How best to ensure international digital competition cooperation

International cooperation on digital markets must ensure competition cases and laws around the world are consistent.

Executive Summary

Large digital firms pose similar competition issues worldwide, such as promoting their own services over those of rivals, or imposing unfair terms and conditions. Competition authorities have opened several antitrust investigations and policymakers have proposed digital competition regulations to tackle these issues.

G7 competition authorities have called for several years for international cooperation on digital markets. They want competition cases and laws around the world that are consistent and work together.

However, the question of how this can be done remains. A toolbox for international cooperation in competition enforcement already exists, but it does not provide for cooperation in competition policy and has shortcomings in relation to competition enforcement.

Current and proposed legislation targets the largest digital firms to tackle the characteristics of digital markets, such as multi-sidedness, and the same or very similar behaviours, such as self-preferencing. Legislation in different jurisdictions addresses these issues with similar rules. While there is some convergence, some rules diverge in substance and some are at high risk of divergence in interpretation. Inconsistency is thus likely to arise from a divergence of interpretation rather than substance.

The solution would be to ensure a coherent approach to competition in digital markets. This could be done by developing a framework based on four elements: (1) adoption of common legal phases for future digital competition laws to ensure clarity; (2) adoption of a common legal interpretation through guidance drafted by international forums, such as the International Competition Network (ICN); (3) adoption of common technical requirements developed in the context of ICN technical workshops, when the rules require it; and (4) the implementation of an international monitoring committee within the ICN to evaluate whether competition authorities and courts enforce the rules consistently. The impact of the framework might be limited because of the non-binding nature of the approach, and the focus on specific competition-related legislation, excluding laws that can also address the issues, such as civil law. Countries can overcome these limitations if they are willing to cooperate to ensure a consistent approach.

1 Introduction

Competition policy and enforcement in digital markets is still the priority for lawmakers and competition authorities worldwide. In the last few years, antitrust investigations and new digital competition laws have proliferated. They aim to tackle several anticompetitive concerns in some digital markets that are concentrated in the hands of just a few large online firms: Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Facebook (Meta), Apple and Microsoft (the ‘GAFAM’). For several years, competition authorities have called for more international cooperation in regulating digital markets. Since 2019, they have met annually in the context of the G7 to discuss how to foster cooperation to ensure a consistent approach in digital markets (G7, 2019). As noted by the president of the German competition authority in the context of the G7 Digital Competition Summit on 12 October 2022, under the German G7 presidency, “we need coherent approaches, remedies that have impact, and interdisciplinary thinking, particularly where data practices come into focus”[ 1 See Bundeskartellamt press release of 12 October 2022: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilunge…. ].

But how can this be done? A toolbox for international cooperation in competition enforcement already exists (OECD and ICN, 2021). The tools include informal and formal cooperation, formal agreements, regional enforcement cooperation, notification of planned or current investigations, consideration of the interests of other jurisdictions, assistance in investigations and enhanced cooperation such as resource-sharing and work-sharing. However, these tools do not ensure cooperation in competition policy and face several challenges, including legal challenges, in relation to competition enforcement. Moreover, the problem of cooperation relates to the interpretation of the competition concern, rather than to the substance of the rules. The goal is thus to ensure interoperability, so that different legal rules work seamlessly together to achieve the same outcome. This can be done by developing a framework that enables different competition laws to work together.

The remainder of this policy contribution is as follows: section 2 outlines the challenges in digital markets and how competition authorities have responded. It stresses that G7 economies are investigating the same or very similar competition concerns, and have adopted or are planning to adopt specific laws to deal with them. Section 3 then sets out a solution in the form of a framework for interoperability between the various antitrust and digital competition rules.

2 Competition issues in digital markets

2.1 Challenges

Characteristics of digital markets

In the digital economy, firms often provide services to at least two distinct groups of consumers in so-called multisided markets composed of end-users, who most of the time benefit from zero-price services, and business users that pay to reach them. In that setting, the firm is a platform that plays the role of an intermediary between users. These markets rely on the interaction between the groups attracting users within and between groups, resulting in positive or sometimes negative direct and indirect network effects.

