s $85-billion-dollar-a-month bond-buying program — but for very different reasons. It boils down to two sides: Hawks, who want to curtail quantitative easing programs because of the risks they create (see page 39 of the Monetary Policy Report for more on this). And doves, who see evidence that they’re working well enough at stimulating growth that they might soon no longer be needed.

Gavyn Davies notes that the markets are increasingly focused on whether the exit can be handled successfully (Sober Look writes that the exit strategy will drive the fixed income markets for years to come). In 1994, Alan Greenspan and colleagues believed that monetary policy had been behind the curve in previous economic cycles, and they saw virtue in acting in an unexpected way to maximize the effect of the policy change. But the consequences for a complacent financial system were extremely severe. When Greenspan had his next opportunity to tighten policy from 2004 onwards, he reassured the market that this would happen at a “measured pace”, but it is now believed to have taken place in an excessively gradual manner.

Timing and composition

Tim Duy writes that policymakers anticipate a gradual end to the program, and they want to communicate their intentions well ahead of the actual timing of the policy change. So expect them to continue to walk a fine line between acknowledging the exit strategy while making clear the exit is not imminent.

In a recent paper, several economists at the Federal Reserve Board provide a framework for projecting Federal Reserve assets and liabilities and income through time. The authors base their projections on the general principles for the exit strategy that the FOMC outlined in the minutes of the June 2011 FOMC meeting. The Committee stated that it intended to take the following steps in the following order:

1. Cease reinvesting some or all payments of principal on the securities holdings in the System Open Market Account portfolio—that is, its holdings of securities;

2. Modify forward guidance on the path of the federal funds rate and initiate temporary reserve‐draining operations aimed at supporting the implementation of an increase in the federal funds rate when appropriate;

3. Raise the target federal funds rate;

4. Sell agency securities over a period of three to five years; and

5. Once sales begin, normalize the size of the balance sheet over two to three years.

The politics of exiting

Gavyn Davies writes that the politics of paying less money to the Treasury and more to the banks will be very difficult.

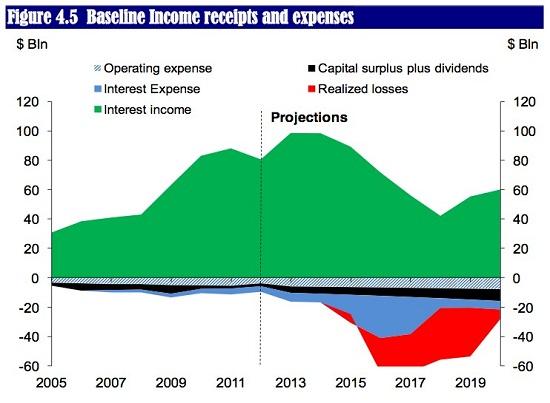

James Hamilton illustrates that if the Fed is buying assets when long-term rates are low, and selling them when rates have risen, the Fed will make a capital loss on its purchases (the red region on the graph below). The Fed will also have to be paying more in interest on reserves as rates rise (the blue region below). According to the baseline calculations of the authors, during 2017-2019 these expenditures for the Fed will be greater than income coming in from interest on retained assets (the green region in the graph above).

Source: Hamilton and al. (2013)

James Hamilton, however, notes that – under their baseline scenario – the Fed's profits in its good years exceed its losses in its bad years. For this reason, Brad DeLong disagrees with Gavyn Davies and thinks that the politics will not be difficult.

John Cochrane notes another difficulty: monetary policy depends on fiscal policy in an era of large debts and deficits. Suppose that the Fed raises interest rates to 5% over the next few years. This is a reversion to normal, not a big tightening. Yet with $18 trillion of debt outstanding, the federal government will have to pay $900 billion more in annual interest, something that will be hard to swallow for Congress.

The How: IOER, Reverse repos, Term deposits…

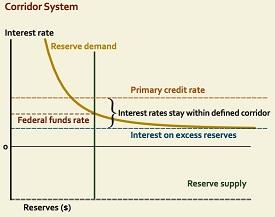

The Monetary Policy Report of the Federal Reserve explains that it will be able to put upward pressure on short-term interest rates at the appropriate time by raising the interest rate it pays on reserves, using draining tools like reverse repurchase agreements or term deposits with depository institutions, or selling securities from the Federal Reserve’s portfolio.

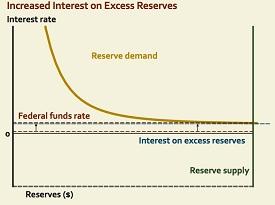

Mark Sniderman – Executive Vice President of the Cleveland Fed – writes that the Federal Reserve can use the power granted by congress to pay interest on reserves to immobilize some portion of the excess reserves until it can remove them from the balance sheet through other means. By increasing the interest rate paid on reserves, the Federal Reserve can also raise the federal funds rate while holding the same level of reserve supply as before. That’s because the interest rate on excess reserves puts a de facto floor under the demand for reserves in the banking system—banks won’t want to trade with one another at the federal funds rate, even as it rises, if they can get a better rate by keeping excess reserves on deposit at the Federal Reserve.

|

|

Source: Cleveland Fed

As the economy recovers, the Federal Reserve may want to continue increasing the federal funds rate. To do so, the Federal Reserve could first raise the interest paid on excess reserves. Then, to manage the supply of bank reserves, any or all of three other tools could be put to use:

1. Term deposits – banks put money on deposit for a specified term, such as three months.

2. Reverse repos – the Federal Reserve lends out securities from its portfolio and banks use reserves on deposit as payment, keeping those reserves out of the marketplace.

3. Redemption of maturing MBS or their outright sale.

Sober Look writes that back in 2009 the Fed set up tri-party repo arrangements with a number of dealers. Eventually that will allow the central bank to lend out the securities instead of selling them. As dealers borrow the securities over a period of a week for example, they post cash as collateral to the Fed (dealers pay the coupon on the securities they borrow and receive the market repo rate on their cash “collateral”). That cash going into the repo account is taken out of “circulation”, thus draining the reserves. If the Fed rolls these repo positions over time, the reserves will stay “drained” but the securities will still be owned by the Fed - until they pay down or mature.

Jeremy Siegel writes that by increasing required reserves, the Fed’s strategy to regain control over the level of deposits can be made easier. The Fed has not altered reserve requirements in more than 20 years and has not raised any reserve ratio on any deposit in almost four decades. The Fed’s Flow of Funds Account indicates that total deposits in financial institutions were $10.6tn at the end of 2012. This implies that a 15 per cent reserve requirement on deposits would absorb almost all the excess reserves now in the banks.