Will European Union countries be able to absorb and spend well the bloc’s recovery funding?

To help finance the post-coronavirus recovery, the European Union is raising large amounts to pass on to its members. But absorption of EU funds is ty

The European Union’s landmark recovery instrument, Next Generation EU (NGEU), will be embedded into the EU’s budget. This makes sense, because the EU budget is a well-established framework and hence can be deployed readily. But pay-outs from the EU budget are disbursed slowly to member states, partly because programmes have to be designed, approved and implemented, and must also pass various checks to ensure the proper use of EU funds.

EU budgets include two types of numbers: ‘commitment appropriations’, which are ceilings on spending promises, and ‘payment appropriations’, which are ceilings on possible payments. Actual payments from the EU budget are typically less than payment appropriations, because not all beneficiaries are able to use the available funds. EU funding is considered to have been absorbed when money is paid out by the Commission to an EU country. Such payments include advances, interim and final payments.

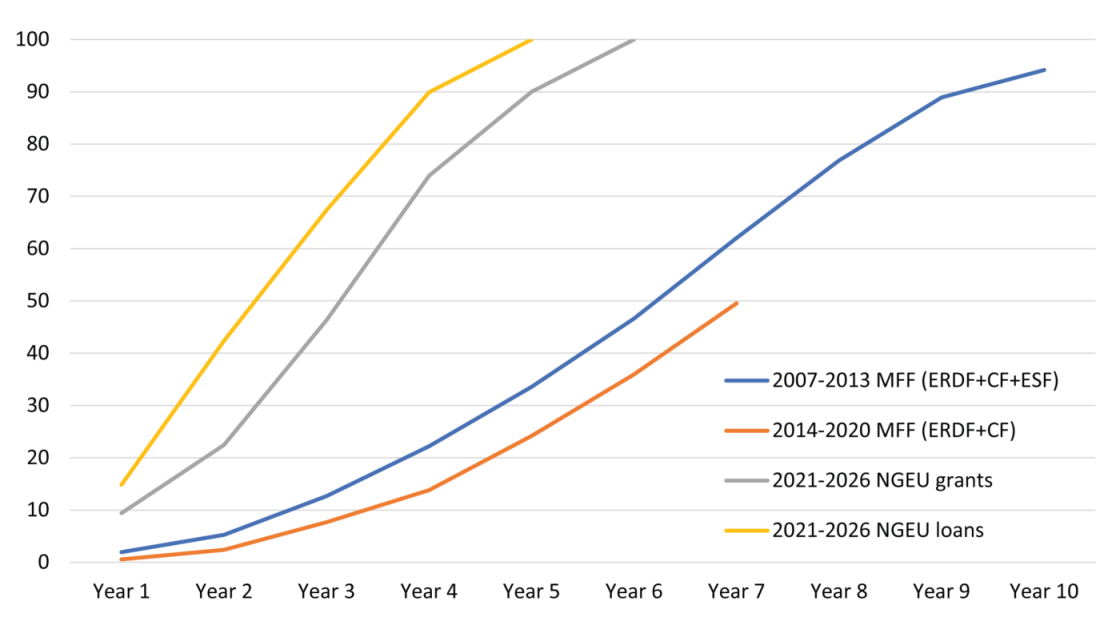

Of the recovery money, the European Commission expects only a quarter to be paid out in 2021-2022, while three-quarters will be paid out in 2023 and after. Even this rather slow expected speed of NGEU disbursement would be rapid compared to the record of absorption of EU Structural Funds (Figure 1). This puts a question mark over whether the NGEU money can really be paid out as planned.

Figure 1: Historical EU structural fund pay-out rates and assumed pay-out rates from NGEU (%)

Source: Bruegel[i]. Note: Year 1 is the first year of the respective programme, ie 2007 for the 2007-2013 MFF, 2014 for the 2014-2020 MFF, and 2021 for NGEU. MFF: Multiannual Financial Framework; CF: Cohesion Fund; ERDF: European Regional Development Fund; ESF: European Social Fund. The pay-out rate (or in other words, the ‘absorption rate’) is the percentage of the total amount committed in the EU budget to a member state that has been paid by the Commission to that member state.