Social media is a typical example. End-users attract other end-users (direct network effects), which in turn attracts business users (indirect network effects). The interaction leads to the creation of a high volume and variety of personal and non-personal data that firms collect and often process in real-time to derive valuable insights. In turn, data enables the firms to offer personalised services to users and to develop new services.

The development of services requires high sunk costs, but nearly zero variable costs, leading to extreme economies of scale in which serving one additional user is costless. The firm often combines data between its various services that interact together seamlessly, leading to extreme economies of scope and the creation of digital ecosystems consisting of multiple services. The classic example is a general search engine that provides search functions for specific queries, such as shopping, by using data from general search. Another example is digital mapping, displaying information from a general search, such as the location of restaurants (Crémer et al, 2019; Cabral et al, 2021). Firms exploiting these characteristics become inevitable gateways for business users and end-users, who are locked-in into the firm's services because they have no choice but to use the service if they want to interact.

For instance, a LinkedIn user must be on LinkedIn to reach other users, unless they persuade all their followers to use a rival service. Nonetheless, users sometimes use more than one provider for the same service – ie multi-homing – thus reducing lock-in effects. For instance, users typically use several messaging services, such as Meta-owned WhatsApp, Meta-owned Instagram and Meta-owned Facebook messenger.

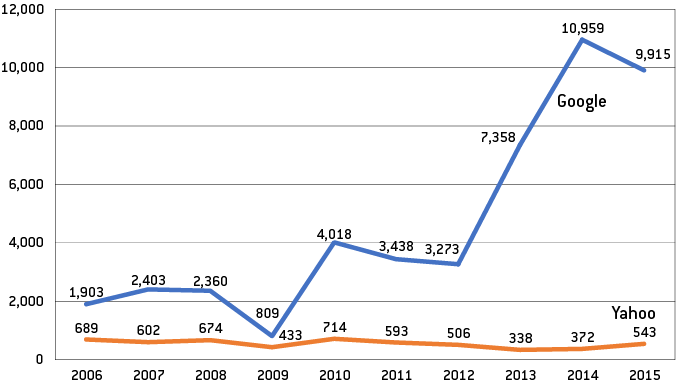

Finally, firms generate significant revenues from the provision of products/services at global level, enabling them to invest significantly in a way that rivals and new entrants cannot match. For instance, Google invested up to 28 times more than Yahoo in its general search engine (Figure 1). Arguably, Yahoo, which was the leading search engine in the early 2000s, faces and will likely face a hard time competing with Google because of the massive difference in investment capabilities.

Figure 1: Google and Yahoo, worldwide capital investments in general search, 2006-2015 ($ millions)

Source: Bruegel based on case AT.39740 Google Search (Shopping), para. 291, available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/39740/39740_14996_3.pdf.

These characteristics lead to situations in which only a few large online firms are the inevitable gateways to some digital markets, including online search engines, online networking services, operating systems and web browsers (Digital Competition Expert Panel, 2019). This situation does not necessarily mean dominance, but rather that the large firms are in a situation of significant intermediation power between end-users and business users. These characteristics thus lead to high barriers to entry that prevent current and potential competitors from easily entering digital markets.

Firm behaviour

Digital firms engage in different behaviour to entrench their power in a market, or to expand into new markets.

To entrench their positions in one market, firms often use commercial practices that maintain users on their service by imposing contractual clauses. For instance, they might impose price parity clauses that prevent their business users from offering better prices and conditions on other channels, including competing platforms and their own websites.

To expand into new markets, firms often promote their own services over rivals (self-preferencing), or provide their services jointly (tying).

Digital giants indulge in many other behaviours, but these are recurring behaviours that pose significant competition issues worldwide. They prevent competition (the protection of the competitive process) and fairness (balanced situations) in digital markets.

