US Tariffs Aim to Contain China’s Technological Rise

While tension increases with each of the imports listed under the new tariffs, it now seems clear that the US are trying to slow down China's technolo

This opinion piece has been published in Caixin

Beijing’s attempts to calm down a furious U.S. administration (with promises of opening up sectors and a stronger yuan) do not seem to have convinced the White House to tone down its protectionist actions against China. Following two rounds of import tariff hikes earlier this year, the U.S. announced a 25% hike in import tariffs on 1,333 products exported from China to the U.S. at an estimated value of $60 billion.

The given reason for this third round of measures is no longer national security (for tariffs on steel and aluminum) or safeguarding domestic industries (for solar panels and washing machines), but rather, China’s breach of intellectual property rights. In only a few hours China has stepped up its retaliation from a small package ($3 billion) targeting a few agriculture-related products to a much larger list of 106 products valued approximately $50 billion. More importantly, China’s targeted products are no longer low-end but include higher-end products, such as aircraft and automobiles.

We argue that the U.S. strategy has evolved over time from one in which the purpose was to reduce the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China to a much more targeted but also relevant one, namely constraining China’s progress up the industrial ladder. This is evident from the fact that the U.S. has excluded most of its allies from the import tariff hikes on steel and aluminum and targeted only China with the most recent measures to protect U.S. manufacturers’ intellectual property rights.

More importantly, out of the 1,333 targeted products, around 70% of them (by count) are high-end manufactures. In other words, the U.S. administration’s latest move has hit China where it hurts the most, namely its goal to upgrade its manufacturing industry, a key strategic plan called Made in China 2025. In turn, only 3% of the import products included in the U.S. list, are low-end products, which further supports our thesis of the U.S.’ final goal: containing China’s technological rise.

As for China’s reaction, it has clearly moved from shyness to aggressiveness ($3 billion towards $50 billion) and covered a very different set of products. A careful analysis of China’s imports from the U.S. by product can help us explain the reasons behind such behavior and, ultimately, the costs involved.

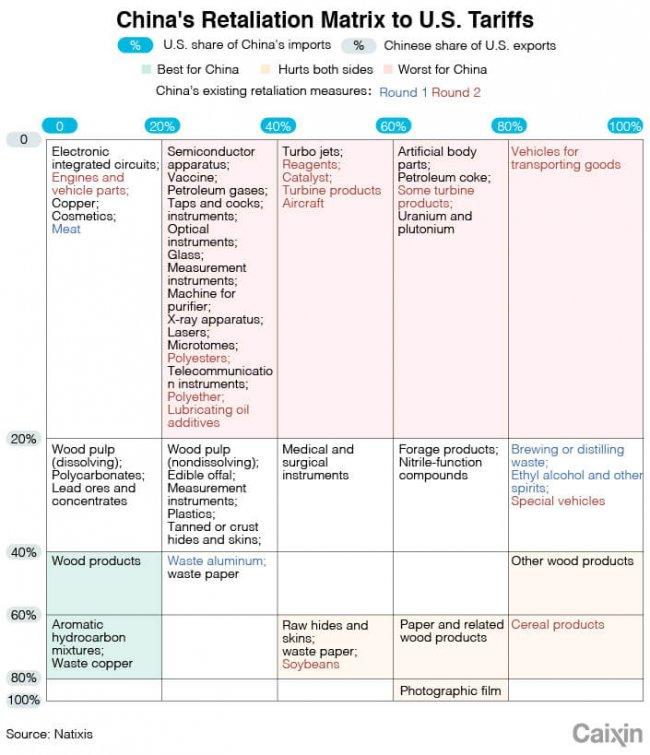

We argue that an effective retaliation by China should include products complying with two key conditions: First, China should be a large enough market for a specific U.S. export product so real harm could be inflicted on U.S. exporters in that specific sector. Second, the U.S. should not be China’s main sourcing country for that specific product. The reality is that only a few products, namely wood, aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures and waste copper, comply with these two criteria. In other words, China’s ability to execute a painless retaliation is very limited in terms of potential products. As the table below covering the universe of China’s exports to the U.S. shows, China’s first $3 billion package was quite aligned with the idea of a painless retaliation (see products marked in blue in aforementioned table) but this is no longer true for the second, larger set of targeted imports from the U.S. (products marked in red in the same table).

This is understandable as the U.S.’s intentions became clearer with the 1,333 product list. The U.S.’ attempt to contain China’s technological rise by limiting China’s exports of higher-end products has obliged China to raise the stakes and retaliate in a much more painful way, namely targeting higher-end imports from the U.S. While this may take a toll on the speed of China’s technological catch-up, it will all depend on whether other developed countries follow the U.S. in its protectionist move. In that regard, not only trade relations between China and the European Union are all the more relevant in this context, but also China’s relationships with Japan and South Korea.