Italy and Spain, the two largest expected beneficiaries of the NGEU in terms of euro amounts, are among the worst performers in terms of absorption of EU funds. For the 2014-2020 period, Spain had absorbed only 39% of the money it was due from European Structural Investment Funds (ESIFs) by 23 September 2020 – the EU’s worst rate – while Italy at 40% is also among the slowest. Croatia was similarly a poor performer with a 2014-2020 ESIF absorption rate of just 39% (by 23 September 2020), yet Croatia is expected to receive grants from NGEU equivalent to more than 10% of its GDP, with potentially another 6.8% as loans.

For the new EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) period starting in January 2021, countries will have to absorb:

(a) The remaining portions of the 2014-2020 MFF funds, which are rather large for many countries;

(b) The ‘standard’ seven-year 2020-2027 MFF funds; and

(c) The funds available under NGEU.

Altogether, the amount of EU money to be absorbed from January 2021 will be several factors greater than earlier amounts. Absorbing all these EU funds might prove to be an immense challenge.

Will NGEU programme design help absorption? For the largest component of NGEU, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), countries will have to prepare reform and investment proposals in their national recovery and resilience plans, which will be assessed by the European Commission and approved by the Council. The July 2020 European Council set the following principles for assessment: “The criteria of consistency with the country-specific recommendations, as well as strengthening the growth potential, job creation and economic and social resilience of the Member State shall need the highest score of the assessment [sic]. Effective contribution to the green and digital transition shall also be a prerequisite for a positive assessment.”

Country-specific recommendations (CSRs) are made in the context of the European Semester, the EU’s annual economic policy coordination mechanism. The implementation rates of CSRs have been rather poor and hence, at first sight, one might conclude that linking NGEU to CSRs will pose additional challenges. But in fact, the link provides great freedom to member states, because the 2020 CSRs, quite naturally, ask member states to address the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis, which they are doing anyway. For example, Italy received four CSRs:

1) Address the pandemic, sustain the economy and support the ensuing recovery; later, when economic conditions allow, ensure public debt sustainability;

2) Provide income replacement, social protection, preserve jobs;

3) Provide liquidity to the real economy, promote public and private investment (here some concrete green and digital areas are listed: energy, research and innovation, sustainable public transport, waste and water management, digital infrastructure);

4) Improve the efficiency of the judicial system and the effectiveness of public administration.

The first three CSRs for Spain are almost identical to those for Italy, while the fourth recommends improved coordination between different levels of government and strengthening of the public procurement framework.

The freedom EU countries have in designing national recovery and resilience plans might foster faster absorption of NGEU funds, since countries should know the investment areas where they can make the fastest progress. Will this freedom be enough to overcome the hurdles to EU fund absorption?

Slow implementation and low absorption capacity are major problems, yet absorption of EU funds cannot be an objective in itself. As a 2018 special report of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) highlighted, the rush to absorb funds can lead to insufficient consideration of value for money. ECA argued that the actions taken by the Commission and member states to tackle slow absorption of the 2007-2013 funds “focussed mainly on absorption and legality, but did not take due account of performance considerations” (paragraph 87). This makes designing a strong governance framework for NGEU even more important, in order to ensure that the money is well spent.

Annex

Table 1: Pay-out rates of the 2007-2013 ERDF, CF and ESF

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Greece | 2.0 | 5.0 | 10.6 | 21.9 | 34.9 | 49.2 | 69.6 | 88.3 | 98.1 | 100.0 |

| United Kingdom | 2.0 | 5.0 | 13.6 | 27.8 | 38.9 | 51.0 | 56.8 | 73.1 | 88.0 | 95.0 |

| Bulgaria | 2.2 | 5.6 | 9.6 | 15.7 | 23.8 | 36.6 | 50.1 | 66.2 | 85.2 | 95.0 |

| Austria | 2.1 | 5.2 | 19.3 | 29.4 | 40.3 | 53.7 | 69.0 | 80.3 | 93.2 | 95.0 |

| Portugal | 2.0 | 5.0 | 13.0 | 25.2 | 37.8 | 59.2 | 78.7 | 92.6 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Finland | 2.0 | 5.0 | 16.5 | 25.8 | 40.9 | 54.7 | 75.7 | 89.2 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Ireland | 2.0 | 11.1 | 23.3 | 36.2 | 48.3 | 60.3 | 70.1 | 79.7 | 90.0 | 95.0 |