2.2 How authorities have responded

Antitrust investigations

The digital economy plays an essential role in the daily life of consumers and businesses. Competition authorities thus prioritise digital sector enforcement actions. Over the last decade, they have opened several antitrust investigations against the largest digital firms to tackle the behaviours outlined above. In Europe alone, 55 investigations have been opened. Some are ongoing or pending before courts (Carugati, 2022). An antitrust investigation requires an ex-post intervention after the practice takes place. Competition authorities need to follow specific steps to define a market, identify a dominant position in that market and identify an abuse of that dominant position, with a demonstration that anticompetitive effects outweigh procompetitive ones. Antitrust laws thus apply to dominant firms irrespective of the sector or market.

However, in the digital economy, these steps are often complex because of the characteristics of digital markets and the novelty of conduct. Therefore, competition authorities have had to develop new tools and legal approaches to building antitrust investigations. For instance, in Europe, the Google Search (Shopping) case (see Figure 1), confirmed by the European General Court (still pending before the European Court of Justice), took eight years and led to the development of new methods to define zero-price markets and the theory of self-preferencing[2].

Moreover, investigations take place on a case-by-case basis, while the issues they deal with are recurring. Investigations are also slow compared to the rapidity of change in digital markets. Even successful intervention might not restore the competitive process as the alleged anticompetitive practice sometimes leads to irreparable damage to competition that solutions in the form of remedies are unable to change. For instance, remedies to prevent Google from tying its Google Search service and Google Chrome browser to Google Android devices, following the European Google Android decision in 2018, confirmed by the European General Court (still pending before the European Court of Justice), did not change the competitive landscape in mobile search. Google's mobile search engine market share has not changed – it hovers at about 96 percent[3] – since the European Commission in 2018 ordered Google not to pre-install Google Search on Google Android devices[4].

New laws

The limitations of antitrust laws have led to several expert reports commissioned by governments, along with market investigations and contributions from competition authorities that show the need to adapt competition laws to the digital sector (Commission ‘Competition Law 4.0’, 2019; CMA, 2020a; Autorité de la Concurrence, 2020).

Policymakers in Europe, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States have responded by proposing new laws[5]. Laws in the United Kingdom (based on the UK proposal for a new pro-competition regime for digital markets; HM Government, 2021) and the US (the American Choice and Innovation Online Act and the Open App Markets Act) are under preparation or in the legislative process and not yet enacted. The Australian competition authority proposed recommendations similar to the UK proposal (ACCC, 2022). By contrast, the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA, Regulation (EU) 2022/1925) and section 19a of the German Competition Act are already in force[6]. Only Germany has started to enforce its new legislation by designating firms falling within the scope of the law and by opening or expanding existing antitrust investigations[7].

All laws have two phases: a designation phase and a compliance phase (OECD, 2022a, 2022b).

Designation phase

The designation phase aims to identify firms that will fall within the scope of the law. All the laws and draft laws we review target large online firms, active in the digital sector or some specific digital markets, ex-ante before the practice occurs. They use different terminologies and criteria, quantitative and qualitative or only qualitative, but target primarily the intermediation power of the largest digital firms: the GAFAM.

There is thus a shift from ex-post to ex-ante enforcement that targets only specific firms. The rationale behind this is to abandon the case-by-case approach to tackle recurring practices before they occur, and to speed up enforcement against the most important digital companies. Table 1 summarises the main elements of the designation phase.

Table 1: Main elements of the designation phase

|

|

Germany |

EU |

United Kingdom |

United States |

Australia |

|

Status |

In force |

In force |

Under preparation |

In the legislative process |

Recommendation |

|

Type of legislation |

Competition law with ex-ante rules |

Ex-ante regulation |

Ex-ante regulation (codes of conduct) |

Ex-ante regulation |

Ex-ante regulation (codes of conduct) |

|

Enforcer |

Competition authority |

Competition authority |

Competition authority |

Competition authority |

N/S |

|

Application |

Digital sector |

Some digital markets (eg online search engines) |

Some digital markets (to be defined) |

Some digital markets (eg operating systems) |

Some digital markets (to be defined) |

|

Terminology |

Firms with paramount significance for competition across markets |

Gatekeeper |

Firms with strategic market status |

Covered platforms |

Designated digital platforms |

|

Criteria |

Qualitative |

Quantitative and qualitative |

Quantitative and qualitative |

Quantitative and qualitative |

Quantitative and/or qualitative |

|

Designation process |

By the competition authority |

Notification by the firm and/or the competition authority |

By the competition authority |

By the competition authority |

By the regulator or minister |

|

Duration of the designation |

Five years |

Five years |

Five years |

Seven years |

N/S |

Source: Bruegel based on OECD (2022a, 2022b) and for Australia, ACCC (2022).

