Whose (fiscal) debt is it anyway?

The authors map how much fiscal debt is in the hands of domestic and foreign holders in the euro area. While the market for debt was much more interna

Figure 1 depicts the evolution of euro-area general government debt and whether it is in domestic or foreign hands. The investor base varies significantly across countries, but we do observe general trends that inform our understanding in this respect.

Between 1995 and 2007, financial integration in the euro area led to a diversification of the investor base. The share of resident investors (and in particular domestic banks) dropped from 72% and 35% to 48% and 25% respectively, during a period in which outstanding debt as a share of GDP generally declined.

During the crisis, however, this trend reversed, as foreign investors withdrew cross-border holdings and domestic banks increased their exposure, in particular in countries that were hit hardest by the sovereign-debt crisis.

As a consequence, domestic investors now hold more sovereign debt, in absolute and relative terms, than in 2007. However, what is also true is that there is a partial shift within the domestic investor base, from banks to the central banks. Indeed, domestic central banks bought a significant share of sovereign bonds (mainly from foreign investors) within the scope of the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) programme.

The ownership structure of national debt is extensively discussed in the light of cross-border risk sharing within a monetary union like the euro area. Economic research highlights that regional shocks can be partly absorbed by cross-holdings of assets. Indeed, risk sharing is most effective if both debt and equity markets are well integrated (e.g. Asdrubali et al, 1996).

Furthermore, greater domestic ownership of public debt is associated with relatively higher longer-term yields. A higher demand by foreign investors implies lower long-term yields on debt. However, the direction of causality is not clear: low yields could attract international investors, while increased international demand could reduce borrowing costs.

At the same time there are risks associated with a home bias of investors as it creates a dangerous link between financial institutions and national fiscal policy which can amplify shocks. However, in times of stress, a home bias in ownerships acts as a cushion. Foreign owners of domestic debt are quicker to sell it, increasing both refinancing costs (see here and here) for the country, as well as the threat of sudden stops. Relying on domestic ownership can act as a stabilising force.

Borrowing Cost

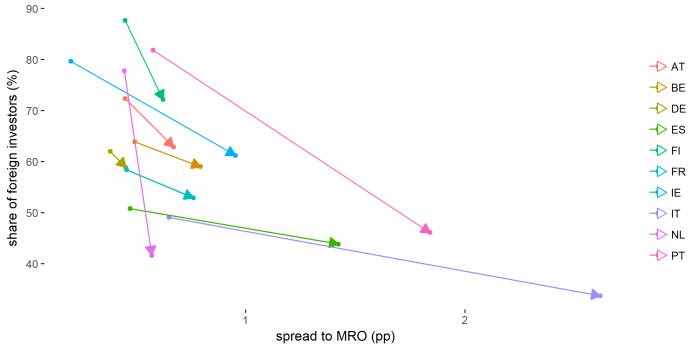

Figure 2 demonstrates how the negative relation between a higher share of foreign investors and the refinancing costs have played out in the EU since 2007. The reduction in the share of foreign investors between 2007 and 2018 went hand-in-hand with an increase in the spread to the ECB’s main refinancing rate (MRO) (the spread to the MRO is defined as the difference between a country’s annual average 10-year bond yield and the annual average MRO rate). A notable exception in this graph is the Netherlands, which witnessed a substantial decrease in the share of foreign investors but with a marginal increase in the spread.

Figure [2]: Pre-crisis vs current situation: foreign investors’ sovereign bond holdings and spread to MRO (start: 2007 end: 2018)

Source: Bloomberg, Arslanalp and Tsuda (2012)

Note: The spread to the MRO is defined as the difference between a country’s annual average 10-year bond yield and the annual average MRO rate.

On the other hand, the ECB’s QE programme has tied up a significant share of total sovereign bonds in national central banks’ balance sheets, which limits supply on the secondary market. Research has found that this has lowered yields and therefore, muted the increase in yields caused by lower foreign demand (e.g. Krishnamurthy, Nagel, and Vissing-Jorgensen, 2018 and Ghysels et al. 2017).

Has the doom-loop weakened?

Figure 3 shows the evolution of banks’ exposure to domestic and other euro-area sovereign debt since 2007. We observe that for most countries (except Belgium, France and Greece), banks own more of their own sovereign bonds as a share of total assets than they did prior to the crisis. However, this trend has reversed since 2014 for all countries shown, except Greece, Italy and Portugal.

There is a mixed picture when it comes to how much sovereign debt issued by other euro-area countries is held by banks. Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain have seen a clear increase, but for the rest there is probably a small decline – especially since 2014.

While there is arguably a general tendency to hold small and declining shares of any sovereign debt (after all, the numbers in Figure 3 are well below 10% for most), the home bias remains a prime characteristic of banks’ balance sheets.

There is more fiscal debt today than there was before the crisis, and in most cases more even than there was in the mid-90s. And it continues to lie mostly in the hands of domestic investors with the central bank becoming a sizable owner following QE. On the one hand, this is a reflection of the fragmented fiscal quality of the sovereigns in economic and monetary union, and does not help correct the doom loop that proved so destructive during the fiscal crisis. Although the increased home bias insulates countries from affecting each other through the banking system, it implies a thoroughly incomplete monetary union.