What Single Market?

“The commitment to complete the Digital Single Market by 2015 has to be delivered on: today's market fragmentation hampers the release of the dig

“The commitment to complete the Digital Single Market by 2015 has to be delivered on: today's market fragmentation hampers the release of the digital economy's full potential.” European Council ‘Conclusions’, 25th October 2013 (EUCO 169/13).

The most recent European Council summit contained a number of pronouncements on the problems facing Europe’s digital economy and few were mentioned as frequently as market fragmentation[1]. Telecoms has long been recognised as among the most problematic sectors in the EU single market; for example, internet service provision repeatedly ranks as the most-complained-about market in the Commission’s Market Monitoring Survey. While current internet penetration and access speeds in much of Europe are first rate, the rollout of next-generation access networks (NGAs) has been slow and questions have repeatedly been asked about the level of investment pursued by incumbent European internet service providers (ISPs). Recent regulatory efforts, such as the Commission’s ‘Connected Continent’ package, have been criticised as insufficient to foster the necessary steps towards a true single telecoms market.

ISPs, as an archetypal network industry, benefit from economies of scale. A real single market in internet access would enable European, rather than national, firms to operate at a scale and efficiency unattainable by nationally-bound companies. But while the lack of such European companies and enduring market fragmentation is repeatedly cited, there is a striking absence of empirical evidence to quantify the problem. Through the novel application of a large, open data set we can provide a sense of the scale of market fragmentation and how far from a single market the EU remains in a key market of the telecoms sector.

Our focus is restricted entirely to public fixed internet access lines – that is, business internet and mobile data connections are omitted. This is for two reasons. First, because business connections are weak substitutes for home connections (the clue is in the name) and we are trying to focus on one market. The second, omission of mobile connections, requires more justification. While much is currently being written about the future dominance of mobile data, many of these claims remain conjectural rather than justified. For example, despite the explosion of data being routed through portable devices, over 70% of it is ‘offloaded’ through fixed connections[2] – primarily with the use of Wi-Fi connected to a fixed line. We may be browsing more on mobile devices, but the substantial majority of that mobile data traffic remains ultimately tied to fixed connections. It may well be the case that such connections lose their prominence in the long-term, but rumours of their imminent demise are still overstated. As such, we chose to consider mobile and fixed connections as separable markets, and concentrated on fixed lines due to their continued dominance in overall traffic carriage.

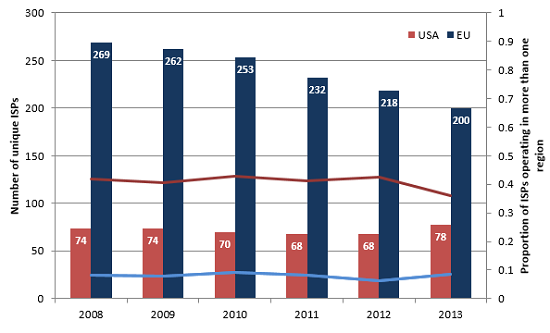

We use the USA as our baseline case of a unified single market, and compare the instances of inter-state ISPs in America to inter-country ISPs in the EU. There are some clear reasons to expect differences when we use the comparison of EU states and US states – among them historical, linguistic and cultural – but while we understand the limitations of the exercise, the comparison remains heuristically useful. Using the dataset we derive a list of ‘significant’ ISPs[3] in each US state, and each EU country, on an annual basis from 2008-2013. Then, by detecting duplicates of the same ISP across multiple states or countries, we can find every instance of ISPs providing service across more than one market. Below, we plot on the left axis the number of unique ISPs, detected through the dataset, operating in the US (red) and in the EU (blue). On the right axis, we plot the proportion of ISPs which operate in more than one market (i.e. more than one American state, red line, or more than one European country, blue line).

Figure 1. Comparing unique ISPs

Source: Bruegel calculations based on NetIndex data

Four points are striking:

- The EU market appears to contain well over double the number of unique ‘significant’ ISPs compared to the US market.

- There is some evidence of consolidation in the EU market over the past five years but none in the US.

- A far greater proportion of American ISPs operate in more than one state compared to EU ISPs operating in more than one country: roughly 40% of US ISPs versus fewer than 10% of EU ISPs. These proportions have been stable over time.

- Combining (2) and (3), since the EU consolidation has not impacted on the proportion of cross-border ISPs, this EU consolidation appears an overwhelmingly national phenomenon.

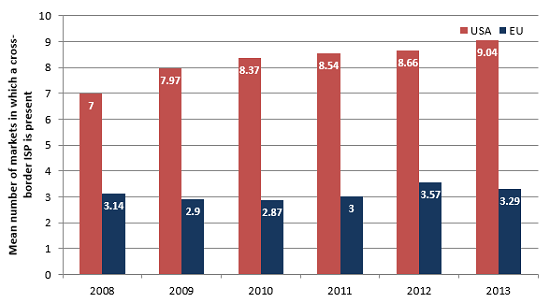

Next, we can compare the depth of market integration by comparing the average number of markets in which a cross-border ISP is present across the US and EU.

Figure 2. Comparing the depth of cross-border ISPs

Source: Bruegel calculations based on NetIndex data

Based on this, it appears that American cross-border entry has been increasing robustly over the last five years – in 2008 ISPs with operations in more than one state had operations in seven on average, while this year they are present in over nine on average. There is no apparent trend in the EU’s case; cross-border ISPs have not been increasing their geographic presence.

While these metrics say nothing about the downstream effects of fragmentation on quality, they provide a strong indication of how far EU telecoms lags behind a benchmark single market. Fewer than 10% of European ISPs provide a service in more than one country, those that do provide a service to just around three countries, and while there is some evidence of market consolidation, this is evidently an overwhelmingly national phenomenon. That none of these indicators (apart from overall number of ISPs) have substantially shifted over the last five years ought to be a justified cause for the concern of regulators.

[1] Research assistance from Michele Peruzzi and Giuseppe Daluiso is gratefully acknowledged.

[2] See European Commission (2013) Study on impact of traffic off-loading and related technological trends on the demand for wireless broadband spectrum, available here.

[3] The NetIndex dataset we use here is generated by website visits to speedtest.net, where individuals can test the speed of their internet connections. Each speed test logs the country, region and ISP details of the consumer and data is aggregated at the ISP and regional level on a monthly basis. Using this, we can observe how many tests were run from a given ISP/region combination in a given month. This provides a rough proxy for the market share of different ISPs: more subscribers will be associated with more tests. It is imperfect since the sample is self-selecting – however, this bias should not affect the results above: we aggregated the total number of tests done in a given EU country/US state in a given year, then computed the ‘test share’ for each ISP. Many ISPs are reported which are niche, business or private networks, and so we only included those ISPs with a ‘test share’ greater than 1% of their market – these are our ‘significant’ ISPs. So an ISP with a test share of 2% in Idaho in 2009 was included, while one with a share of 0.7% in Portugal wasn’t.

It should be clear that some non-public networks could be included, while other public ISPs could have been omitted. However, all the major ISPs should comfortably be expected to surpass this threshold. We removed all ISPs which were evidently non-public or mobile (e.g. their names included ‘Business Internet’ or similar). Such a process is imperfect, however, and so the numbers presented should be interpreted as highly illustrative rather than wholly exact.