Compliance phase

During the compliance phase, competition authorities aim to ensure that in-scope firms respect the content of the laws. They impose a list of obligations and prohibitions (a rules-based approach), or a list of principles (a principles-based approach), with the goals of ensuring competitiveness or contestability and fairness. The lists vary between different laws and tackle both anticompetitive conduct and mergers.

In terms of anticompetitive conduct, laws focus on the same or very similar behaviours that govern the interaction between platforms and their business users (platform-to-business relationship) and end-users (platform-to-consumer relationship). The laws mainly prevent firms from engaging in unfair practices that restrict competition, including self-preferencing and tying. They also require firms to open up their services, products or assets to rivals, including by giving access to data or ensuring interoperability. In some instances, they also limit firms from using data in a certain way, as data is an important source of market power in the digital economy (Cabral et al, 2021)[8].

Despite similarities in tackling the same or very similar behaviours, the exact contents and scope of each obligation and prohibition in each law vary. For instance, in the EU, the DMA specifically requires interoperability between messaging services (Art. 7 DMA), whereas interoperability requirements in other laws do not specifically concern messaging services. Another example is the prohibition on combining data from different sources. In Europe, the DMA prohibits such combining of personal data unless the user has voluntarily given consent in line with the EU general data protection regulation (Art. 5(2) DMA), whereas in Germany, section 19a of the German Competition Act prohibits the processing of the data of end users and business users in the absence of sufficient choice in relation to processing (Art. 19a(2)(4) GWB). Therefore, while laws target the same practice, the requirements differ. As outlined in section 3, this might prevent jurisdictions from treating digital markets consistently.

Apart from in the EU, firms can show that a practice is necessary because objective justifications demonstrate positive effects that outweigh negative effects on the market. In other words, laws mainly stick to the effect-based approach instead of the object-based approach of per-se rules. The latter is rigid and leads to quick enforcement that might give rise to over-enforcement (type I errors) and punish conduct that is not anticompetitive. By contrast, the former is flexible, but enforcement is slower in a way that reduces type I errors because of the exchange between competition authorities and firms. Nevertheless, the object-based approach of the EU legislation allows for some flexibility. As the sole enforcer of the DMA, the European Commission can specify some rules and even provide guidance on how firms should comply with them. By contrast, the effect-based approach allows for speedy enforcement by presuming that the conduct is anticompetitive unless the firms supply evidence of positive effects.

In mergers, some laws introduce an obligation to report all intended acquisitions to the competition authority in view of a merger review. The rationale is to catch more mergers after years of under-enforcement (type II errors), as most acquisitions by the largest digital platforms have not exceeded merger control thresholds because of the low or non-existent turnover of the acquired firm (the target) (Digital Competition Expert Panel, 2019). The goal of the obligation is thus to identify mergers that would require the merging parties to notify the acquisition for an ex-ante authorisation by the competition authority because they are likely to pose competition issues. Some laws even require the merging parties to notify the acquisitions to the competition authority.

Finally, in case of non-compliance, laws allow sanctions in the form of fines to be imposed. Authorities can also impose remedies that can change a firm’s behaviour, such as by setting interoperability requirements (behavioural remedies), or its structure, such as by imposing ownership separation (structural remedies). Some laws even allow the enforcer to prohibit mergers and remove senior managers. Table 2 summarises the main elements of the compliance phase, bearing in mind that the exact contents of each obligation and prohibition differ between laws. Therefore, Table 2 is a high-level comparison for a general understanding of the compliance phase, and not a granular comparison between laws, as provided by the OECD (2022a, 2022b).

