China is the world's new science and technology powerhouse

Chinese R&D investment has grown remarkably over the past two decades. It is now the second-largest performer in terms of R&D spending, on a country b

This piece was originally published in BRINK Asia.

Scientific knowledge and its use in technology and economic and societal development has become increasingly global and multipolar. While Europe and the U.S. have traditionally led in scientific development, China in particular has emerged as a new science and technology (S&T) powerhouse.

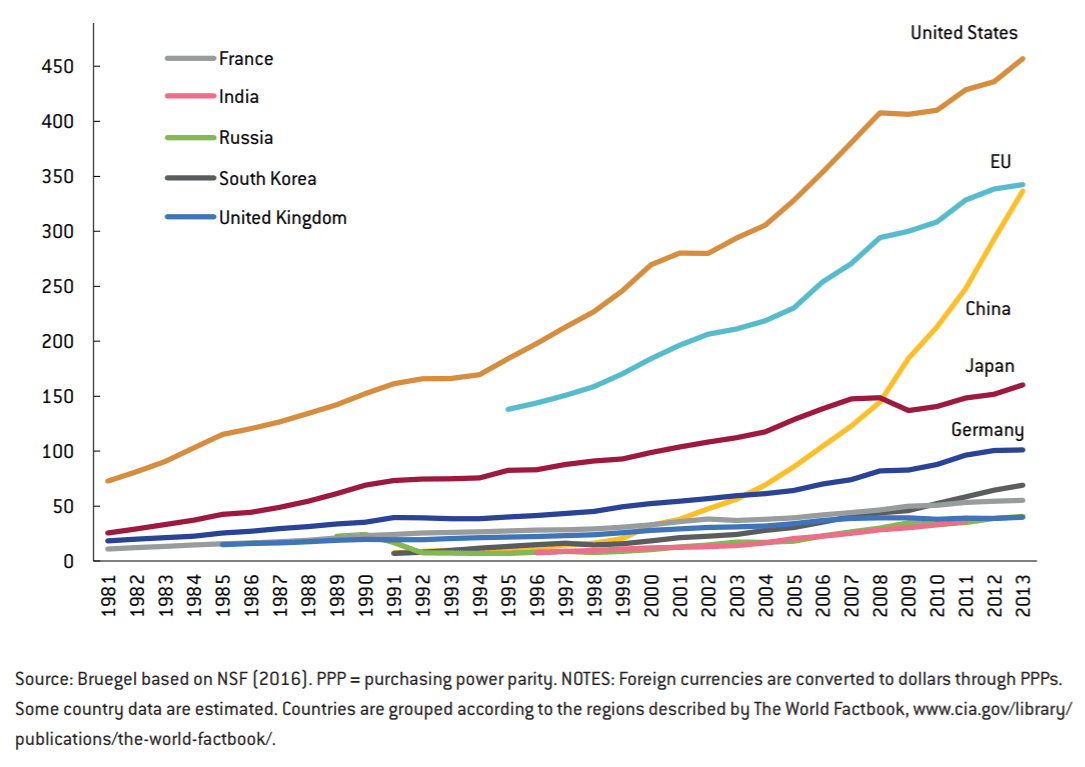

A key indicator of the rise of China in S&T is its spending on research and development (R&D). Chinese R&D investment has grown remarkably over the past two decades, with the rate of growth greatly exceeding that of the U.S. and the EU.

China is now the second-largest performer in terms of R&D spending, on a country basis, and accounts for 20 percent of total world R&D expenditure. It is also increasingly prominent in industries that intensively use scientific and technological knowledge.

Exhibit 1: R&D spending in billions of dollars (current, in purchasing power parity terms)

While the U.S. has led the world in the production of scientific knowledge for decades, in terms of both quantity and quality, and the EU as a bloc (still including the UK) has outperformed the U.S. in numbers of scientific publications since 1994, China now publishes more than any other country apart from the U.S. China’s scientific priorities are shown by a particularly big increase in its share of published papers in the fields of computer sciences and engineering. While China—for now—is making modest inroads into the top-quality segment of publications, it is already on par with Japan.

