A year since Cyprus

It is still too early to conclude that the Cyprus programme will be successful, particularly in terms of enabling the country to regain market access

A year ago EU and Cypriot officials were in tense negotiations trying to find the right balance between bailing-in and bailing-out Cyprus; ultimately, only uninsured depositors were bailed-in meaning that the major blunder of breaching the EU deposit insurance scheme could be avoided (thanks to the rejection of the plan by the Cypriot House of Representatives), that the Cypriot government was bailed-out with the programme’s approval and contagion was prevented. But despite our (and other economists) strong criticisms, capital controls were imposed for the first time in a euro-area member state, creating a de-facto second-league euro.

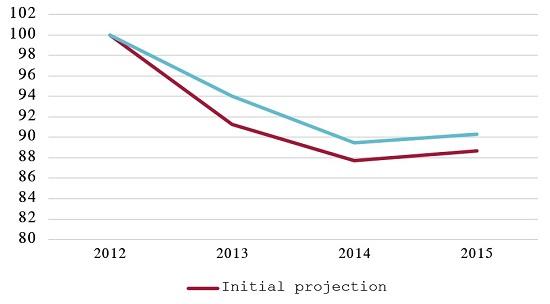

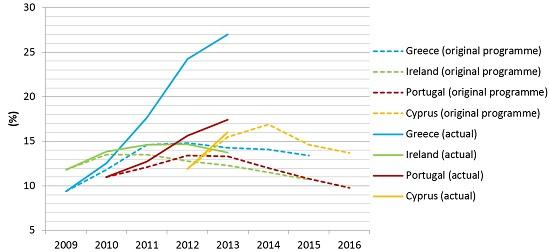

So far the programme has turned out slightly better than expected in terms of GDP growth; the latest European Commission economic forecast estimates that the Cypriot economy shrank by 6 percent during 2013 instead of the originally expected 8.7 percent; the economy will start growing again in 2015 as originally foreseen. However, as was the case in all other euro-area macroeconomic adjustment programmes, the unemployment rate overshot the forecast but only by one percentage point, increasing to 16 percent during 2013.

Cyprus real GDP (2012=100)

Sources: The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus, Occasional Papers 149, May 2013 and European Commission Economic Forecast Winter 2014

Unemployment rate projections and realisations in euro-area financial assistance programmes

Sources: IMF WEO October 2013, programme documents and European Commission Economic Forecast Winter 2014

The financial system reforms, which are probably the most important part of the programme because the banking sector was the root of the Cypriot crisis, are broadly on track although with some delays. Fitch Ratings have upgraded the ratings of Bank of Cyprus and Hellenic Bank, the two largest credit institutions on the island, because they were successfully recapitalised. In the case of Bank of Cyprus, this was done even without relying on state aid, while Hellenic Bank is still being restructured. The restructuring of the cooperative banking sector is also ongoing. This entails the merging of 93 cooperative credit institutions into 18 institutions under the management of the Central Cooperative Bank (under state control). Nevertheless, some substantial risks remain as non-performing loans continue to soar.

The progress made on the financial system has allowed the planned relaxation of the restrictive measures on capital movement to take place, and the capital controls are now expected to be completely abolished by the end of year according to Cyprus' Central Bank chief Panicos Demetriades, confirmed by Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades. As we argued in our latest assessments of the Troika programmes: in a monetary union, the lifting of capital controls is in principle easier to achieve, because the common central bank can stand ready to replace out-flowing liquidity. However, solvency problems in the banking system need to be addressed first so that the European Central Bank can step in.

It is still too early to conclude that the Cyprus programme will be successful, particularly in terms of enabling the country to regain market access in a timely manner for a clean exit. But it can be said that so far so good: the programme is broadly on track with respect to conditionality compliance and the macroeconomic outcomes have been better than expected, with the exception of the labour market. Thus, the likelihood of Cyprus turning out to be a second Ireland is greater than that of it turning into a second Greece or even Portugal.