Table 2: Main elements of the compliance phase

|

|

Germany |

Europe |

United Kingdom |

United States |

Australia |

|

Type of approach |

Rules-based and effect-based |

Rules-based and object-based |

Principles-based and effect-based |

Rules-based and effect-based |

Principles-based and effect-based |

|

List of don'ts |

|

||||

|

Self-preferencing |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Unfair terms and conditions |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Tying/bundling |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Anti-steering strategies |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Lock-in strategies (eg uninstall software) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Combine data from different sources |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Use of non-public data |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

List of dos |

|

||||

|

Data access |

Yes (private enforcement) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Interoperability |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Portability |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Data silos |

Yes |

Yes (if systematic infringement) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Open standard |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Data sandboxes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Data trustees |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Short data retention periods |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Mergers |

No specific rules (but the competition authority can mandate notification after a sector inquiry) |

Mandatory information of all intended acquisitions in the digital sector |

Mandatory notification of acquisitions that meet quantitative and qualitative criteria |

No specific rules |

No |

|

Sanctions |

Fine |

Fine |

Fine (firm and senior managers) |

Fine |

Fine |

|

Remedies |

|

||||

|

Behavioural and structural |

Yes (structural only if behavioural remedies are ineffective) |

Yes |

Yes (structural only if behavioural remedies are ineffective) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Prohibition of mergers |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Director removal |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Source: Bruegel based on OECD (2022a, 2022b) and for Australia, ACCC (2022). Note: Anti-steering strategies can include price parity clauses that prevent their business users from offering better prices and conditions on other channels. Data silos refers to the separation of data to prevent the use of data collected for one purpose being used for another. Data sandboxes refers to the testing of the practice by firms in a controlled environment. Data trustees are independent intermediaries between data providers and data users to ensure correct handling of sensitive data.

3 The solution

3.1 Rationale

There is a need to ensure interoperability between different competition laws to achieve consistency in the treatment of digital markets for two main reasons.

First, the digital economy is often borderless. Digital firms often provide the same products and services and implement the same commercial practices globally. At the same time, they must comply with several national and supranational laws that impose different requirements. This increases compliance costs and generates risks of inconsistency. For instance, in the EU, gatekeepers under the DMA cannot impose unfair terms and conditions. However, some EU laws, such as the Platform to Business (P2B) Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/1150), and national laws, such as the French restrictive practices law, already impose fairness requirements in terms and conditions. The interpretation of fairness might be different between laws and jurisdictions. Thus, there is a risk that terms and conditions that are fair in one country are unfair in another, obliging digital firms to adapt their terms and conditions nationally, whereas they should ideally be the same globally because of their borderless nature. Interoperability enables different laws to be compatible to reduce compliance costs for businesses and so firms can more easily scale up across borders.

Second, the digital economy often involves the same competition issues worldwide. Competition authorities thus investigate the same or very similar issues, but they take different approaches and work at different speeds because the particularity of each national law. Jurisdictions sometimes duplicate human resources and time on similar investigations that might lead to different outcomes because of the different approaches taken and varying interpretations of the law, thus increasing inconsistency. For instance, competition authorities in France, Italy and Sweden found in the 2015 online hotel booking case that wide price parity clauses that prevent better prices and conditions being offered via any retailer are illegal, but narrow clauses that restrict offers only on the supplier’s own website are legal[9]. By contrast, in the same case, the German competition authority found that both clauses are illegal[10] (Bundeskartellamt, 2015). Interoperability enables competition authorities to apply the same legal interpretation.

3.2 Methodology

The purpose of interoperability is to ensure that different laws work together. The goal is thus to offer a framework for current and future antitrust and digital competition laws. The framework relies on four non-binding elements. They are non-binding to spur adoption without policy and legal constraints.