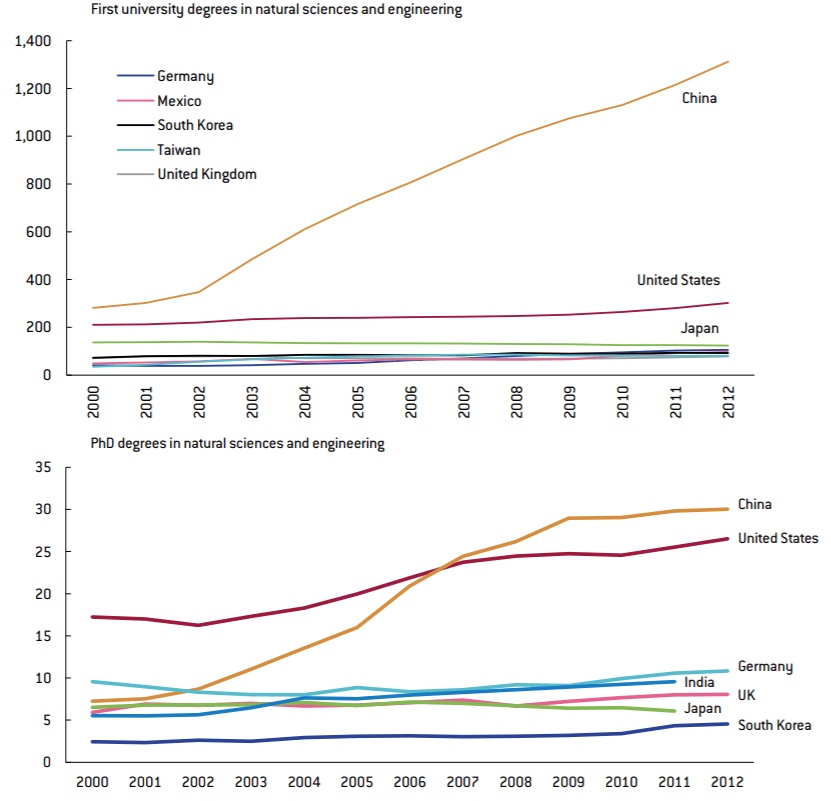

This steep improvement in S&T performance has been underpinned by significant strides in science and engineering education. China is now the world’s number one producer of undergraduates with science and engineering degrees, delivering almost one quarter of first university degrees in science and engineering globally. Since 2007, the country has awarded more Ph.D. degrees in natural sciences and engineering than any other country globally.

Exhibit 2: The growing number of degrees awarded (in thousands)

Source: Bruegel, based on NSF (2016)

China’s rise in science and technology is not an accident. Successive Chinese leaderships have seen S&T as integral to economic growth and have consequently taken steps to develop the country’s S&T-related infrastructure.

Technology development and innovation figure prominently in the current thirteenth five-year plan (2016-20). China’s National Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology Development (MLP), introduced in 2006, is an ambitious plan to transform the Chinese economy into a major center of innovation by the year 2020 and to make it the global leader in science and innovation by 2050. One of the goals of the MLP is to boost R&D expenditure to 2.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP)—a target that has largely already been reached.

Global Implications

The benefits from a global science world with China as an extra strong pole will accrue to many, but some will benefit more than others. In particular, the EU and the U.S. will likely respond in different ways to the rise of China as an S&T powerhouse.

The U.S. science system has traditionally benefited from foreigners. The dominant position of the U.S. in science is based on its openness to the brightest talent of all nationalities, and this top position keeps attracting the best talents from around the world, who contribute to U.S. science, technology and economic success. Foreign talent is thus vital for U.S. science and engineering capacity. This is why the U.S. could feel threatened about the fact that the power of its S&T machine will diminish if the pool of foreign talent entering the U.S. dries up. There is no clear evidence so far, however, to justify this fear.

For the moment, the rise of China’s own capacity to produce science and engineering degrees does not seem to disconnect the U.S. from the pool of potential Chinese candidates to recruit from. With continued high attrition rates in China and high stay rates in the U.S. for foreign scientists, this open model, at least for the moment, continues to bear fruit for the U.S., even if the most important source country, China, is rapidly developing its own scientific capability.

China’s growth model for science, although aspiring to be indigenous, still involves sending out its increasingly better locally trained scholars to the best institutes in the world and reaping the benefits upon their return in later stages of their careers when they have fully developed their capabilities. All this leaves a China-U.S. connection that is virtuous, mutually beneficial for both science systems, and so far robust.

Nevertheless, concerns are mounting in the U.S. about the sustainability of its capacity for innovation and international competitiveness, driven by the more recent trend to move to a more restrictive immigration policy. This comes in addition to a reluctance to allocate public funding to support the building of S&T infrastructure.

The EU science pole is largely holding its own, based on the intensifying process of intra-EU integration. However, this process of integration is bumpy, and with the Brexit vote outcome, it is facing a major challenge. Furthermore, the EU S&T pole does not have the same deep openness to foreign scientific talent from China that the U.S. has, resulting in the absence of similarly sized flows of students and researchers.

The EU must show a stronger commitment to joining the science globalization train and subsequently ensure that European economies will benefit from it. An integrated European area for science and technology, characterized by scientific and technological excellence, is a necessary condition for this. Excellence will ensure that talented people in European research institutes and firms will be better able to absorb the new knowledge generated abroad and will be more attractive hubs for the best talent from abroad and for partners for international S&T cooperation and networks. But while reinforcing the European pole by deeper integration, it should also be more open externally.

The intra-EU mobility agenda should avoid navel gazing and be seen more as a lever for global integration. European S&T policymakers should promote and remove barriers for scientific collaboration both intra-EU and with countries outside the bloc. It should do more to attract the best foreign talent, wherever it is located in the world.

Mutual Benefit

China’s ambition to be a global leader in science and innovation by 2050 seems well within reach. The U.S. remains the favored destination for Chinese students, which has led to the creation of U.S.-China science and technology networks and connections that are mutually beneficial, enabling China to catch up and helping the U.S. to keep its position at the science frontier. The EU has much less-developed scientific connections to China than the U.S. The EU should take steps to engage more with China if it is not to miss out in the future multipolar science and technology world.

A more detailed analysis can be found here. All data in the article is from the same policy paper.