| Sweden | 2.0 | 5.0 | 16.2 | 26.9 | 46.5 | 53.3 | 68.7 | 89.9 | 94.7 | 95.0 |

| Denmark | 2.0 | 5.0 | 11.5 | 19.7 | 38.3 | 45.3 | 54.4 | 80.8 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Estonia | 2.2 | 5.5 | 19.5 | 35.0 | 42.0 | 61.3 | 81.3 | 92.3 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Latvia | 2.2 | 5.5 | 14.9 | 25.1 | 36.4 | 52.2 | 66.0 | 81.7 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Lithuania | 2.2 | 5.5 | 21.3 | 34.1 | 48.0 | 62.9 | 78.8 | 93.7 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Luxembourg | 1.0 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 16.1 | 40.6 | 51.8 | 67.8 | 83.8 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| Slovenia | 2.2 | 5.5 | 13.5 | 24.8 | 37.0 | 50.3 | 62.9 | 81.7 | 95.0 | 95.0 |

| France | 1.6 | 5.0 | 13.6 | 23.6 | 34.5 | 43.0 | 60.0 | 76.3 | 92.1 | 95.0 |

| Netherlands | 2.0 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 17.4 | 33.6 | 45.6 | 63.9 | 80.6 | 91.2 | 95.0 |

| Poland | 2.1 | 5.4 | 13.0 | 23.2 | 37.2 | 52.3 | 67.9 | 85.3 | 94.9 | 95.0 |

| Slovakia | 2.2 | 5.5 | 10.0 | 18.9 | 27.8 | 41.1 | 52.7 | 60.1 | 85.3 | 95.0 |

| Cyprus | 2.2 | 5.5 | 15.2 | 26.2 | 37.4 | 44.3 | 61.3 | 84.3 | 91.9 | 95.0 |

| Belgium | 1.7 | 5.0 | 18.1 | 23.2 | 32.2 | 49.2 | 68.9 | 82.5 | 93.1 | 94.7 |

| Germany | 2.0 | 5.2 | 17.5 | 28.6 | 41.2 | 54.1 | 70.8 | 83.3 | 92.5 | 94.6 |

| EU28 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 12.7 | 22.2 | 33.6 | 46.6 | 62.0 | 76.9 | 88.9 | 94.1 |

| Hungary | 2.2 | 5.6 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 35.0 | 43.9 | 59.0 | 76.1 | 88.4 | 94.0 |

| Czechia | 1.4 | 5.6 | 12.3 | 20.4 | 26.9 | 38.9 | 52.6 | 63.8 | 84.5 | 94.0 |

| Italy | 1.7 | 5.0 | 9.8 | 15.0 | 21.7 | 30.8 | 50.1 | 63.4 | 79.4 | 91.3 |

| Spain | 2.0 | 5.0 | 10.7 | 22.5 | 36.7 | 51.9 | 62.9 | 73.0 | 84.1 | 91.2 |

| Romania | 2.2 | 5.6 | 10.5 | 13.2 | 16.9 | 23.0 | 38.3 | 57.1 | 70.9 | 90.4 |

| Malta | 2.2 | 5.5 | 9.7 | 17.6 | 27.3 | 37.2 | 50.3 | 73.4 | 81.6 | 89.0 |

| Croatia | 0.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 10.3 | 18.3 | 45.1 | 58.6 | 80.7 |

Source: Bruegel based on the Commission’s ‘SF 2007-2013 Funds Absorption Rate’ dataset (which includes the ERDF, CF and ESF). Yet the implied maximum available funds for 2007-2013 was cut back by more than 4% from 2015 to 2016, so I adjusted the 2016 absorption rate included in the dataset to eliminate this retrospective cutback. Note: CF: Cohesion Fund; ERDF: European Regional Development Fund; ESF: European Social Fund.