First, the adoption of a common phases. The previous section shows that implementation of laws follow two phases: phase 1 is the designation of firms, and phase 2 is the imposition of compliance measures. In phase 1, the laws adopt different terminologies and criteria to encompass a narrow set of firms, such as only some firms in some digital markets, or a border set, such as firms in the digital sector irrespective of a particular digital market. Overall however, it is the largest digital firms that are targeted to tackle competition issues in the digital sector. In phase 2, the laws adopt different approaches but tackle the same or very similar practices with lists of obligations and prohibitions. Countries preparing digital competition legislation should follow a similar two-phase approach to ensure clarity.

Second, the adoption of a common interpretation. The content of each law is subject to interpretation by the enforcer and courts. This is where inconsistency is likely to arise. Competition authorities and judges worldwide are likely to interpret laws differently and impose different requirements on firms. This will likely lead to inconsistency and incompatibility of laws. The worst outcome would be incompatible requirements. For instance, the hotel booking cases mentioned in sub-section 3.1 show that some countries allow a practice that is not allowed in another. Adopting a common interpretation through guidance on the assessment of obligations and prohibitions defined in international forums, such as the International Competition Network (ICN), which brings together 140 competition authorities from 130 jurisdictions, will ensure consistency between laws.

Third, the adoption of common technical requirements. While the interpretation is the theory, the technical implementation is the practice. Most practices in the digital economy involve complex technical issues related to data, algorithms and user interfaces that nudge users to act in certain ways. Competition authorities (especially their digital economy units) should work with stakeholders, including the firms concerned by the rules, and with civil society organisations, on how digital firms should implement the rules in the context of technical workshops organised by international forums, such as the ICN.

Fourth, the implementation of an international monitoring committee. The implementation of the rules should be effective. Therefore, competition authorities should monitor that they effectively and consistently implement the rules, and if not, quickly solve any inconsistency. They should do so by creating a monitoring committee within the ICN.

3.3 Limitations

The methodology has some important limitations that might impact its effectiveness in practice.

First, limitations regarding the non-binding nature of the above measures. In practice, competition authorities and judges can depart from them. They might have incentives to do for multiple reasons. These include different facts, national situations that impact national actors, legal precedents or policy objectives (eg privacy, promoting national champions, protecting national actors). It follows that countries might have different interests, thus resulting in different outcomes and potential inconsistency.

Second, limitations regarding the scope of the above measures. The measures aim to harmonise the interpretation and technical implementation of antitrust laws and digital competition laws. Other national laws, such as civil laws or restrictive practices, that might also apply to practices by large digital firms, would fall outside the scope. Courts are most of the time in charge of applying these national laws. They must rule based on the context, facts and legal precedents. It follows that applying national laws might lead to different interpretations and outcomes. Furthermore, Courts do not have national or international networks that would enable them to ensure consistency.

Nevertheless, these limitations do not mean that the framework would be compromised. Enforcement authorities are likely to overcome the first limitation as they have called for several years for international cooperation in competition for digital markets (G7, 2019). Departing from a framework that would ensure consistency is thus not in line with previous statements. Enforcement authorities are likely to overcome the second limitation by raising judges’ awareness of the importance of ensuring consistency in digital markets, notably by requiring national courts dealing with competition issues in digital markets to share with the ICN public versions of their judgments.

References

ACCC (2022) Digital platform services inquiry, Interim report No. 5 – Regulatory reform, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, available at https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Digital%20platform%20services%20inquiry%20-%20September%202022%20interim%20report.pdf

Autorité de la Concurrence (2020) ‘The Autorité de la concurrence’s contribution to the debate on competition policy and digital challenges’, 19 February, available at https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/sites/default/files/2020-03/2020.03.02_contribution_adlc_enjeux_numeriques_vf_en.pdf

Cabral, L., J. Haucap, G. Parker, G. Petropoulos, T. Valletti and M. Van Alstyne (2021) The EU Digital Markets Act, A Report from a Panel of Economic Experts, European Commission Joint Research Centre, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Carugati, C. (2022) ‘How the European Union can best apply the Digital Markets Act’, Bruegel Blog, 4 October, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/how-european-union-can-best-apply-digital-markets-act

