Yields on the rise

US government bond yields have increased recently, mainly due to the talks about tapering the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) programme. Th

US government bond yields have increased recently, mainly due to the talks about tapering the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) programme. This has prompted yield increases in a number of other countries. Yields are also expected to increase further: by how much?

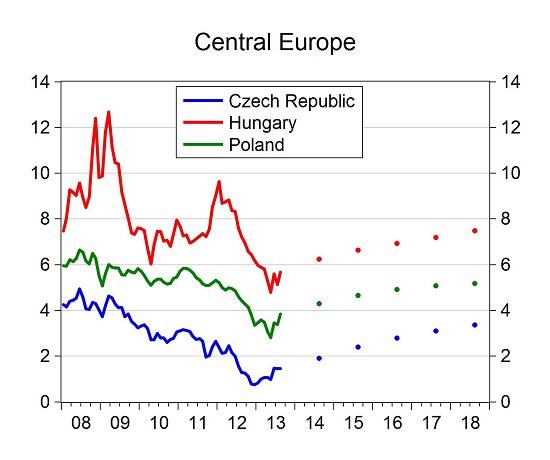

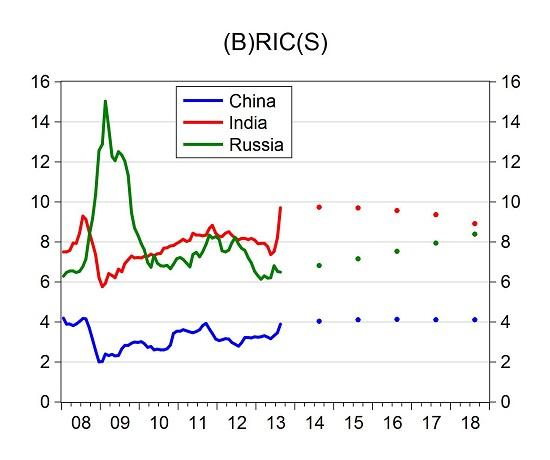

We calculated, using the expectation hypothesis of the term structure (EHTS), the expected 5-year maturity yields in a number of countries up to 2018. For example, under certain conditions, arbitrage should ensure that the current 6-year yield is the weighted average of the current 1-year yield and the expected 5-year yield one year from now; the current 7-year yield is the weighted average of the current 2-year yield and the expected 5-year yield two years from now, and so on.

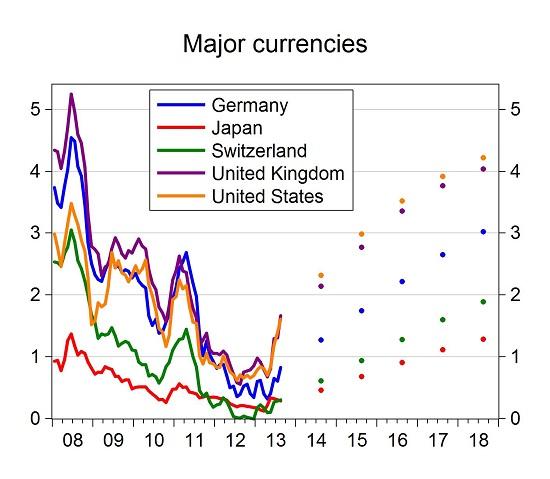

Figure 1 below shows that in the US and UK, the 5-year yield is expected to increase to slightly over 4 percent by 2018, to 3 percent in Germany, while in Switzerland and Japan yields are expected to stay below 2 percent.

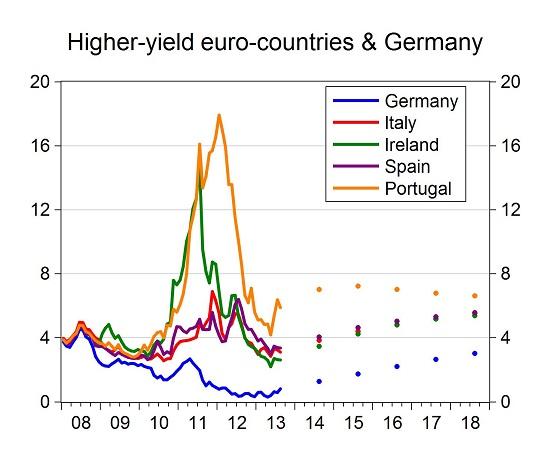

Among euro-area members, quite interestingly, the yields on Irish, Italian and Spanish 5-year government bonds are expected to converge at about 5.5 percent in 2018.

