US tariffs and China's holding of Treasuries

China has the biggest bilateral trade surplus vis-à-vis the US but is also a top holder of US government bonds. While China has started to counteract

The recently published Reuters’ article on the current situation between the US and China holds some interesting quotes. Answering a reporter, Zhu Guangyao - Chinese Vice Finance Minister - reportedly reiterated China’s policy regarding its foreign exchange reserves, saying it is a responsible investor and that it will safeguard their value. Jeffrey Gundlach, chief executive of DoubleLine Capital LP, believes that China can use its Treasury holdings as leverage, but only if they keep holding them. Jeff Klingelhofer, portfolio manager at Thornburg Investment Management Inc., anticipated that if China committed to dumping Treasuries, it would have an immediate and temporary impact on money markets in the United States; however, it would be a bigger hit to the sustainability of what they are trying to accomplish. Brad Setser, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, said China can sell Treasuries and buy lower-yielding European or Japanese debt.

Source: Reuters

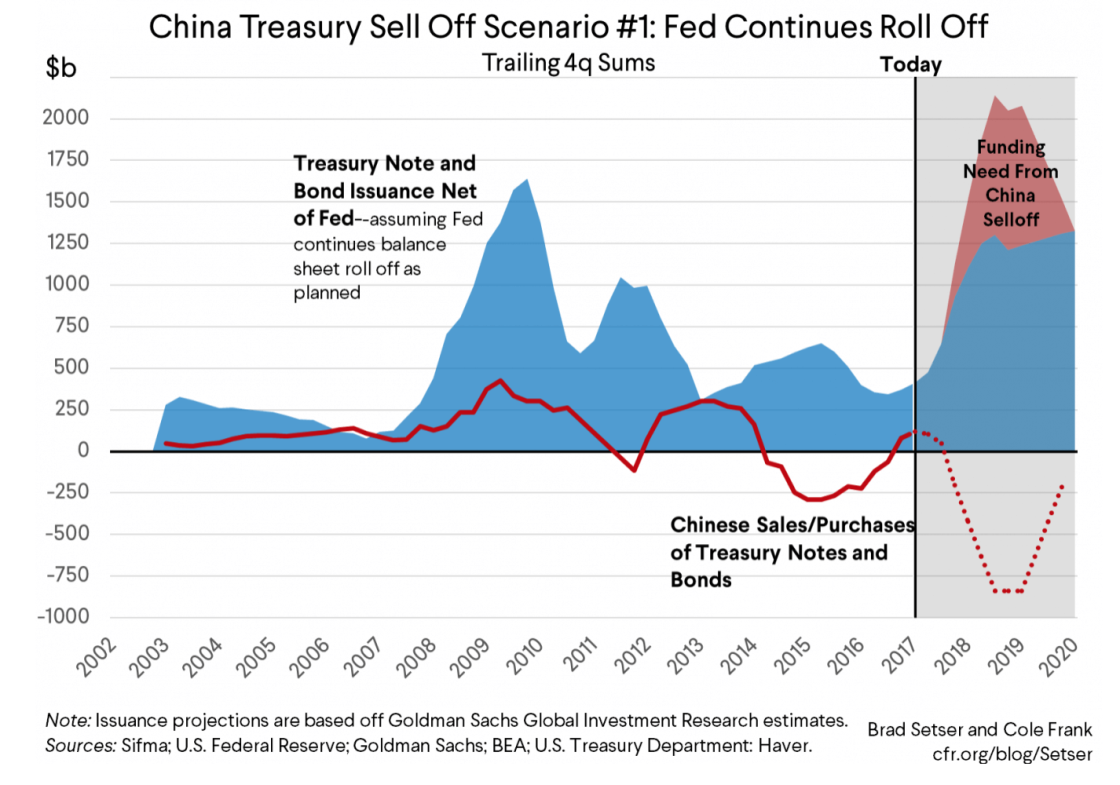

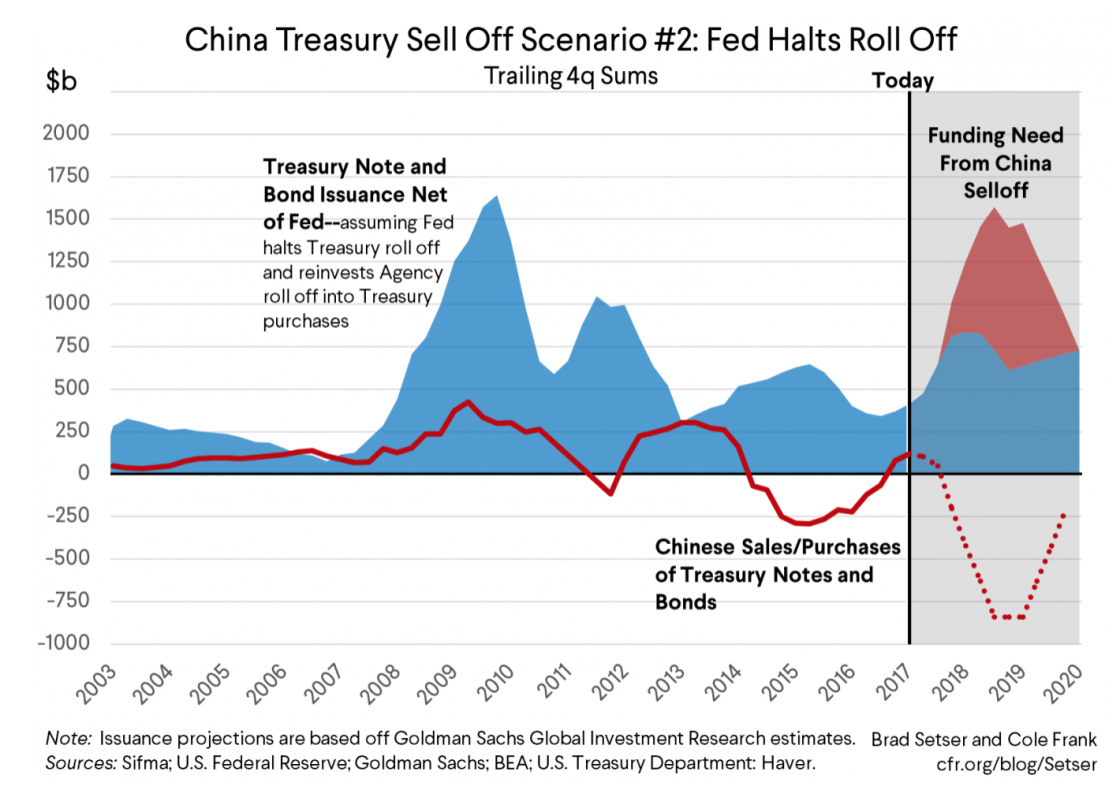

Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relationship has been watching developments in China’s external portfolio for a long time. He also of estimates what would happen if China started selling off its Treasury portfolio. Selling the entire Treasury portfolio would generate about 6% of US GDP in sales, which could raise long-term interest rates by about 30 basis points. The impact would be larger in the short-run but then higher US rates - in relative terms to the to still low European rates - would pull private funds into the US fixed income market. If China’s sales are pushing up long-term rates and slowing the US economy, the Federal Reserve should logically slow the pace of rate hikes or scale back its “quantitative tightening”/ balance sheet roll off.

On the surface, it looks like the US is vulnerable: the stock of Treasuries that the market has to absorb to fund the rising US fiscal deficit is large, and if China started to sell, the amount of US paper that non-Chinese investors would need to absorb would be massive. However, Setser thinks China’s sales are in some ways easier to counter now, as the Federal Reserve can signal a slowdown of rate hikes and it can respond to Chinese sales by changing its pace of balance sheet roll off. On its side, the Treasury could start issuing more bills and fewer notes, offsetting the impact of China selling longer dated bonds and likely increasing its cash holdings. Furthermore, the Fed could raise the maturity of its holdings. Overall, Setser thinks that the US government should spend some time thinking about the impact of Chinese sales of assets other than Treasuries, because Treasuries sales, in a sense, are easy to counter.

