Blogs review: The stock market recovery

What’s at stake: The strengthening of the U.S. economy was reflected last week by a positive jobs report with America adding 236,000 more jobs in

What’s at stake: The strengthening of the U.S. economy was reflected last week by a positive jobs report with America adding 236,000 more jobs in February than it had in January, and an unemployment rate down to 7.7%. The past week was also marked by new highs in stock market valuations, which generated discussions about the sustainability of these improvements, the role of monetary policy in driving equity prices and the impact of stock market valuations on the rebuilding of household balance sheets.

The stock market in a historical perspective

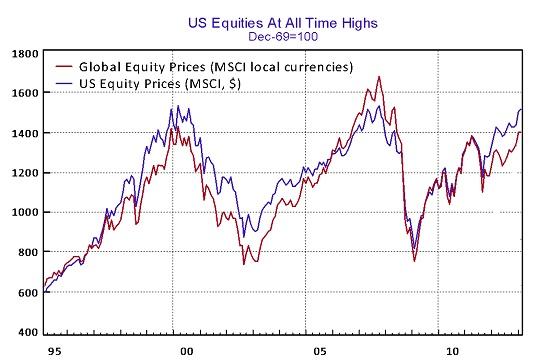

Ryan Avent writes that there is no denying that equities are having a good run. True, the press reports have mostly focused on the Dow, which is not the best-constructed index, is not a one-stop shop for assessments of the American economy. And yes, adjustments for inflation and dividends leave a slightly different picture of where the Dow is relative to past levels. But, as noted in the print edition of The Economist, Wall Street is not alone. Stock markets in the developed world have been in fairly buoyant mood since the start of the year with the MSCI World Index rising by 5% in the first two months of 2013, and the Japanese market gaining 13.5%. Emerging markets, in contrast, have been flat.

Source: Gavyn Davies

Justin Lahart (HT Mark Thoma) notes in the Wall Street Journal that with dividends reinvested, the Dow would now be at 16,600. Adjusting for both inflation and dividends would put the Dow industrials around 15,000.

What will come next

Gavyn Davies writes that investors are naturally very focused on whether equities, having failed twice before to break above current levels, can finally overcome vertigo and sustain a bull run into unprecedented territory.

Neil Irwin notes that the last time the S&P lodged a four-year gain as strong as the current run was from late 1996 to late 2000, which was, with hindsight, a time of an epic bubble. Given that the current market boom has been fueled in no small part by easy money policies out of the Federal Reserve, there’s some simmering worry that this too is a bubble—perhaps that the minute the Fed starts inching away from the era of cheap money, the whole thing will collapse in upon itself. But there’s good evidence pointing to this not being the case. The key thing to know is that American businesses have spent the last four years becoming much more profitable.

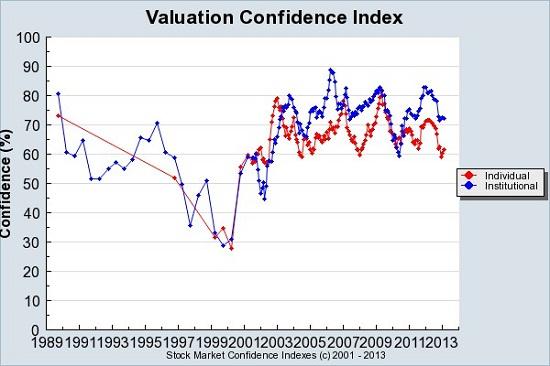

Robert Shiller sends us to an index that he has developed with colleagues at the Yale school of management. It is the percentage of respondents who think that the stock market is not overvalued. Using the six-month moving average ended in February, it was running at 72 percent for institutional investors and 62 percent for individuals. That may sound like a ton of confidence, but it isn’t as high as the roughly 80 percent recorded in both categories just before the market peak of 2007.

