China’s new regulator hints at a major clean-up of the world’s largest financial sector

Among several institutional changes, the most significant might be the creation of a new nationwide regulator to oversee China’s financial industry.

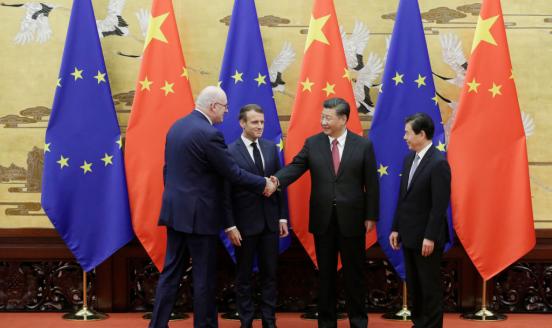

China’s 2023 National People’s Congress, which concluded on 13 March, was mainly significant for its confirmation of Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third term as president, which comes on top of two other roles he was confirmed in at the Twentieth Party Congress in November 2022: Party Secretary and head of the People’s Liberation Army. Not even Chairman Mao managed to keep these three leading positions for three terms.

In this context, it might have been easy to miss other announcements of centralisation of power in the economic and financial spheres. Among several institutional changes, the most significant might be the creation of a new nationwide regulator to oversee all parts of China’s financial industry. This new regulator will take over responsibility for financial consumer protection and day-to-day supervision of financial holding companies from the People’s Bank of China, and investor protection from the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

The announcement of this centralised agency deserves attention for a number of reasons. First, China’s financial sector is now the largest in the world, with $60 trillion in assets, equating to 340% of GDP. Chinese banks also top the list of the largest globally systemic financial institutions, which increasing interrelationships with the rest of the global financial system. Chinese banks, especially development banks, were lending abroad massively until recently, when they stopped lending, with major consequences for the Global South. In that context, any action that affects China’s financial sector is important for China and for the rest of the world.

Second, the concentration of regulatory and supervisory power in fewer hands comes with little clarity, so far, on reporting lines and the role of Xi Jinping in overseeing this regulator. The rumours are that the salaries of civil servants in existing regulatory agencies will be reduced. Meanwhile, a major restructuring of central government personnel is taking place, with an overall 5% cut. A plausible reason for cutting the salaries and number of civil servants is to create the necessary fiscal space to populate the new financial institution.

Creating a new institution at a time when the Chinese economy is struggling to recover from the scarring left by COVID-19 and zero-COVID-19 policies might seem like too much of a luxury. But this might not actually be the case in a particular circumstance of a potential financial crisis in China, which would need to be tackled swiftly and effectively. The international evidence shows that centralised regulatory and supervisory agencies tend to be created when systemic risk is high and a potential restructuring of the financial system is warranted. The question, therefore, is whether China finds itself in this situation today.

Three factors suggest it might. First, systemic risk stemming from a much more complex financial sector with very large off-balance-sheet positions remains pervasive, notwithstanding President Xi’s announcement in 2017 of a “crusade” against the shadow banking. In fact, since then, China’s overall debt has increased.

Second, the collapse of a number of real-estate developers, which started in the second half of 2021 and continued until very recently, has harmed financial institutions. The weakening of the sector is not fully over.

Finally, local governments have had to shoulder most of the expenses related to zero-COVID-19 policies, while seeing revenues plummet from their major income generator – land sales. By the third quarter of 2022, all provinces in China were running fiscal deficits and had to be supported by the central government.

Concentrating regulatory and supervisory powers in a small but agile and high-level agency with direct access to the State Council, and possibly also to Xi Jinping directly, should make coordination much easier and, most importantly, faster at times of potential financial distress. Another advantage of this agency could be that it is easier to link any potential decision to restructure a particular financial institution with the sources of funding to finance these actions. A good example of this was China’s restructuring of its largest banks in the early 2000s, for which foreign reserves were use as funding pool to recapitalise these banks.

The creation of this centralised regulatory and supervisory agency may be almost as important a piece of news as Xi Jinping’s third term, if it implies the Chinese government is getting ready for a major clean-up of its financial sector, which has ballooned in terms of size and influence on the rest of the world.