The Belt and Road Initiative transformation makes it a more – not less- useful tool for China

When President Xi announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Kazakhstan in 2013, it attracted much speculation across the globe. Shrouded in nebulous historical analogies and proverbs, many thought of the BRI as a mere diplomatic trick. However, Chinese overseas lending – already on the rise since the mid-2000s – grew exponentially under the mantra of this grand initiative.

The official objective for BRI, as shown in the 2015 State Council’s ‘Vision and actions on jointly building Belt and Road’ plan, was to improve connectivity in three areas. First, trade and investment, with transport infrastructure as a key enabler. Second, people-to-people connectivity, which was supported by the development of the relevant infrastructure (i.e. institutional partnerships to facilitate cultural exchanges). Finally, financial cooperation that would enable the financing of huge infrastructure needs stemming from the BRI.

Since 2015, many developments in China have changed how people, especially Western scholars, view the BRI. Because of the US-China trade war, the US containment of China’s technological rise and China’s much more belligerent approach to the West, many now see the BRI as a way for China to expand its influence in the rest of the world. China’s key objectives have changed since President Xi rose to power. China has made the US its main rival, shifting away from the collaborative relationship under previous Chinese leaders such as Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

The US has also relabelled its relationship with China from one of engagement and cooperation to one of competition and rivalry. The worsening relations between China and the US are damaging the image of the BRI globally. It is still positively received in Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, even if its reputation has deteriorated rapidly in the former. The perception of the BRI in Europe and North America was one of doubt to begin with and has only worsened since. The deteriorating image of the BRI possibly made the Chinese government question the feasibility of such a grand plan, which most likely explains the recent shift in the direction of China’s policy.

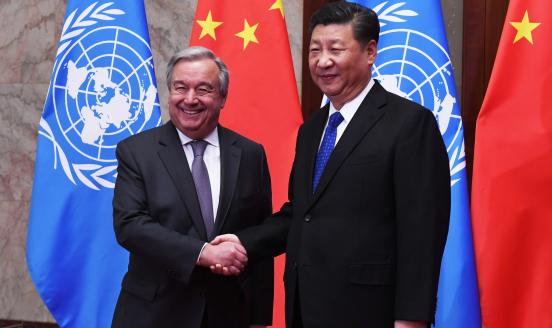

Since 2021, new ideas such as the ‘Community with a shared future for mankind’, the ‘Global Development Initiative’ and the ‘Global Security initiative’ started to seep into President Xi’s speeches. The ‘Community with a shared future for mankind’ initiative was popularised by President Xi at the WEF in Davos in 2017 and inserted into several United Nations General Assembly resolutions since the 72nd Session. It is an overarching umbrella for China’s international relations with a strong emphasis on win-win outcomes and a multipolar world order. The ‘Global Development Initiative’ was introduced by Xi Jinping at the UN General Assembly in 2021 as a China-led initiative to advance the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 agenda. Finally, the ‘Global Security Initiative’ was introduced in April 2022, just one month after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, focusing on state sovereignty.

The above concepts appear frequently in Chinese media. As a result, some commentators in the West would have you believe that the BRI is dead, but this is not true. President Xi continues to talk extensively about the BRI and it seems the Chinese government is using those initiatives to complement the existing BRI framework, not to replace it. Moreover, the ‘Global Development Initiative’ and ‘Global Security Initiative’ are embedded in a multilateral discourse that perfectly resonates with UN development discourse. China is elevating the BRI to a vehicle for its UN engagement. The BRI has transformed from being solely an economic strategy to one with a much broader political and security-focused scope.

The BRI is no longer just about infrastructure and connectivity but has evolved into a more security-oriented concept centred on an alliance of the Global South with a clear anti-Western tone. It serves as one of several devices uniting the Global South in a new and comprehensive narrative. Beyond the BRI, this new narrative features cooperation in the fields of digital governance, as well as academic and cultural exchanges. This does not mean that China’s role in building infrastructure overseas will wane but rather that it will be more driven by political synergies.

China is more prepared than ever to leverage its economic size to reach political and security alliances. This will have an important bearing for the EU’s response to the ever-increasing Chinese engagement with the developing world, namely in the context of the EU Global Gateway Strategy. The Global Gateway seems essentially economic in nature and developmental in design. The question is whether this focus remains appropriate or is by now too narrow, given China’s broadening scope for the BRI and other narratives.

ZhōngHuá Mundus is a newsletter by Bruegel, bringing you monthly analysis of China in the world, as seen from Europe.

This is an output of China Horizons, Bruegel's contribution in the project Dealing with a resurgent China (DWARC). This project has received funding from the European Union’s HORIZON Research and Innovation Actions under grant agreement No. 101061700.