Blogs review: The welfare state during times of economic crisis.

What’s at stake: The current economic crisis has led to increased unemployment and put sharp pressure on government budgets. The welfare state can hel

What’s at stake: The current economic crisis has led to increased unemployment and put sharp pressure on government budgets. The welfare state can help mitigate the effects of the crisis on citizens, particularly through provision of unemployment insurance, but will also strongly be affected when budget consolidation is to occur through spending cuts. Furthermore, particularly American right wing commentators argue that European welfare states are root causes of the present sovereign debt crises. This review focuses on the perspectives for welfare states, particularly in Europe, under conditions of government budget consolidation.

The OECD Working Party of Senior Budget Officials finds that 8 out of 23 OECD countries require an improvement in the primary balance of more than 10% of GDP to stabilise debt at 60% of GDP by 2025. Renewed growth alone will not be sufficient to stabilise government debt. Spending cuts provide the most durable reduction of deficits and should be emphasised in consolidation plans – and indeed they are. Being major spending items, welfare, health and pensions expenditures are most targeted (in frequency terms) by countries’ consolidation strategies.

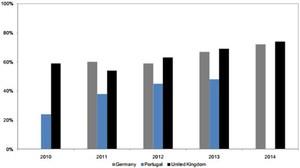

Proportion of spending cuts in austerity packages over time:

Source: OECD (2011)

Is the European Social Model dead?

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Mario Draghi declared that the European Social Model no longer exists. High youth unemployment exists in countries with dual labour markets. Labour law must become more flexible and fairer at the same time. Europeans are no longer so rich that they can pay everybody to do nothing. With fiscal consolidation inevitable, good consolidation will involve lower taxes and lower government spending focused on infrastructure and investment to foster future growth through incentives and productivity.

Philippe Mabille supports this view. Any move away from the austerity programmes would immediately ruin market confidence, raise interest rates on government bonds and further complicate a consolidation of public finances.

Iain Begg believes Draghi overstates the point: the proper response to the crisis is not a dismantling, but a reshaping of European welfare systems, making them more effective while preserving their core values and features. One part of this reshaping is a liberalisation of labour markets and a curbing of welfare benefits for inactivity. The second part is a move in the direction of activating social policies: child care, training schemes and efficient health programmes all contribute to competitiveness of European economies. Flexicurity policies, where pursued, have performed well in the crisis and should be seen as the future of the European Social Model. Anton Hemerijck et al. make a similar point.

Why did the Nordic welfare states get through the crisis so well?

Nima Sanandaji writes that the reason for the Swedish success in the crisis is not the welfare state but the relatively high degree of economic freedom. The creation of the Swedish welfare state in the post-war period reduced economic dynamism. The good performance in the crisis is mainly due to market-oriented reforms enacted by the present government.

Drawing lessons from Sweden’s reactions to the crisis in the 1990s, Richard Freeman et al. argue that the essence of the Swedish success lies in a pragmatic approach to welfare state reform, reducing benefits with substantial efficiency costs. Policy innovation aimed at welfare state efficiency enables combining equality with efficiency outcomes. However, the lessons are not easily transferable to larger and more heterogeneous countries such as the US, where egalitarian objectives do not enjoy as widespread support. The key ingredient of the Swedish recipe is policymakers who are able to find and implement creative and efficient solutions to problems facing the social system.

Carlos Joly and Per Ingvar Olsen argue that the success of the Nordic model of welfare states is replicable by other countries. Key to success is not the kind of society in Scandinavia, but the setup of the system. Institutionalised egalitarianism ensures that benefits from growth accrue to the broad population. This in turn allows the adaptive capabilities that drive the economic success: highly cooperative industrial and activating social policies.

The Greek situation:

Manos Matsaganis writes that the Greek welfare state was characterised by a huge bias towards pensions and privileges for some occupational groups, leading to low efficiency in achieving distributional outcomes. Inability to address the demographic challenge inherent in the pensions system contributed to the crisis. Now, the welfare system is in very poor shape to deal with the unemployment effects of the crisis. The unemployment insurance system has inadequate coverage for those workers not in privileged positions on the labour market. No minimum income system exists. An emergency agenda for reforming the welfare system should focus on extending the coverage of the social safety net to those in real need while generating savings from removing unwarranted privileges.

Convergence of welfare states in the crisis?

Kevin Farnsworth and Zoë Irving argue that the economic crisis will widen the gulf between countries with a commitment to social welfare and those without. Least hit by the crisis in terms of fiscal consolidation needs are the Social Democratic and Continental welfare states with their relatively generous welfare systems. The strong impact of the crisis on the Southern and Liberal Market Economies with limited welfare states, coupled with fiscal consolidation largely occurring through spending cuts, will lead to further cutbacks in the least developed welfare states.

Arne Heise and Hanna Lierse compare austerity packages in the EU and find a large divergence in cuts to welfare spending between nations. Even in countries with already low welfare spending such as the UK, Latvia or Romania, further cuts are planned, making a convergence to common standards without coordination unlikely. Consolidation plans are generally structured to have regressive distributive impacts with cuts most affecting the least well-off.

Peter Starke et al. look at social policy responses to three major crises, including the present one, in Australia, Sweden and the Netherlands and derive some general dynamics: Often, the initial response to a crisis is expansion of the welfare state to mitigate the effects of the crisis, followed by successive retrenchment when fiscal effects become overbearing. In small welfare states, where little automatic stabilization occurs, expansion of the welfare state during crisis is more likely than in large welfare states, where retrenchment dominates as crisis response, prompted by the large fiscal effect that a crisis creates in a large welfare state. Crises may thus indeed foster welfare state convergence.

Daniel Mertens and Wolfgang Streeck are afraid that useful “social investments” will be omitted under austerity. Shifting expenditures towards education, active labour market policies and family assistance would foster the build-up of human capital and innovative capacity. But the examples of Germany, Sweden and the US show that budget consolidation in times of crisis led to reductions of social investments, particularly where they previously were large. Through crises, social investments may thus converge to an undesirably low equilibrium.

Did welfare states cause the crisis?

Rob Samuelson argues that we are really witnessing a crisis of the European welfare state. Europe’s turmoil was inevitable, even if the euro had never been created. The welfare state had grown too large to be supported economically. As deficits rise, economic instability will increase and growth will decline. Paying promised benefits becomes harder, austerity becomes unavoidable. The welfare state, designed to improve security and dampen social conflict, now looms as an engine for insecurity, conflict and disappointment.

In a similar vein, Frederik Erixon argues that the expansion of government spending in Greece, Spain and Portugal during bubble growth pushed the countries into crisis when the bubble collapsed. These countries have no other way out of the crisis but by radically cutting government expenditures. However, cutting the welfare state will become necessary in future for countries not in crisis today such as Germany or Denmark. They, too, will run into funding problems of their large welfare states.

Ezra Klein objects: Firstly, the costs of a welfare state are not a good measure of its extent. The US has less healthcare provision than Canada, but at far greater cost. And secondly, whilst Germany has more social spending than Greece, Greece is in trouble, not Germany. The crisis is one of growth and institutions, not of the welfare state.

Dean Baker points out to reporters that the idea of large welfare states causing the crisis is inconsistent with the crisis we are facing: “the bloated welfare state story is too much demand chasing too few resources. The problem today is too little demand chasing too many resources, hence the mass unemployment. Remember this one and you are ahead of 99 percent of your peers.”

*Bruegel economic blogs review is an information service that surveys external blogs. It does not survey Bruegel’s own publications, nor does it include comments by Bruegel authors.

*Bruegel economic blogs reviews are also available on the Bruegel blog.