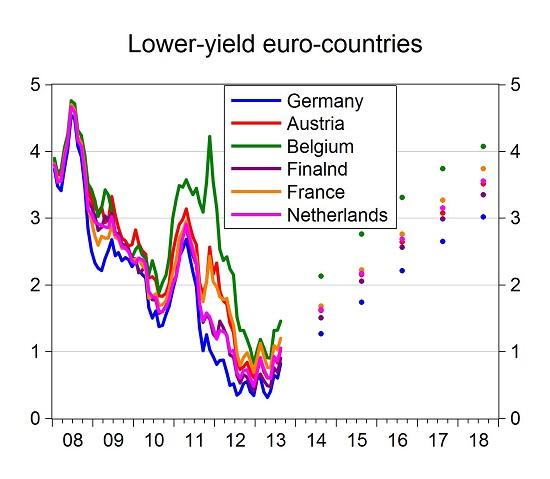

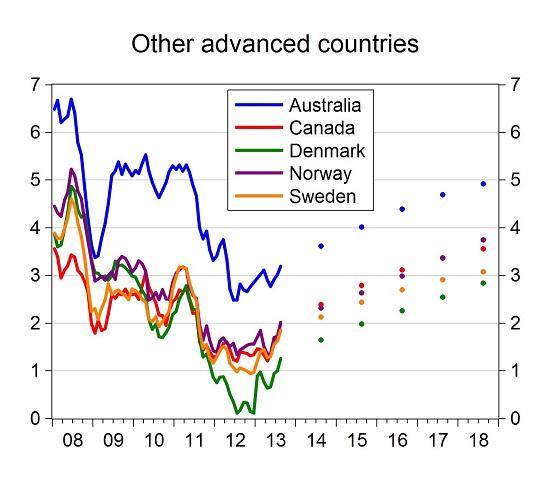

The panels of Figure 1 below show expectations for a number of additional advanced and emerging countries.

How much should we worry about the increase in yields? Certainly, any soaring of yields increases the cost of servicing the debt. Private sector yields will likely follow government bond yields.

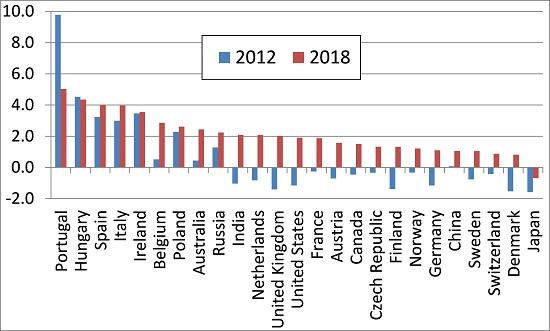

But one has to recognise that yields were very low recently: as Figure 2 indicates, more than half of the countries benefited from negative real interest rates on 5-year government bonds in 2012 (measures as the 2012 yield deflated with the IMF’s CPI inflation forecast for 2013-17). By 2018, all countries but Japan are expected to face a positive real interest rate (measured as the expected yield for 2018 deflated with the IMF’s CPI inflation forecast for 2018).

The expected 2018 real rates are about one to two percent per year for most countries, which is not far from the historical average for advanced countries. In this sense, the situation will only normalise in most of the countries. Also, since real GDP growth may be around 1-2 percent per year in a number of advanced countries, public debt sustainability should not be that difficult.

But with an expected real interest rate of about four percent, the situation is rather different in the four higher-yielding euro-area countries, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Ireland, plus in Hungary too. This real interest rate seems quite high, especially in light of the not too bright growth outlooks and the large stocks of public debts. Houston, we have a problem!

Figure 1: Five-year government bond yield (January 2008 – 19 August 2013) and the expected five-year yield (August 2014 – August 2018)

Notes. Solid line: Monthly average yields for January 2008 – July 2013 and the 19 August 2013 yield for August 2013. Dots: expected future yields for 2014-18, calculated on the basis of the expectation hypothesis of the term structure (EHTS), using the yield curve of 19 August 2013. The source of the underlying data is Datastream.

Figure 2: Real interest rates in 2012 and 2018 (percent per year)

Notes. 2012: 5-year government bond yield deflated with the average over 2013-17 of the IMF’s CPI inflation forecast. 2018: expected 5-year government bond yield for 2018 on 19 August 2013 deflated with the IMF’s CPI inflation forecast for 2018 (forecasts further ahead are not available). Thereby, we assume that the IMF’s inflation forecast for 2018 is the best expectation for each year during 2019-23. Countries are ordered according to their expected real interest rate in 2018.