Capital flight in the Euro area: from bad to worse

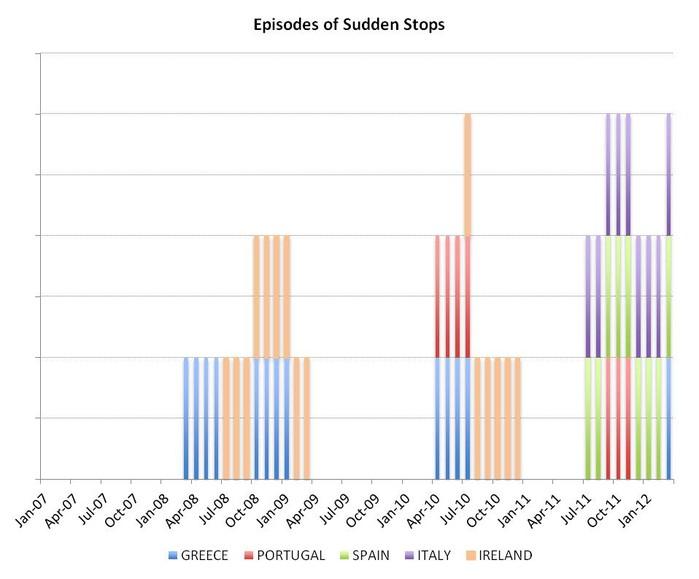

In a recent policy contribution we investigated the dynamics of capital flows in five Southern euro area countries. We found that Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy all experienced significant private capital inflows from 2002 to 2007-2009, followed by unambiguous and rather sudden outflows. The sudden stops are concentrated in three waves (figure 1): the global financial crisis in 2008/09; spring 2010 in correspondence to the Greek Programme and summer 2011. Updated figures show that the latest wave of sudden stops is still ongoing, with the reversal of capital flows affecting especially Italy and Spain.

Figure 1

Source: authors calculations

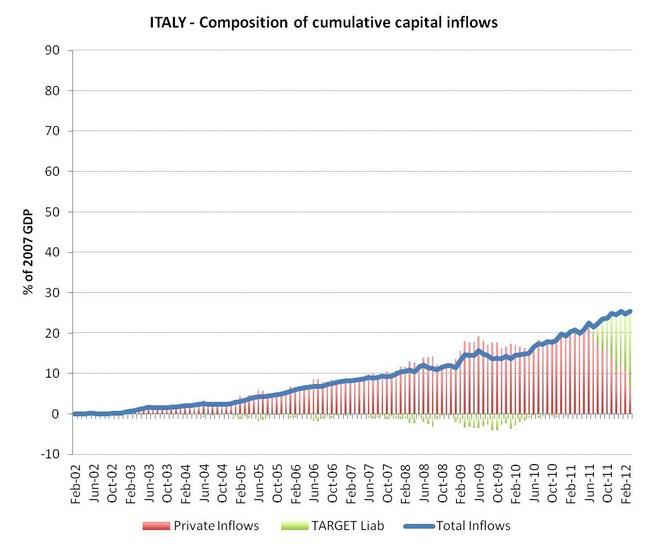

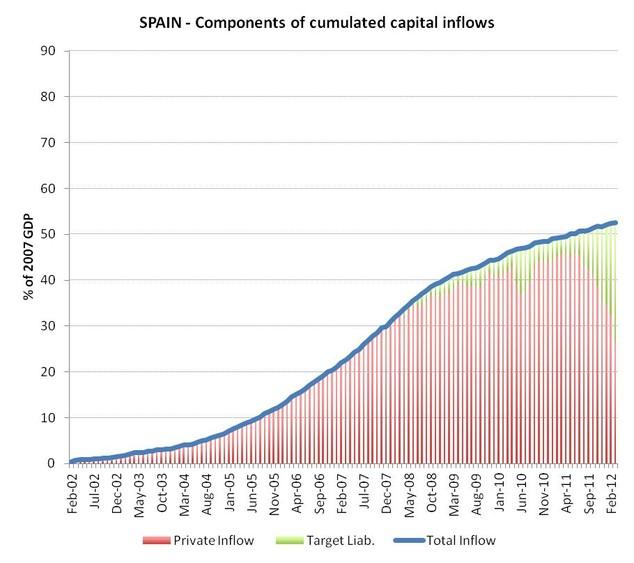

These reversals are large enough to qualify as a “sudden stops” (a common feature of balance-of-payment-crises in emerging countries) but have been cushioned by equally sizable inflows of public capital flows, namely the disbursement of EU/IMF programme and (or exclusively, in the case of Italy and Spain) the liquidity provided by the Eurosystem (figure 2).

