How well does China’s reopening bode for the economy? A political economy story

China’s zero-Covid policy was an unsustainable economic model and yet the announcement to reopen the economy came as a surprise to the world. Even more unexpected was its rapid – if not immediate – implementation.

It should have been clear when the Omicron variant reached China in January 2022 that Covid-19 could and would spread despite a zero-Covid policy. The irony of this, however, is that China’s leadership decided to maintain its stance for as long as eleven months afterwards. Even during the 20th Party Congress in October, no sign was given that zero-Covid policies would be lifted.

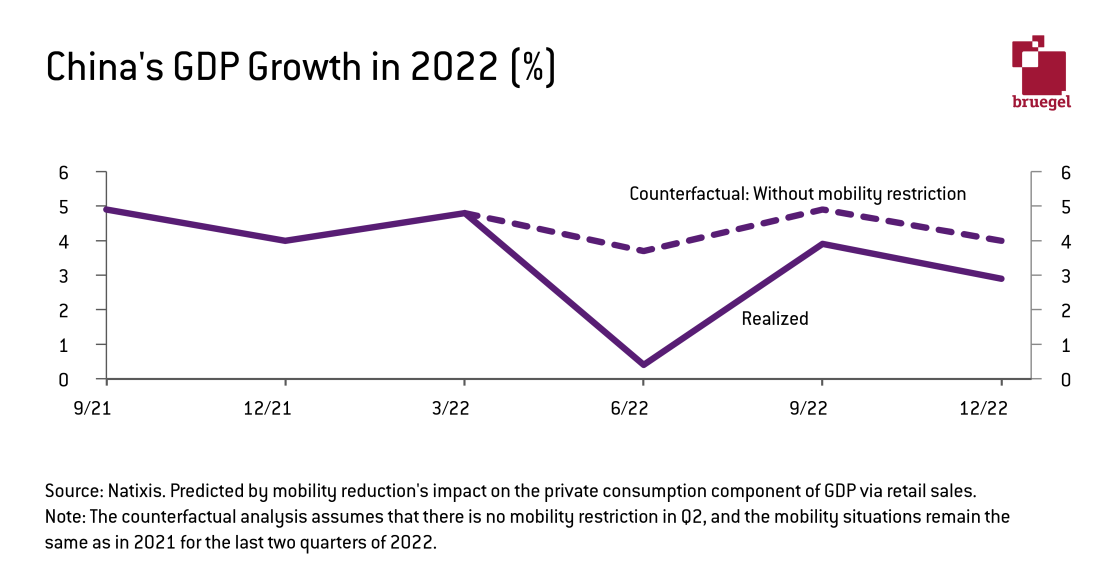

The effects of the China’s Covid strategy were seen in various ways. Tight mobility restrictions had negative impacts on activity in China and the reduction in consumption alone reduced GDP growth by as much as 2.5% in 2022. As a result, the actual GDP growth rate of China ended up only being 3% last year. If mobility restrictions had not been implemented, GDP growth could have been as high as the official target of 5.5%.

A recovery in consumption has occurred since mobility restrictions were lifted at a national level in December. Pre-Covid levels are nearly restored and this was demonstrated by inter-city travel rising quicker than intra-city mobility in the run up to the Chinese New Year.

Two other important policy measures which damaged GDP growth were a further tightening of real estate restrictions and a crackdown on the tech and the general private sector. Both of these caused a collapse in investment and while China’s reopening will certainly throw a lifeline to both in terms of demand for housing and tech sectors, this is not the main reaon why the outlook for both sectors has improved, at least in the short term.

In fact it is really about the political economy of China and where its political regime stands today. The increasingly poor economic situation since the US-led trade war started, along with the Covid-19 crisis and the demise of real estate and tech sectors make it absolutely essential for the leadership to restart the economy. Given the poor state of local government finances, the collapse of many SMEs, the stagnant households income and the growing youth unemployment, this is a non-negotiable objective.

China’s growth trajectory is certainly heading back on track. This is not only the reason why the reopening from zero-Covid policies has happened at lightning speed but also why the government is lifting regulatory restrictions on real estate developers and much of the pressure on the tech sector. The well-known ‘three red lines’ policy for real estate developers to limit leverage has been lifted and tech companies are ready to jump on new IPOs and other ventures. Both sectors are bound to be better placed in 2023 than last year given the importance of growth in the political agenda.

I expect growth to hover around 5.5% in 2023, which is slightly above the latest IMF projection in the Spring World Economic Outlook (forecasted at 5.2%) but still less than some sell-side analysts. The bulk of China’s growth should come from the recovery of consumption, followed by some recovery in investment as sentiment improves. External demand should contribute less to China’s growth in 2023, especially in the first half, given stagnant growth in the US and Europe.

Challenges beyond 2023

While there will be less pressure on the private sector in 2023 in order to boost household income, the government is unlikely to implement a complete U-turn on policies designed to rein in the private sector. As long as the Xi Jinping administration remains convinced of the superiority of China’s economic model – which is tightly linked to the political model – there will not be a structural change.

The support for the private sector, including real estate developers and tech companies, is back now because there is a lack of a better option. Chinese leaders desperately need growth to be reset. Once this tactical objective is achieved, the leadership will be expecting both the real estate and the tech sectors to contribute to the China dream by supporting common prosperity. Furthermore, tech entrepreneurs, the core of the private sector, will probably need to continue to be monitored to ensure they remain aligned with the party’s strategy and objectives.

Even if political tensions remain high, 2023 should be a good year for China’s growth outlook at least when compared to what is expected down the line. 2023 will be cyclically good but, structurally, China’s growth will continue to decelerate. The explanation for this much more positive path for 2023 is simple: it’s because of the large and positive base effect after the terrible 2022. In 2024, however, the base effect will be negative, and will curve out growth up to 4.5%. Structurally for the next few years, it will reduce to around 2.5% by 2030.

China’s leadership will need to deliver growth to improve the currently difficult economic conditions of local governments, SMEs and households. This will be easy in 2023 but much harder in future.

ZhōngHuá Mundus is a newsletter by Bruegel, bringing you monthly analysis of China in the world, as seen from Europe.

This is an output of China Horizons, Bruegel's contribution in the project Dealing with a resurgent China (DWARC). This project has received funding from the European Union’s HORIZON Research and Innovation Actions under grant agreement No. 101061700.