CMA (2020a) Online platforms and digital advertising, Market study final report, Competition and Markets Authority, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5fa557668fa8f5788db46efc/Final_report_Digital_ALT_TEXT.pdf

CMA (2020b) A New Pro-Competition Regime for Digital Markets. Advice of the Digital Markets Taskforce, Competition and Markets Authority, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5fce7567e90e07562f98286c/Digital_Taskforce_-_Advice.pdf

Commission ‘Competition Law 4.0’ (2019) A new competition framework for the digital economy, Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi), available at https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Wirtschaft/a-new-competition-framework-for-the-digital-economy.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3

Crémer, J., Y.-A. De Montjoye and H. Schweitzer (2019) Competition policy for the digital era, European Commission, Directorate-General for Competition

Digital Competition Expert Panel (2019) Unlocking digital competition, HM Treasury, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

European Commission (2020) ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act)’, COM/2020/842 final

G7 (2019) ‘Common Understanding of G7 Competition Authorities on “Competition and the Digital Economy”’, G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 5 June, available at https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/sites/default/files/2019-07/g7_common_understanding.pdf

HM Government (2021) A new pro-competition regime for digital markets, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1003913/Digital_Competition_Consultation_v2.pdf

OECD (2022a) Analytical note on the G7 inventory of new rules for digital markets, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://www.oecd.org/competition/analytical-note-on-the-g7-inventory-of-new-rules-for-digital-markets.pdf

OECD (2022b) G7 inventory of new rules for digital markets, OECD submission to the G7 Joint Competition Policy Makers and Enforcers Summit, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://www.oecd.org/competition/g7-inventory-of-new-rules-for-digital-markets-2022.pdf

OECD and ICN (2021) OECD/ICN Report on International Co-Operation in Competition Enforcement, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Competition Network, available at https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/OECD-ICN-Report-on-International-Co-operation-in-Competition-Enforcement.pdf

Footnotes

[1] See Bundeskartellamt press release of 12 October 2022: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/12_10_2022_G7.html.

[2] See European Commission press release of 27 June 2017: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1784, and General Court of the EU press release of 10 November 2021: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-11/cp210197en.pdf.

[3] Including Google Android and Apple devices; source https://statcounter.com/.

[4] See European Commission press release of 18 July 2018: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4581, and General Court of the EU press release of 14 September 2022: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2022-09/cp220147en.pdf.

[5] See European Commission, 2020; CMA, 2020b. See also Bundeskartellamt press release of 19 January 2021: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2021/19_01_2021_GWB%20Novelle.html?nn=3591568, and David N. Cicilline press release of 24 June 2021: https://cicilline.house.gov/press-release/cicilline-statement-on-big-tech-markup. Legislative proposals were also introduced in Greece and Italy, but subsequently dropped. In South Korea, a law requires app stores to allow alternative payments. In Japan, a law imposes fairness and transparency requirements on some large firms, rather than a list of dos and don’ts to tackle anticompetitive behaviour. We thus exclude Japan from our analysis of new laws. In the United States, more than 15 relevant bills were introduced in 2021 and 2022. At time of writing, the most advanced with the highest likelihood of being adopted are the American Choice and Innovation Online Act and the Open App Markets Act. In referring to the US, we focus on these two bills. Other countries, including Turkey, Canada, Australia and India, are considering legislation but have not yet made proposals.

[6] Amendment of the German Act against Restraints of Competition, 18 January 2021; see Bundeskartellamt press release of 19 January 2021, https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2021/19_01_2021_GWB%20Novelle.html?nn=3591568.

[7] See Bundeskartellamt press release of 6 July 2022: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/06_07_2022_Amazon.html.

[8] In Germany, section 18(3)(3) of the German Competition Act clearly states that data is a source of market power.

[9] Autorité de la concurrence press release of 23 April 2015: https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/en/communiques-de-presse/21-april-2015-online-hotel-booking-sector.

[10] Bundeskartellamt press release of 23 December 2015: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2015/23_12_2015_Booking.com.html.