Figure 2 – Private and public capital flows in Italy and Spain

Source: authors calculation with data from National Central banks

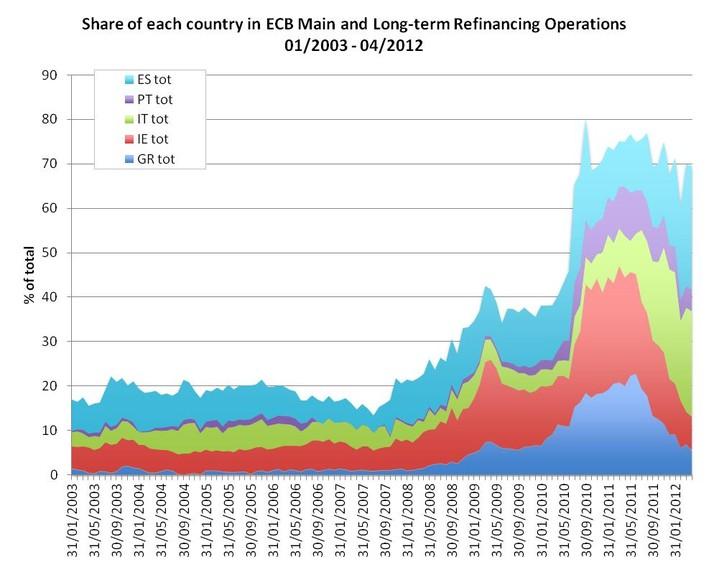

Updated statistics show that the situation is not improving. During the last months of 2011 and the first months 2012 the private capital flight from the periphery has accelerated, affecting especially Spain and Italy. As a consequence, in these countries the reliance of banks on Eurosystem liquidity has grown to unprecedented levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Use of Eurosystem liquidity by country (share of total LTRO + MRO)

Source: authors calculation with data from National Central banks

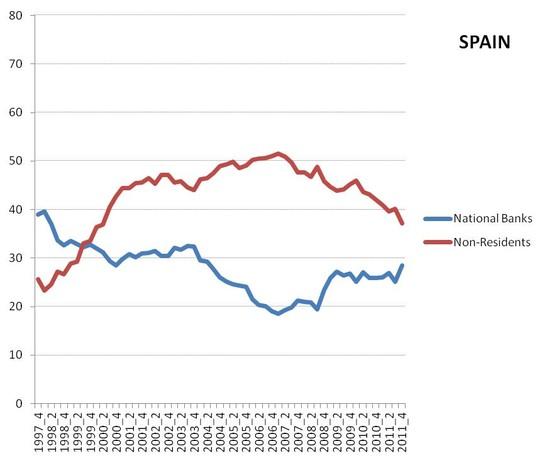

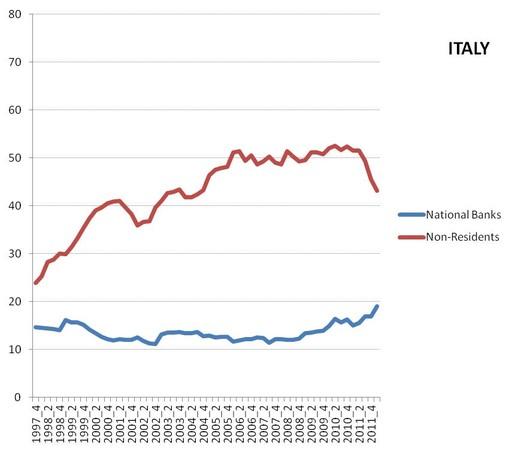

An interesting question in view of such evidence is what banks have been doing with the huge amount of liquidity they have received from the Eurosystem. Earlier this year, we showed that since the beginning of the crisis domestic banks have been increasingly substituting non-residents in the holding of peripheral countries’ government securities. An update of the underlying data (figure 2) suggests that this trend is continuing – if not accelerating – in Italy and Spain.

Figure 4 – Share of domestic banks and of non-residents in total holding of government securities (Italy and Spain)

Source: authors calculation with data from National Central banks

The outflow from the peripheral government capital markets has been impressive and the flight from the government bond markets constitutes a large (even if not exclusive) part of it. What is even more worrying, is that in almost all the countries in trouble, the share off loaded by non-residents is being constantly taken up by domestic banks[1]. This move – advocated explicitly by some politicians at the end of last year – increases the vulnerability of euro area countries. By reinforcing the sovereign-banking vicious cycle it deepens the crisis of confidence that has been driving private capital out of the periphery in the first place, rising at the same time serious doubts on the effectiveness of the Eurosystem’s extraordinary measures in tackling the roots of the problem.

References

Merler, S. and Jean Pisani-Ferry (2012) – “Who’s afraid of sovereign bonds?”, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2012|02, February

Merler, S. and Jean Pisani-Ferry (2012) – “Sudden Stops in the Euro area”, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2012|06, March

[1] Italy is to some extent an exception, because non-financial residents have absorbed a large part of the significant drop in non-resident bond holdings.