Source: Yale School of Management

Robert Shiller uses a measure of stock market valuation that he developed more than 20 years ago with Prof. John Campbell of Harvard, called the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio, or CAPE. It measures the real, or inflation-adjusted, Standard & Poor’s 500 index divided by a 10-year average of real S.& P. earnings. The CAPE has been high of late: it stands at 23, compared with a historical average of around 15. This suggests that the market is somewhat overpriced and might show below-average returns in the future.

The print edition of The Economist notes that an alternative measure, the Q ratio, which compares shares to the replacement cost of net assets, shows the American market as 50% overvalued, according to Smithers & Co, a consultancy.

Monetary policy and the search for yield

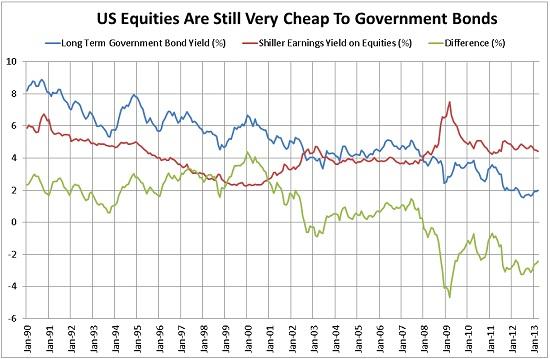

Neil Irwin writes that the S&P is yielding 6.7 percent right now (this is just 1 over a P/E ratio of 14.8). Now compare that yield of 6.7 percent to what a risk-free asset is paying right now. For 10-year Treasury bonds, that’s 1.8 percent. The gap between those two numbers, nearly 5 percentage points, is, in effect, the extra compensation investors receive for investing in risky stocks instead of safe bonds. For comparison, look at what that same gap (the equity risk premium, to use the finance geek term) has been at some other key moments. In the summer of 2007, the stock market earnings yield was 5.8 percent, lower than it is now, though not drastically so. Yet at the time, 10 year Treasury bonds were yielding 5.1 percent. And the current boom has almost nothing in common with the bubble that ended in March 2000. At the peak of that boom, the S&P had an unprecedented price to earnings ratio of 31.4, which translates into a 3.2 percent earnings yield. At the time, Treasuries were yielding 6 percent.

Source: Gavyn Davies

Mark Thoma writes that the policy of the Fed has created an increase in demand that has helped to drive up stock and bond prices. In addition, monetary policy has helped to boost the economy, in part through greater spending induced by this "wealth effect" from higher asset prices, and this has a feedback effect that further increases asset prices.

The stock market and the real economy

Yih Lin Teh and John Hawksworth note at the PwC blog that, from November 2012 to the end of January 2013, major stock markets experienced relatively strong gains – in marked contrast to negative GDP growth in most of the major advanced economies in Q4 2012.

Paul Krugman writes that the high level of stock prices is, in large part, a reflection of the growing disconnect between productivity and wages. While the economy remains deeply depressed, corporate profits have staged a strong recovery. Not only are workers failing to share in the fruits of their own rising productivity, hundreds of billions of dollars are piling up in the treasuries of corporations that, facing weak consumer demand, see no reason to put those dollars to work.

Mark Thoma the relationship between the stock market and the economy is not very reliable and stock market values only explain a small proportion of the total movement in variables like GDP and employment. Thus, while it's very likely that the recovery will continue at its slow pace, that prediction has little to do with recent movements in stock prices.

The improvement in household balance sheets

Neil Irwin writes at the Wonkblog that the rise in the stock market is a major, major reason that Americans’ household finances are looking better. Stock investments and mutual funds only amount to about 20 percent of Americans’ assets, according to data from the Federal Reserve; much more of their money is tied up in their houses, other physical assets like cars, bank accounts, life insurance policies, and the like. Yet between 2008 and the third quarter of 2012, they accounted for 59 percent of the $10.6 trillion rise in American households’ assets. Americans—at least those with significant savings—are feeling wealthier, and the booming market is a big part of the reason. Household real estate, by contrast, is still worth less than it was in 2008 even after edging up recently.