Table 2: Pay-out rates of the 2014-2020 ERDF and CF

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Lithuania | 0.9 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 16.6 | 30.0 | 36.9 | 66.9 |

| Estonia | 0.9 | 2.3 | 10.9 | 19.7 | 32.1 | 46.5 | 61.9 |

| Greece | 0.6 | 6.1 | 16.1 | 23.2 | 29.5 | 39.0 | 60.0 |

| Sweden | 0.7 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 19.5 | 35.6 | 43.5 | 59.9 |

| Finland | 0.9 | 1.9 | 11.9 | 22.6 | 36.7 | 49.3 | 59.6 |

| Hungary | 1.9 | 7.9 | 19.1 | 33.8 | 43.6 | 59.2 | |

| Portugal | 0.6 | 2.4 | 9.1 | 19.1 | 31.1 | 44.1 | 57.6 |

| Poland | 0.3 | 1.9 | 8.6 | 15.3 | 28.5 | 42.8 | 57.6 |

| Latvia | 0.9 | 1.9 | 8.5 | 12.6 | 20.4 | 37.3 | 55.7 |

| Czechia | 1.9 | 5.0 | 12.5 | 22.2 | 37.4 | 54.4 | |

| Luxembourg | 0.9 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 13.4 | 36.1 | 40.0 | 54.3 |

| Slovenia | 0.0 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 11.3 | 18.8 | 35.5 | 52.9 |

| Cyprus | 1.4 | 2.8 | 6.1 | 20.7 | 39.7 | 47.2 | 51.8 |

| EU28 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 7.7 | 13.8 | 24.2 | 35.9 | 49.5 |

| Bulgaria | 0.0 | 1.9 | 8.4 | 15.2 | 23.4 | 33.5 | 48.9 |

| Denmark | 0.9 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 14.1 | 22.9 | 34.9 | 48.4 |

| Malta | 0.9 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 12.5 | 20.4 | 33.9 | 47.0 |

| Interreg | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 8.3 | 16.4 | 29.4 | 45.0 |

| United Kingdom | 0.9 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 10.5 | 22.4 | 31.5 | 42.0 |

| France | 0.6 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 12.1 | 21.3 | 32.7 | 41.3 |

| Belgium | 0.8 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 9.0 | 16.6 | 32.0 | 40.6 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 20.8 | 32.4 | 40.6 |

| Austria | 0.9 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 11.5 | 20.0 | 35.4 | 39.4 |

| Romania | 0.0 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 12.3 | 19.0 | 29.0 | 39.3 |

| Slovakia | 0.8 | 1.9 | 7.4 | 12.2 | 22.3 | 29.5 | 39.2 |

| Ireland | 1.4 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 10.9 | 23.9 | 29.9 | 38.6 |

| Croatia | 0.9 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 25.7 | 38.6 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 16.6 | 26.0 | 38.5 |

| Netherlands | 0.9 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 10.9 | 21.1 | 31.3 | 37.8 |

| Spain | 1.4 | 5.9 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 19.8 | 28.8 | 35.3 |

Source: Bruegel based on the Commission’s ‘Regional Policy 2014-2020 EU Payment Details by EU Countries’ dataset (which includes the ERDF and CF only). The approximate the expected pay-out rate end-2020, I assumed that the average daily pay-out amounts in 1 January – 11 September 2020 will be made on average in 12 September – 31 December 2020. Note: CF: Cohesion Fund; ERDF: European Regional Development Fund.

[i] Sources for Figure 1 in detail: absorption rates for the 2007-2013 MFF are from the Commission’s ‘SF 2007-2013 Funds Absorption Rate’ dataset (which includes the European Regional Development Fund, Cohesion Fund and European Social Fund). The implied maximum available funds for 2007-2013 was cut back by more than 4% from 2015 to 2016, so I adjusted the 2016 absorption rate included in the dataset to eliminate this retrospective cutback. The 2014-2020 pay-out rates are based on the Commission’s ‘Regional Policy 2014-2020 EU Payment Details by EU Countries’ dataset (which includes the ERDF and CF only). To approximate the expected pay-out rate end-2020, I assumed that the average daily pay-out amounts from 1 January to 11 September 2020 will be made on average from 12 September to 31 December 2020. The expected annual pay-out speed of NGEU is from the 28 May 2020 European Commission proposal, adjusted by the modifications approved by the 21 July 2020 European Council, which set the pre-financing for the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the largest component of NGEU, at 10% in 2021, required that all NGEU-related payments will have to be made by 31 December 2026, and changed the available amounts of all instruments of NGEU compared to the Commission’s initial proposal.

Recommended citation:

Darvas, Z. (2020) 'Will European Union countries be able to absorb and spend well the bloc’s recovery funding?' Bruegel Blog, 24 September