China’s growing presence in Latin America is a problem for the West

For a long time, almost everything that has happened in the Latin American region has been connected to China. When China became the world’s main buyer after putting its economy on steroids to protect it from the effects of the global financial crisis in 2008, the relationship between both countries began with commodity trading.

Since then, China has flooded Latin American countries with its exports of consumer goods and in recent years, they have sold intermediate products such as machinery, electronic components and many other commodities to Latin America. China has done this by competing directly with the United States and a Europe that, for decades, had benefited from its global export power.

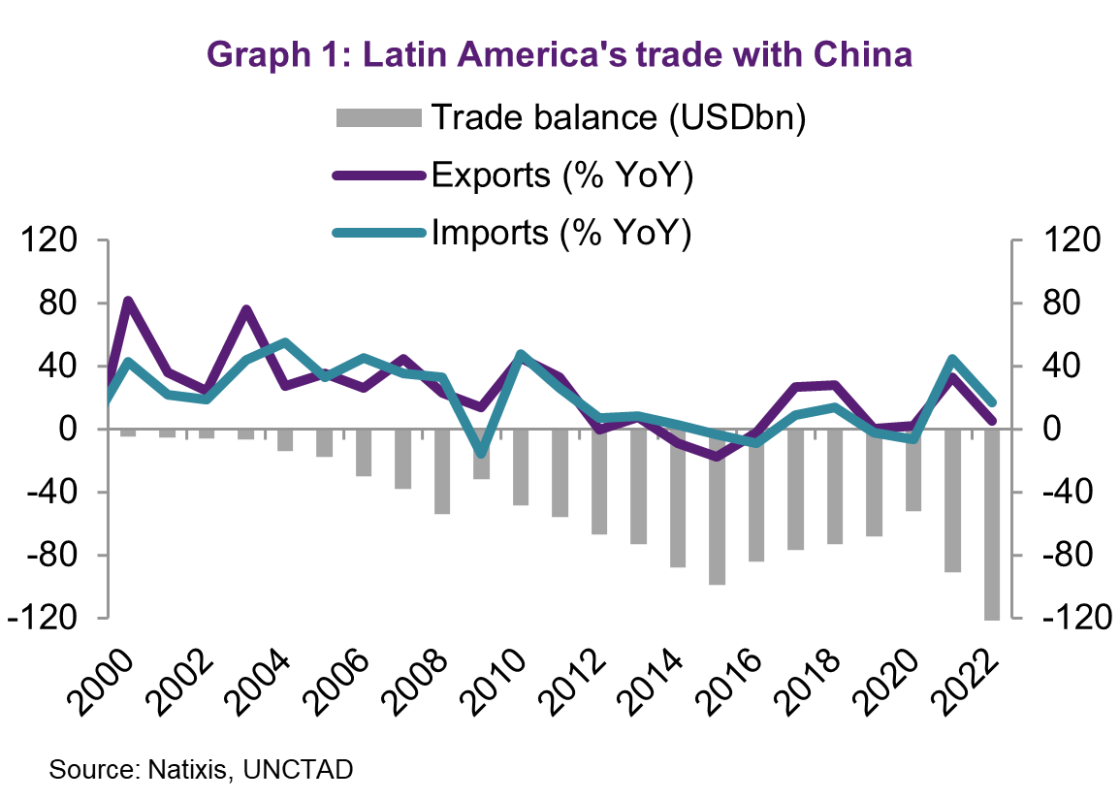

When most Latin American countries began to accumulate trade deficits with the Asian giant, China began to develop a second level of economic influence in the form of direct investment. Despite China’s competitiveness in the manufacturing sector, it has actually been Chinese companies within the electricity sector that have dominated Latin America. China has also heavily invested in the quest for control of natural resources. China has not yet developed manufacturing capacity in the Latin American region and more worryingly, Latin America’s trade deficit with China has ballooned since the pandemic began (Graph 1).

Beyond direct investment, China’s share of infrastructure construction in the region has been financed by loans from its big development banks, which has only increased Latin American debt to China. In fact, in some cases the accumulation of debt has been so rapid that it has ended up in the need to restructure it, which is what happened in Ecuador. In the same way as the piling up of loans happened very fast, the burst of that credit boom happened even faster. Since 2019 – a year in which the strategic competition between China and the US accelerated – China has drastically reduced its lending overseas, including to Latin America.

Diplomatic advances

Having reached a much broader level of economic relations, we should not be surprised that China has also been able to advance its diplomatic relations with much of the region. Indeed, in recent years, several Latin American countries that still had ties with Taiwan have turned to Beijing. Panama is a prominent example because of its strategic importance derived from the Panama Canal. Enormous uncertainties surrounding diplomatic relations remain for the few Latin American countries that still support Taiwan. This was reflected in the recent elections in Paraguay. But it’s not just Taiwan. Political trends in the region are undoubtedly being influenced by China, as evidenced by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s election campaign in Brazil and his foreign policy. More generally, the winds of left-wing populism are getting stronger, with a view to an alternative model of development in which the state plays a greater role.

While China’s influence may seem unstoppable on its own, the reality is that both the US and the European Union have enabled this influence. Neither economic bloc have taken the importance of reaching trade and investment agreements with Latin America seriously enough and have been losing influence in the region as a result.

In the case of the US, the financial crisis undoubtedly left a dent in the average citizen’s appreciation of the benefits of international trade. In the EU, the lack of an agreement with Mercosur after more than 20 years of negotiations is paradigmatic of the difficulties that an economic area, rather than a sovereign one, has in a world where international trade rules are broken and in which member countries are not willing to make the necessary concessions to move forward.

Beyond trade agreements, it is difficult to see how the EU can maintain an influence commensurate with its economic size – which, incidentally, is also shrinking in relative terms – with an institutional framework so complicated that it opens Europe up to the status quo .

It is easy to blame China for Western powers’ loss of influence in the Latin American region, but the reality is that Beijing has only taken advantage of the opportunity the West has carelessly abandoned.

The question is whether the West’s change of strategy toward China, which advocates reducing the risks inherent in its critical dependence on the Asian giant for some key sectors such as the energy transition, could also have consequences for the West’s strategy toward Latin America, a region which has abundant critical raw materials for the energy transition.

What does this mean for the European Union?

Europe has important historical and cultural ties with Latin America and was Latin America’s major source of foreign direct investment in the past . The EU has spent decades negotiating a new phase of the trade agreement with Mexico, which was first reached when Mexico entered NAFTA. In the same vein, the EU has been negotiating a trade and investment deal for over twenty years the Mercosur while China’s influence kept on growing in the region. Ironically, as the EU was losing influence in Latin America, European trade deals have become increasingly complex with greater importance attached to climate change and human rights.

Whether Latin America will stand ready to accept such conditions – at the same time in which China launches numerous initiatives for Latin America as part of the Global South – looks increasingly doubtful. High expectations built around reaching an agreement during the Spanish Presidency of the EU this semester might not be fulfilled because of this. The next few months will be key to determine whether the EU is ready to upgrade its economic relations with Latin America or risk further losing its influence.

ZhōngHuá Mundus is a newsletter by Bruegel, bringing you monthly analysis of China in the world, as seen from Europe.

This is an output of China Horizons, Bruegel's contribution in the project Dealing with a resurgent China (DWARC). This project has received funding from the European Union’s HORIZON Research and Innovation Actions under grant agreement No. 101061700.