Martin Sandbu thinks that Setser’s analysis is correct but not the end of the story. If China were to shift its holdings from low-paying bonds to higher-yielding assets or pursue a policy of not financing the US economy at all, then the American economy would need to pay more to finance its current account deficit or run down its international investment position. Such a dent in the American "exorbitant privilege" of guaranteed cheap external borrowing rates could easily be self-reinforcing in that others will demand a higher yield for holding US assets. If this leads to a fall in the dollar and a smaller deficit, then this could be sustained and might even be in line with what Trump sees as desirable. That being said, this government is not about to tighten its belt, so it would have to be the private sector doing so through less investment by companies or lower consumption for households.

Michael Pettis wrote a long post in which he argues that if China is threatening to retaliate against any US trade action by reducing its purchases of US government bonds, not only would this be a pretty hollow threat but, in fact, it would be exactly what Washington wants. Pettis looks at five ways in which Beijing can reduce official purchases of US government bonds. He argues that some of them would not change anything for either China or the US; others would change nothing for China but would cause the US trade deficit to decline either in ways that would reduce US unemployment or that would reduce US debt; and another still would cause the US trade deficit to decline in ways that would likely either reduce US unemployment or reduce US debt but also cause the Chinese trade surplus to decline in ways that would likely either increase Chinese unemployment or increase Chinese debt. Pettis’ conclusion is that by purchasing fewer US government bonds, Beijing would leave the US either unchanged or better off; however, doing so would leave China either unchanged or worse off.

Jeffrey Frankel has a broader post on why he thinks China will not yield in Trump’s trade war. In this piece, he highlights that the surplus country is often in a stronger position because it has accumulated financial claims against the other - in this case, well over a trillion dollars of Chinese official holdings of US treasury securities. It is true that if the Chinese government dumped US treasury securities, the fall in their price would hurt itself as well as the US. Nonetheless, this does not nullify the point. For one thing, China does not necessarily have to decide to sell them. As the US debt burgeons and US interest rates rise - two trends which are virtually certain to continue this year - trade conflict could produce rumors that the Chinese might stop buying US treasury securities which, in turn, could be enough to lower US bond prices and increase interest rates.

Steven Englander thinks it is possible that China will use talk of such steps to make the Trump administration more flexible. However, he believes it is very unlikely that Beijing can follow through because financial measures such as depreciating the yuan or selling off Treasuries do as much damage to China as to the US, and several of them do tremendous damage to China's neighbors and emerging-market countries that Beijing is courting in making the yuan an international currency.

US Treasury yields tend to lead Chinese yields, and an increase in US yields would spill over globally. The People's Bank of China could change domestic policy to offset this, but that would not insulate the rest of the emerging markets and even the developed world. Nor is the Chinese stock market insulated from Wall Street. The currency implications are uncertain: selling US Treasuries and buying European bonds or Japanese assets will probably weaken the dollar thus putting downward pressure on China's own currency. Emerging-market currencies would likely follow suit and decline against both the euro and the yen. If China went so far as to boycott US Treasury auctions, the dollar would fall sharply even as US yields climbed.

Neil Irwin writes that it would be a risky maneuver in which China could potentially have a lot to lose. Suddenly unloading some of its US debt holdings or even signaling an intention to buy fewer dollar assets in the future would probably cause long-term interest rates in the US to rise - at least temporarily. But it would also drive down the value of China’s existing bond portfolio- meaning that China could lose billions- and it would tend to push down the value of the dollar relative to other currencies, which would actually help the US attain more advantageous trade terms. Even after all that, bond prices would most likely re-adjust over time as other buyers take advantage of the rise in interest rates. In the medium term, the performance of the US economy and the actions of the Federal Reserve do more to determine bond prices than the decisions of a single buyer or seller, even as large as China.

Edward Harrison thinks that China cannot use its Treasury holdings as a leverage because, if the Chinese really wanted to use Treasury bonds as a weapon, they would need to either float their currency or revalue it. And that, according to Harrison, is not at all what they want to do since revaluation would reduce Chinese exports and slow economic growth. He expects the ongoing trade conflict to escalate and for people to misdiagnose the constraints as well - with the result that misdiagnoses will ultimately increase the conflicts and not diminish them.